CANCER

HPV and the diagnosis and treatment of head and neck cancer

An Irish perspective

April 27, 2017

-

Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been accepted as a causative agent in a subgroup of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) in the oropharynx. The incidence of these HPV-related tumours is increasing in many developed countries, but national data was lacking until a recent publication of a cohort of 226 patients found that HPV-related tumours represent approximately 31% of oropharyngeal tumours in Ireland, consistent with other European figures.1

A larger study of the burden of HPV in head and neck cancer in Ireland has begun; the epidemiology of HPV in oral cancer (ECHO) study.

Incidence and prevalence

Of cancers in the head and neck, SCC comprises approximately 95%. HNSCC is the sixth most common type of cancer worldwide with approximately 633,000 new cases diagnosed and 355,000 deaths annually.2 Broadly, it is subdivided into tumours of the oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx, hypopharynx and larynx. Over the past 10 to 15 years, the traditional paradigms of HNSCC have been changing significantly, with the decline in smoking trends and the rise of HPV-related cases.

Based on the cancer atlas, HNSCC is the ninth most common cancer in Ireland,3 accounting for 1.7% of all malignant neoplasms in women and 3.9% in men. The average number of new cases diagnosed each year, from the latest data between 2010 and 2012, is approximately 161 in women and 413 in men. In males, the incidence of new cases decreased by 1.5% per annum between 1994 and 2000 before increasing by 1.1% per annum between 2001 and 2013, while females showed an overall increasing incidence of 1.4% per annum between 1994 and 2013.4

There is significant worldwide geographical variation in the incidence of head and neck cancer with incidence rates usually following trends in tobacco use, such as in the USA where there has been a decline in correlation with reduced smoking habits, while the age standardised incidence of HNSCC has increased in areas of Asia due to high rates of tobacco use.5 The estimated incidence in Ireland is 8.3 per 100,000 and males are significantly more affected than females.

The Irish age-standardised incidence rate for cancer of the tonsil increased by 4.9% (95% CI: 0.8-8.9%) annually for women and 4.3% annually for men between the periods 1994-1998 and 2004-2008. Meanwhile the population-level incidence of HPV-positive oropharyngeal SCC in the United States increased by 225% between 1988 and 2004, with a concomitant decline by 50% for HPV-negative oropharyngeal SCC.6

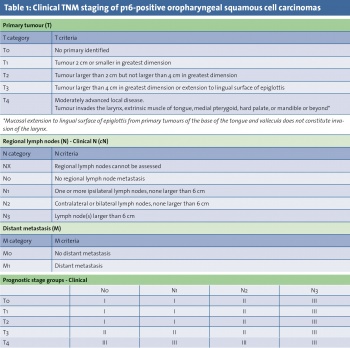

Oropharyngeal cases account for approximately 10% of HNSCC.7 Worldwide, there were an estimated 85,000 new cases of oropharyngeal SCC in 2008. Within the oropharynx, 88-98% of cases arise from the tonsils or base of tongue.8,9 However, determining the exact site of origin, particularly in larger tumours, can be challenging and lead to misclassification. The recent 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging manual has recognised the shift in head and neck cancer trends by acknowledging the emerging role of HPV; the new clinical staging system for oropharyngeal SCC is shown in Tables 1 and 2, with a separate staging system for p16-positive cases.

HPV has been linked to the pathogenesis of SCC since the 1970s10 and, in 1995, it was recognised by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) that high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 were carcinogenic in humans.11 The role of HPV in cervical cancer is well described with nearly all cervical cancer cases being caused by HPV.12

Over 200 different genotypes of papillomaviruses have been identified, but only some are associated with oncogenic potential (eg. HPV 16, 18, 31, 33), while others are associated with benign lesions such as genital warts and recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (eg. HPV 6, 11).

Risk Factors and symptoms

There are a large number of potential risk factors associated with HNSCC, but the predominant risk is with a long history of heavy smoking and alcohol consumption. Other risk factors include poor oral hygiene, a diet low in fruit and vegetable consumption, chronic inflammatory disease in the oral cavity, immunodeficiency or HIV infection, previous radiation exposure, betel nut chewing, occupational exposures such as leather dust or asbestos and underlying genetic factors such as Fanconi anaemia.13

HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC has been described as an epidemic.14-18 Current data from studies that use HPV E6/E7 mRNA in situ hybridisation suggest that HPV-related HNSCC is rare in non-oropharyngeal HNSCC sites,19 however the role of HPV in non-oropharyngeal sites remains unclear20 and a causative relationship at these sites has not been established.21

HPV-related oropharyngeal cases are generally identified in younger patients than other SCCs, in a higher socio-economic group and in a higher proportion of males than females. They are also more common in cases of immunodeficiency. In cases of unknown primary carcinoma, particularly an adult presenting with a cystic neck node, HPV-related disease is a high likelihood.

Symptoms or findings can include, but are not limited to, sore throat, odynophagia, dysphagia, referred otalgia, trismus, neck mass or distant metastatic disease. Radiologic imaging with computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is performed to stage tumours, with increasing use of positron emission tomography. Biopsies are performed with evaluation under general anaesthetic to assess tumour extent and for other synchronous disease.

These SCCs can be found in patients with no history of heavy smoking or drinking, but there is often also a history of these risk factors in HPV-related cases. It is therefore important to establish which oropharyngeal cases are linked to HPV, as this may affect treatment decision making. All cases should be discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting in a head and neck cancer centre. A surrogate marker for HPV infection, p16, is now routinely examined in cases of oropharyngeal tumours. Functional inactivation of Rb by the HPV E7 oncoprotein results in overexpression of p16 tumour suppressor protein, which is a CDK4A inhibitor.13 Cases demonstrating p16 positivity (>70% staining on immunohistochemistry) have a significantly improved prognosis compared to those that are p16 negative.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)