RESPIRATORY

Allergy immunotherapy

The management of allergic diseases, in particular asthma and rhinitis, has been moving beyond the symptomatic with new developments in the field over the past five years

May 1, 2013

-

Allergy as a specialty does not exist in Ireland to a level that an effective service is provided to patients in a consistent and equitable fashion. The main reasons for this are historical fears about the safety of subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy (SCIT) (or ‘allergy shots’), coupled with the efficacy of short-term ‘symptomatic’ treatments. The practice of SCIT in primary care ended in 1986 in the UK and Ireland as a result of a report of the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) published in the BMJ in 1986.

Prior to this, SCIT was one of the commonest modalities used in the management of allergic rhinitis (AR) (both seasonal and perennial) and in allergic asthma (AA). Therapy was usually initiated in hospital and thereafter administered by GPs. The CSM advice was effectively that GPs should no longer give allergen injections, that patients with asthma should not be treated by SCIT, and that there should be adequate monitoring and post-injection observation (initially for two hours). This effectively ended SCIT as a primary care-delivered treatment in the UK and Ireland.

There were also serious accompanying effects for service development for the existing, but less well known, allergic diseases. These include allergies to bee and wasp venom, drugs, peanut and other food allergy in children in particular, and the new issue of health care-related latex allergy. These now represent a huge unmet need with few, if any, centres in Ireland offering structured services for adults and children. This is in sharp contrast to other jurisdictions, such as the US and mainland Europe, where allergy is a major medical specialty (eg. 100 paediatric allergists in Finland, population 5.2 million) and where SCIT has continued to be widely practised for the past 100 years.

Associated with this is the fact that symptomatic therapies for AA and AR, such as corticosteroids, anti-leukotrienes and anti-histamines, are remarkably effective for symptom control and are relatively free from serious side effects. These treatments by definition improve symptom control but unfortunately do not affect the natural history of these diseases, with the disease recurring soon after treatment is stopped. In Ireland and the UK, this has been the predominant therapeutic approach to the management of asthma and rhinitis in the latter part of the 20th century and up to recently. The obvious short term efficacy of these therapies has resulted in there being less focus on their allergic mechanisms and so less focus on therapies directed at the cause of these diseases, rather than symptom control. The evidence, however, is now available and provides a compelling argument that treatment of the underlying allergic diathesis with allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) in AR, not only improves symptoms during and for at least three years post-treatment, but may prevent the development of de novo asthma in these patients. Now, a century after SCIT was first administered to patients with grass pollen hay fever in the UK, the landscape is changing internationally in the management of allergy and its related diseases which is having immediate implications for such management in Ireland. This has resulted for two reasons:

- The efficacy of the monoclonal antibody anti-IgE in asthma

- The recent commercial availability of safe oral sublingual allergy vaccines – sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT).

History of allergy, IgE and its role in asthma

The history of allergy is informative to this debate. In the 19th and early 20th century it was noticed that certain individuals developed hypersensitivity after administration of foreign proteins then used in contemporary treatments (eg. antisera) or to innocuous substances such as grass pollen. The more immediate of these manifestations, eg. asthma, rhinitis and anaphylaxis, became known as the allergic diseases which, in the 1920s, were found to be associated with a transmissible agent.

For example, a previously asymptomatic individual developed transient asthma to horse hair a few days after receiving a blood transfusion from a patient who had horse asthma. In addition, when serum from donor allergic individuals was injected into the skin of non-allergic recipients, it was possible to elicit a transient positive skin reaction at this recipient dermal site to injected allergen in the non-allergic individual. This became known as the eponymous Prausnitz-Kustner reaction (the P-K reaction) which was soon replaced by the more convenient (and safer!) skin prick test. This transmissible agent was known as ‘reagin’ and was subsequently identified in 1966 as being the antibody, IgE.

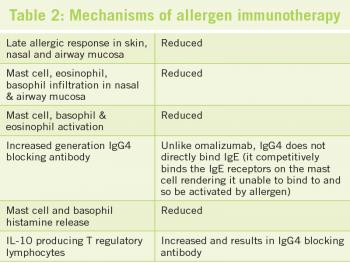

We now know that allergic individuals produce allergen-specific IgE in response to such innocuous allergens as pollen, mould, animal dander and dust mites. The IgE thus produced can bind to circulating basophils; however, in the main, they dock on to the surface of the abundant tissue mast cells found in the submucosa and dermis. On subsequent exposure to allergen by either the inhaled, oral, subcutaneous or IV routes, the allergen binds to its specific binding site on the ‘docked’ IgE, so leading to mast cell (basophils in the case of in vitro exposure) activation and release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as histamine and leukotrienes.

Long considered a marker of allergy, IgE is now regarded as pathogenic. Indeed, this has now been established beyond all doubt since 2003 when the monoclonal IgG1 anti-IgE molecule, omalizumab became available for clinical use. Omalizumab binds to free serum IgE with which it forms complexes that cannot subsequently bind to its IgE receptors on mast cells, so preventing their activation. This leads to marked down regulation of these now redundant receptors within a few weeks. Therefore, omalizumab neutralises IgE-mediated effects. This treatment is currently indicated for selected patients with severe allergic asthma (GINA 5) and can be extraordinarily effective in such patients.

Our own experience of 34 such patients has shown reductions of 73% in exacerbation frequency, 75% in use of rescue medication and 91% reduction in hospitalisations, after only four months of therapy. In addition, there is evidence that this improved asthma control persists up to three years post treatment cessation, ie. omalizumab may have a disease modifying effect. In terms of duration of therapy, and in the absence of evidence to the contrary, our practice is to treat for a three year period and to thereafter wean treatment for an additional year, ie. a total of four years therapy. Therefore, there is now irrefutable proof of concept that allergic mechanisms, and its central molecule IgE, underpin the pathogenesis of diseases such as asthma and rhinitis.

The annualised costs of omalizumab therapy, however, can be as high as €30,000 per patient depending on IgE levels and BMI and, therefore, at present it is only indicated in those patients with the severest allergic asthma, estimated at about 350-400 patients nationally. The most recent information from the National Asthma Programme (NAP) suggests that c.460,000 patients actually have some degree of asthma in the country, ie. 21% of children and 8% of adults, of which at least 80% will have an underlying allergic mechanism. Thus, because of the high costs associated with omalizumab, and the lack of alternatives, < 0.001% of allergic asthmatics currently receive a potential disease-modifying agent.

The treatment of asthma as currently practised in Ireland is as a result, largely symptomatic and based on international GINA guidelines and includes glucocorticoids, beta-2 agonists, anti-leukotrienes and theophyllines, administered in a step-up/step-down fashion, depending on disease severity. Other than some evidence for early and aggressive management of asthma in the paediatric population, there is little evidence that any of these symptomatic treatments can alter the natural history of the condition.

Allergic rhinitis and allergen-specific immunotherapy

In the UK, the current indications for AIT are:

- IgE-mediated seasonal pollen-induced rhinitis from the age of five. Asthma, if present, must be stable with FEV1 > 80% predicted (thus asthma is not a contraindication but it must be recognised and stable)

- Selected patients with AR secondary to animal dander or house dust mite allergy from the age of five

- Systemic reactions to bee and wasp venom (which is not the subject of this review).

AR, both seasonal and perennial, affects at least 25% of the adult population, is a major cause of morbidity and is a precursor for asthma development, particularly in children. Indeed, AR often constitutes an early stage in the natural history of asthma, with up to 40% of AR patients developing asthma in later life. The evidence is now compelling that the inclusion of AIT in the management of AR can improve asthma control and may even decrease the ‘allergic march’ along its journey from eczema, AR to asthma if treated early enough in children.

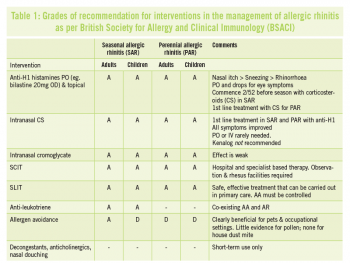

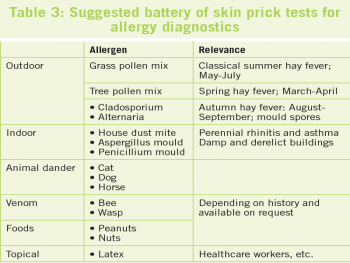

In Ireland, the most common causes of seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR) are grass and tree pollens, whereas the most common cause of perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR) is house dust mite. These patients are looked after by their GPs, paediatricians, ENT surgeons, clinical immunologists and some respiratory physicians, often without recourse to a full allergy assessment, and so treatment is largely symptomatic including H1 antihistamines, glucocorticoids, decongestants, anticholinergics and antileukotrienes. Table 1 summarises and grades the interventions available for AR. Treatment with triamcilonone (Kenalog) and other depot steroid preparations is not recommended by any international guideline. In addition, only 0.014% of the paediatric population with AR is receiving allergen immunotherapy even though there is compelling evidence that it may prevent these children from subsequently developing asthma. There is no doubt in my view that the management of AR in Ireland, particularly with the low uptake of immunotherapy, lags far behind that of the UK, which in turn lags far behind that of mainland Europe, the US and Australia. This has major implications, not just in terms of symptom control, but also potentially in terms of missing an opportunity to prevent the development of subsequent asthma.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)