CHILD HEALTH

A stepwise approach to nocturnal enuresis

Enuresis is an area with huge potential for management in the community

September 1, 2013

-

Enuresis is the involuntary discharge of urine at night, in a child aged five years or older, in the absence of congenital or acquired defects of the central nervous system or urinary tract. Enuresis is more common in boys and up to 75% of patients have a family history of bedwetting.1

Why is this relevant to GPs?

Enuresis is an extremely common problem. It affects about 15% of five year olds.1,2 The incidence gradually decreases over childhood, with 5% of 10 year olds affected and <1% of adults affected.1,2 Spontaneous cure rate is about 14% a year.1 Enuresis is an area with huge potential for management in the community setting.

Primary enuresis is where the child has never been dry for a period of three to six months. Secondary enuresis is recurrence of bedwetting after a period of dryness for at least three to six months.

Monosymptomatic children have night-time wetting only, with no daytime symptoms and no lower urinary tract symptoms. Non-monosymptomatic children can have daytime wetting or dampness, or lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as frequency or dysuria.

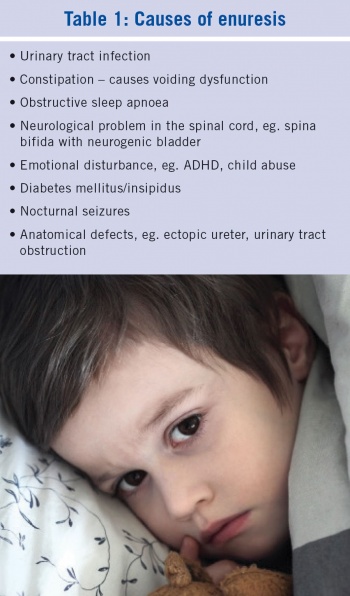

These mono and non-monosymptomatic definitions are important as they have different prognostic and management significance. Monosymptomatic children can be managed by their GP and are unlikely to need any complicated investigation. Non-monosymptomatic children have a poorer prognosis and frequently can have an underlying cause (see Table 1).

Enuresis is a source of embarrassment and low self-esteem in children and has been reported to be a trigger for abuse in certain circumstances. It can place a psychological stigma on the child and stress on the family. There is considerable emotional morbidity attached to the whole family when dealing with enuresis.

Diagnostic work-up

The first step is to complete a standard history to get an overview of the circumstances surrounding the wetting, to rule out constipation and to complete a fluid-voiding diary to establish if the child has monosymptomatic or non-monosymptomatic enuresis.

Included in the fluid-voiding diary should be a record of the fluid consumption to ensure the child has an adequate intake of 800-1,400ml a day, and the urinary frequency. The volume of urine passed at night can also be recorded; this can be calculated as the difference in the dry versus wet weight of a pull-up plus the volume of urine produced first thing in the morning. This nocturnal voided volume (NVV) should be less than (age in years x 30 + 30ml) x 1.3.

In this way you can accurately differentiate between mono and non-monosymptomatic enuresis. It might sound like a lot of work for parents but remember, enuresis results in poor sleep for the whole family and parents are usually desperate to find a cause and cure.

Many children with bedwetting drink little fluid at breakfast and throughout the school day. They then arrive home from school hungry and thirsty, and most of their fluid intake occurs in the latter half of the day, favouring a nocturnal polyuria pattern that will be revealed by the fluid-voiding diary and NVV.

Physical examination should include an abdominal, neurological and spine exam, and growth should be plotted on a centile chart. Large tonsils may indicate obstructive sleep apnoea. A hair tuft on the sacrum may reveal spina bifida occulta. The first investigation is a urine dipstick to outrule occult infection and proteinuria. Blood pressure should also be checked. Ultrasound of the renal tract is not recommended routinely except when a pathological cause is suspected or a voiding diary reveals voiding dysfunction.

Therapeutic approach

The therapeutic approach is defined by the age/maturity of the child. Many of these mechanisms require cooperation from the child and a heavy investment of the parent’s time. Education of the parents and child about enuresis using ‘the three systems’ approach is important.

The ‘three systems’ approach is a model used to explain visually to the parents and child about the three main causes of enuresis:

- Monosymptomatic enuresis due to arousal difficulties

- Monosymptomatic enuresis due to reflex leaking of urine (nocturnal polyuria)

- Non-monosymptomatic enuresis due to bladder or bowel dysfunction (lower urinary tract symptoms).

General advice

First try to minimise the embarrassment/anxiety of the child. Encourage parents to share their enuresis experience with the child. Positivity and motivation are key. Have the child look into the mirror each morning and repeat the positive affirmation ‘I am the boss of my bladder’. The child needs to feel empowered and not helpless or punished. This is the basis of the use of star and reward charts where activity to help with continence (such as filling out the diary and changing bedclothes) and not just dry nights are rewarded. The best reward for the child is for the parent to spend dedicated time with them; for example play a football game at the weekend.

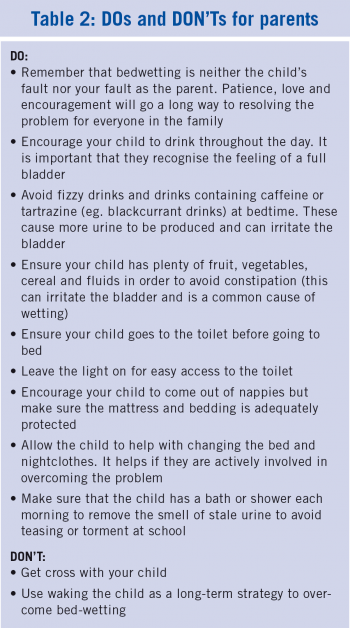

Children should be instructed to drink liberally during the day (aim for >50% of daily intake before 12pm), but not to drink excessively with the evening meal and in the evening. The child should be toileted every night before bed. Commonsense modifications may be needed for children who participate in sports in the evening times. No child should go to bed thirsty and fluid restriction or lifting during the night is not a useful strategy to achieve long-term dryness. (See Table 2 for a list of Dos and Don’ts for parents). The parent can find general advice on the website www.bedwetting.ie

Under sevens

Children under the age of seven can be reassured that this is a very common problem and most can expect to be dry by seven years of age. Spontaneous cure rates are 14% a year. Star and reward charts may be helpful in this age group. The parents need particular support and advice as this can be a frustrating time for them, with significant sleep disturbance and expense.

Over sevens

Once aged seven, monosymptomatic children who remain problematic can be referred for a trial of an enuresis alarm system. This is a simple mechanism that causes an alarm to sound when the child wets. The aim is to gradually train the child to wake up when the bladder is full or to hold on through the night. Alarms are normally available through local community services/enuresis clinics, which may be run by a public health nurse in conjunction with a paediatrician.

Desmopressin is an antidiuretic hormone analogue and is commonly prescribed for enuresis. It reduces wetness in 70% of children (40% totally dry, 30% drier than before) and is convenient and easy to use. It is costly however, and usually results in relapse when discontinued. It can be helpful to reduce wetting in the short term or for ‘emergency’ situations such as a family holiday or sleepovers. The usual dose of desmopressin is 120 micrograms sublingually at bedtime. There is a risk of hyponatraemia with this medication.

Oxybutynin can be useful if the patient has symptoms of bladder instability. Tricyclic antidepressants are not indicated.

Useful websites

www.nice.org.uk - see guideline on nocturnal enuresis.

www.eric.org.uk - a UK based childhood continence charity, lots of downloadable information and resources including the charts, appropriate for children, parents and professionals.

www.bedwetting.ie - useful for parents.

References

- Cendron M. Am Fam Physician 1999 Mar 1; 59(5):1205-1214.

- Butler R, Heron J. The prevalence of infrequent bedwetting and nocturnal enuresis in childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology 2007; 42 (3); 257-264

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)