Advances in prostate cancer screening and diagnostics

When used in an organised screening-based approach, biomarkers such as PSA can impact on prostate cancer mortality

Mr David Galvin, Consultant Urologist, St Vincent’s and the Mater Hospitals, Dublin

December 17, 2015

- Article

- Similar articles

-

The rationale for the early detection of prostate cancer is simple; prostate cancer that spreads beyond the prostate is currently incurable and detecting it while still localised to the prostate maximises the chance of cure.

In 1967, pathologist Donald Gleason, described his pathological scoring system which has yet to be bettered. High-grade prostate cancer (Gleason score of 8, 9 and 10) are lethal tumours that are fatal in any group. Their detection at an early stage and appropriate treatment in a urological cancer centre will maximise the chances for cure while minimising the morbidity to the patient.

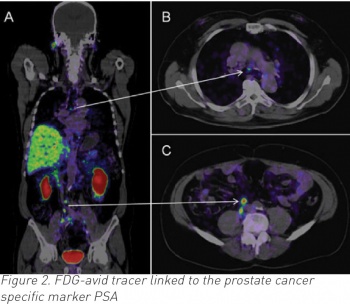

Waiting for symptoms to develop is too late. Any high-grade tumour that gives rise to symptoms is invariably at an incurable stage. The use of biomarkers such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) allows the early detection of the disease, although particularly high-grade tumours may not produce PSA and digital rectal exam (DRE) is always a necessity.

It is important to keep in mind the following:

-

One in six men in Ireland will be diagnosed with prostate cancer

-

One in six men diagnosed with prostate cancer will die from the disease every year

-

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in Irish men and the third most lethal cancer

-

Ireland has the highest incidence of prostate cancer in Europe

-

The incidence of prostate cancer will double in Ireland in the next 20 years.

Although a national strategy has been developed within the public healthcare sector, Rapid Access Prostate Clinics (RAP) services remain fragmented. Geographical variations occur in access to treatments, no oversight occurs in the private healthcare sector, and both support services and follow-up services for patients are lacking.

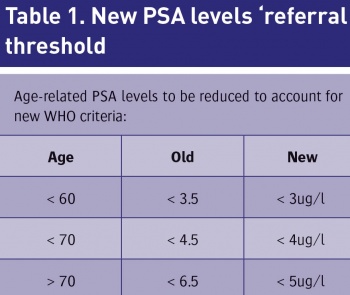

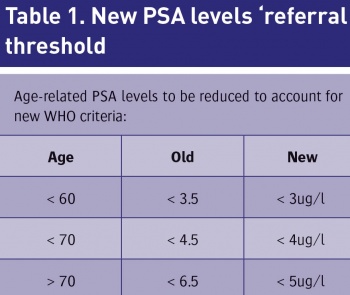

RAP clinics have for the first time allowed the prioritisation of patients at risk of cancer to access a rapid assessment service and has allowed data to be collected, analysed and the quality of the service to be monitored. The establishment of a clinical leads network supported by the National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) allows for high-level clinical communication between the HSE prostate cancer centres. This clinical leads network has recently decided to adopt new age-related PSA cut-off values that will trigger a referral (see Table 1).

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

Early prostate cancer screening studies

Prostate cancer detection has evolved a lot in the past 25 years, when many of the original screening studies commenced. Although PSA is still used, the Prostate Health Index (PHI) and 4K tests are now used in larger centres and are more accurate in selecting patients for biopsy.

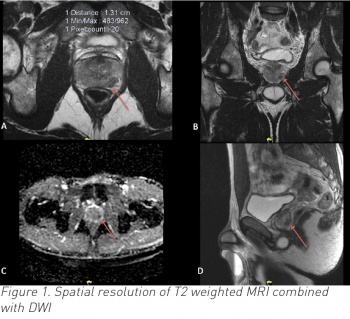

In addition, nomograms to reduce unnecessary biopsies can be applied, MRI scans of the prostate can be used to detect significant disease and targeted biopsies and transperineal biopsies are utilised to detect disease much more accurately than before. In reviewing older studies, these techniques were not available.

In the Tyrol, Austria study (1993), 65,123 men were enrolled, one-third of whom were screened using PSA at least once during the five-year study. In 2008, a 25-year analysis demonstrated a 30% reduction in prostate cancer mortality in the men of Tyrol who were screened by PSA. The authors concluded that this was due to down-staging and aggressive treatment of prostate cancer.1

A study in Quebec, Canada (1988) was heavily criticised for the methodologies used. Although 31,000 men were randomised to be screened, just 7,300 attended with only 10 patients dying of prostate cancer in the study period. Although the authors credited screening with a 62% reduction in prostate cancer mortality, an intent to treat analysis suggests no difference existed between the two groups.2

In the Swedish screening studies (1987), the first study randomly assigned every sixth man in Norrkoping to a PSA and DRE every three years. This small study was not sufficiently powered and no difference was seen in prostate cancer or overall mortality.

The second study involved just 1,782 men who underwent DRE, PSA and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) and were biopsied if the PSA was above 10ng/ml; no differences were seen between the screened and unscreened populations.3

In the US, PLCO screening study (1993), 76,693 men were randomised to either annual PSA and DRE or standard care. More than 40% of patients had already undergone prostate cancer testing, which weeded out many of the prostate cancers before the study even started. In addition, 53% of the control group had PSA testing beyond the scope of the trial so unfortunately the trial was insufficiently powered and fatally flawed.4

Contemporary prostate cancer screening studies

The European Randomised Study on Prostate Cancer screening ERSPC (1991) involved 162,000 men aged 50 to 69 years in seven European countries, of whom 72,693 were randomised to PSA testing every two to four years, with a PSA > 3ng/ml prompting a biopsy. At nine years of follow-up, there was a 20% reduction in prostate cancer mortality and a further analysis on metastatic disease demonstrated a 31% reduction at 12 years in the PSA screened group.

At the planned 13 year analysis, prostate cancer mortality has been reduced by 27%, with this figure expected to rise over time. In order to achieve this, 781 men needed to be called to screening and 27 men had to undergo treatment to save one life; remember, this was a time when active surveillance and brachytherapy and other less invasive treatments were not readily available for low and intermediate-grade disease.

This study concluded that well informed men should undergo testing if they wish to do so but that widespread national testing could not be recommended at that time, owing to the large number of men who would undergo radical treatment.5

The Goteborg trial (1994) is a Swedish cohort within the ERSPC who underwent PSA testing every two years. All men were randomised on the same day in Sweden and followed for 14 years. At this time, the screened arm demonstrates a 56% reduction in prostate cancer mortality. This led to an insignificant improvement in the numbers needed to screen, 293, and the numbers needed to treat, 12, in order to prevent one cancer death.6

In total, two meta-analyses (including a Cochrane systematic review) reviewed many of these trials, some with flawed methodologies, and concluded that screening was of little benefit. To include the earlier trials is of course erroneous and the well constructed and methodologically sound ERSPC and Goteborg studies need to be repeated on a European-wide basis.

PSA as a predictor of lethal prostate cancer

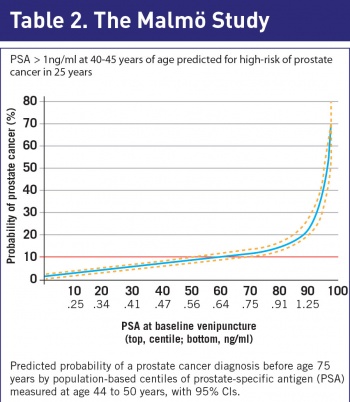

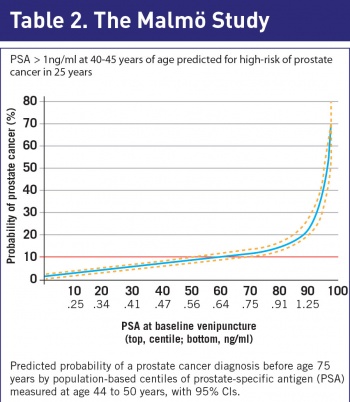

Unlike any other cancer, we now have a serum biomarker that is predictive of prostate cancer over a 25-year period. In Malmö, Sweden, investigators analysed serum samples stored in the 1960s and 1970s on men aged 35 to 50 years undergoing cardiac drug trials.7

The samples were thawed, the PSA values were calculated and using their national cancer registry, the development of prostate cancer in the intervening period was documented. Serum PSA (>1ng/ml) at the age of 45 strongly predicted for a prostate cancer over the next 25 years, defining a high-risk cohort of men (see Table 2).

Using this test, most men are at low risk and therefore can be tested infrequently, whereas the high-risk group can be screened more regularly. As a result of this trial, the European Urological Association (EAU) recommends all men to have a baseline PSA performed at the age of 45.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)