UROLOGY

Urology: Bladder problems in general practice

Commonly presenting bladder problems in general practice can have a significant economic burden on society while severely affecting patient health and quality of life

December 10, 2019

-

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a highly prevalent and complex condition with a significant economic burden to society. Overactive bladder is defined as urinary urgency, usually accompanied by increased daytime frequency and/or nocturia, with urinary incontinence (UI) (OAB-wet) or without (OAB-dry), in the absence of urinary tract infection or other detectable disease.1

OAB prevalence rates in adults are between 12-14% in those aged over 18 years and 16.6% in adults over 40. The incidence of this condition in women increases with age up to 60, levels off between 60 and 70 and then increases again thereafter.2,3 It is estimated that there are 61-71 million adults living with OAB in Europe and 11-13 million living with chronic OAB with incontinence.

OAB is considered to be a hidden condition. Many patients find it difficult or embarrassing to talk about their condition with others. They often feel that it is normal in older women and don’t wish to bother their GP about it. It is under-reported for this reason. They are also unaware that there is treatment available for this condition.

OAB has a significant economic burden associated with it. From a personal and societal perspective, the costs are significant. These include direct costs such as diagnosis, treatment and continence containment, such as incontinence pads. There are also indirect costs such as lost wages by patients and caregivers and lost work productivity due to absenteeism. This does not include the cost of pain, suffering and decreased health-related quality of life.

The estimated total national cost of OAB with urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) in the US in 2007 was $65.9 billion with a projected cost of $82.6 billion in 2020.4 The cost of medication is considerable with an estimated €16.5 million spent in 2013. On average, 31,400 prescriptions are filled on the GMS scheme every month, with a further 4,200 filled on the Drugs Payments Scheme.5

When looking at quality of life in patients suffering from OAB, most studies found that there are significant effects on daily activities, mental health and sexual function, with 65% reporting that OAB adversely affected their quality of life.3

While isolated symptoms are rare, most studies report that the greater the number of symptoms, the greater the degree of bother from OAB. Generally, urgency alone doesn’t appear to cause as much distress as it does when accompanied by two or more symptoms.

The effect of nocturia is significant, with patients reporting even one episode of nocturia as bothersome. While it is generally felt that one episode of nocturia falls within the normal clinical spectrum, there is evidence that even any episode of nocturia can have a negative effect on quality of life, sleep, work performance and general wellbeing.3

The anatomy and physiology of the bladder are complex. Reduced activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) results in relaxation of the detrusor muscle, closure of the sphincter, and bladder filling. When the volume of urine in the bladder reaches 200-400ml, the sensation of urge to void is relayed via the spinal cord to the brain centres. Voluntary voiding involves the parasympathetic nervous system and the voluntary somatic nervous system. Influences from these systems cause contractions of the detrusor muscle and corresponding somatic nervous activity, leading to sphincter relaxation and voiding. Interruption of these pathways leads to symptoms.

Aetiology and risk factors

There is a multiplicity of factors that contribute to the development of OAB symptoms. There are known age-related changes that occur in the bladder, affecting bladder contractility as well as increasing detrusor overactivity and decreasing urethral closure pressure. The genitourinary syndrome of menopause with resulting atrophy of urethral areas may contribute to symptoms of dryness, burning, itching, dyspareunia and infection as well as frequency and urgency. Other risk factors include difficult vaginal deliveries, high infant birth weight, previous hysterectomy and other pelvic surgery or radiotherapy. Smoking, high body mass index and constipation are all associated with increased risk of UI.6

Pathophysiological causes of urinary incontinence include lesions in higher micturition centres and may be associated with Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and obstructive sleep apnoea. In addition, issues with mobility and dexterity as well as reaction time can contribute to urinary incontinence.

Diagnosis and evaluation

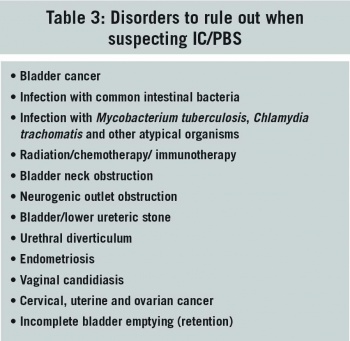

Common reversible causes of urinary incontinence include urinary tract infection, constipation and medications. Patients with symptoms should undergo a complete medical evaluation to rule out reversible causes in the first instance. As a minimum, abdominal palpation to rule out gross abdominal or pelvic mass and inspection of external genitalia should be carried out.7

Women presenting for the first time should have a urine dipstick checked for blood, protein, glucose, leucocytes and nitrates and if positive a mid-stream sample should be sent to check for culture and analysis of antibiotic sensitivities.

If there are symptoms of voiding dysfunction or recurrent infections, an assessment of post-void residual should be made by bladder scan or catheterisation. Patients should be asked to complete a three-day bladder diary and given information on lifestyle changes they can make. The diary needs to record times and amounts of urine passed as well as leakage episodes, pads usage, fluid intake, degree of incontinence and urgency. It should cover both working and leisure days.

Women should be asked to reduce their caffeine intake. Bladder training should be offered for a minimum of six weeks. This can have better results if supervised by specialised physiotherapists or nurse continence advisors.8 If bladder training is not effective, then OAB medication may be offered.

Medications for OAB

There are several medications licensed for the treatment of OAB in Ireland. They include anticholinergics and antimuscarinics, which act by competitive antagonism of acetylcholine at postganglionic muscarinic receptors, causing relaxing of bladder smooth muscle. This in turn results in an increased bladder capacity and decreases urgency and frequency. Mirabegron is a beta3-agonist which activates beta adrenoceptors in the detrusor muscle and trigone area of the bladder, allowing urine storage by detrusor relaxation.

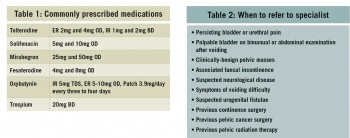

In general, there is no recommended first-line medication. The HSE Medicines Management Programme has tolterodine ER as first-line choice for treatment of OAB.5 However, the evidence for treatment for one medication over another has only shown modest differences.7,9 International guidelines do not identify one preferred medication.8 If the first medicine for OAB or mixed UI is not effective or well-tolerated, an alternative medication should be offered.

Transdermal OAB treatment can be useful in women unable to tolerate oral medications. Intravaginal oestrogen can be used to treat postmenopausal women with vaginal atrophy. Medication should be reviewed at four weeks to assess efficacy,4 although in clinical practice reviewing after 12 weeks of use is in keeping with clinical studies unless intolerable side-effects occur.

Typical antimuscarinic side-effects include dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision and drowsiness. Prolongation of the QT interval has occurred with tolterodine and caution should be used. Antimuscarinic drugs are contraindicated in myasthenia gravis, significant bladder outflow obstruction, severe ulcerative colitis, toxic megacolon and in gastrointestinal obstruction or atony. Mirabegron has reportedly less antimuscarinic side-effects but has reported tachycardia as a side-effect. See Table 1 for commonly prescribed medications. Flavoxate, propantheline and imipramine are rarely used.

Anticholinergic use in the elderly

The extent to which anticholinergics impair CNS function is proportional to their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. It is of concern that up to 32% of the elderly use two or more drugs with anticholinergic effects.10

Oxybutynin, which is a lipophilic molecule with neutral polarity, is the one most likely to cross the blood-brain barrier. Despite this, it is still widely used to treat OAB in older patients because of the low cost. Tolterodine has low lipophilicity and is thought to be more suitable for older patients. Tolterodine IR and oxybutynin IR have a similar efficacy, but the former has fewer adverse effects in patients over 50 years of age. Trospium is the least likely to impair CNS function based on neuropsychological and co-ordination tests. Fesoterodine is also well tolerated in the elderly.11

Combination therapy

Combination therapy may be considered in patients who fail single medication use. Anti-muscarinic and beta3-adrenoceptor agonist medication may be used in combination if monotherapy with either alone fails.8

When to refer to a specialist

Patients who do not respond to conservative treatment, lifestyle changes and medication or if they meet the criteria in Table 2 should be referred for specialist review.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)