ORTHOPAEDICS

Atypical femur shaft biphosphonate fractures

A case of atypical periprosthetic subtrochanteric femur fractures during bisphospohonates therapy

July 13, 2016

-

Bisphosphonates are used to treat postmenopausal and glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis, Paget’s disease of bone and malignant hypocalcaemia. They have been related to the atypical femur shaft fracture.

We present a case of an 83-year-old woman on long term bisphosphonates presenting with atypical femur shaft fracture. She underwent surgery for this and after a few months she presented with the same fracture non-union as periprosthetic fracture. She was treated with another surgery and discontinuation of bisphosphonates.

Purpose and clinical relevance

With more and more atypical femur shaft bisphosphonate fractures being reported in the literature, they should not be neglected.

Osteoporosis is an important health challenge and bisphosphonates provide most benefit with low cost. Bisphosphonates are drugs that inhibit mineralisation or resorption of the bone by blocking the action of osteoclasts. Bisphosphonates are enzyme-resistant analogues of pyrophosphate, which normally inhibits mineralisation in the bone. Their effect is dose dependent and they reduce the turnover of bone by inhibiting recruitment and promoting apoptosis of osteoclasts.

It has been discussed in medical literature that bisphosphonates are a potential cause of atypical femur shaft fractures. Atypical fractures are described as a transverse, no comminuted fracture at the sub trochanteric or femoral shaft region with a medial cortical spike at the fracture area. Other features include prodromal pain and generalised thickening of the femoral cortices on radiographs.1,2 In this case most of the above mentioned features are observed.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old woman presented to hospital with low energy trauma resulting in non-weight bearing and pain in her right thigh. She had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus type 2, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and osteoporosis. She had a right neck of femur intertrochanteric fracture in 2010 for which she had a two-hole dynamic hip screw (DHS) plate.

She was started on alendronate therapy in 2011 for osteoporosis. She had left distal radius fracture in 2013 for which she had manipulation under anaesthesia and k-wiring. She had a low energy trauma in January 2015 and was brought in with right thigh pain and non-weight bearing.

She had an x-ray right femur and pelvis showing an atypical right femur sub-trochanteric fracture. She was taken to the theatre the next day and her two-hole plate was removed without taking the lag screw and was replaced with an eight-hole DHS plate. She was started on physiotherapy and within a few weeks she was walking with a walking frame. She was followed up with regular x-ray. Her alendronate was stopped and she started on teriparatide injections. Teriparatide is a man-made form of the hormone parathyroid which exists naturally in the body.

She was undergoing this treatment when in April 2015 she again had a low energy fall and was brought to hospital with pain right thigh and non-weight bearing. On x-ray she had DHS implant failure. She had the non-union of the original sub trochanteric fracture.

She was taken to theatre again and the DHS implant was removed. A long cephalomedullary nail was inserted. After that she was again started on physiotherapy.

The patient is being followed up in outpatients on a regular basis with check x-rays. She is now walking with a walking frame and is also on teriparatide injections.

Discussion

Bisphosphonates are primary agents in the current pharmacological arsenal against osteoclast-mediated bone loss due to osteoporosis, Paget’s disease of bone, malignancies metastatic to bone, multiple myeloma, and hypocalcaemia of malignancy. In addition to currently approved uses, bisphosphonates are commonly prescribed for prevention and treatment of a variety of other skeletal conditions, such as low bone density and osteogenesis imperfecta.3

Alendronate is a commonly used bisphosphonate. It acts as a strong inhibitor of bone resorption by suppressing the activity of osteoclasts and, although this improves osteoporotic conditions, it also reduces the overall bone turnover.5

It is reported that the bisphosphonate-induced prolonged impairment of bone remodelling leads to the accumulation of micro fractures and weakening of bone.6,7,8,9

Since their introduction to clinical practice, bisphosphonates have transformed the clinical care of an array of skeletal disorders characterised by excessive osteoclast mediated bone resorption.

The risk of atypical femoral fracture has previously been thought to be associated with the use of glucocorticoids and proton-pump inhibitors.10 There is a time dependency in atypical fractures and duration of bisphosphonates. Continued use of bisphosphonate therapy beyond a treatment period of three to five years should be re-evaluated annually based on pertinent medical history and medication regimen, starting and ending with bone density and fracture history. Consideration should be given to stopping (at least temporarily) bisphosphonate therapy in those patients who are reassessed to be at low or low to moderate risk (no incident fractures, T-score > -2.0, and no other major risk factors) after a three to five year therapeutic period.11

Bisphosphonates are effective in the primary prevention of symptomatic fragility fractures during the first few years of use in female patients with osteoporosis.9

Conclusion

Prolongation of bisphosphonate treatment, however, does not appear to improve the initial benefit any further, but the risk of atypical femoral fracture increases with every year of use.

Bisphosphonate treatment should therefore be limited, regarding both treatment duration and indication for treatment.9

Figure 1. DHS two-hold plate for neck of femur fracture(click to enlarge)

Figure 1. DHS two-hold plate for neck of femur fracture(click to enlarge)

Sub-trochanteric femur shaft fracture(click to enlarge)

Sub-trochanteric femur shaft fracture(click to enlarge)

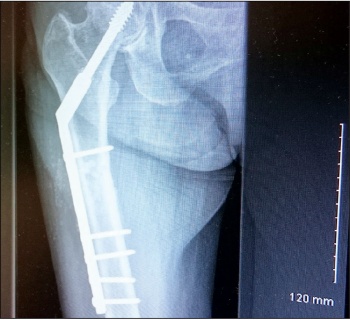

Figure 3. Conversion to eight-hole long DHS plate(click to enlarge)

Figure 3. Conversion to eight-hole long DHS plate(click to enlarge)

Figure 4. Peri-prosthetic fracture(click to enlarge)

Figure 4. Peri-prosthetic fracture(click to enlarge)

Figure 5. Lateral view of peri-prosthetic fracture(click to enlarge)

Figure 5. Lateral view of peri-prosthetic fracture(click to enlarge)

Figure 6. Cephalomedullary nailing(click to enlarge)

Figure 6. Cephalomedullary nailing(click to enlarge)