PAIN

Interpreting recent findings on spinal pain

New research into the nature of spinal pain point to a complex bio-psycho-social relationship

April 9, 2014

-

Spinal pain is one of the most common reasons for patients to present in primary care.1 While spinal pain can be quite disabling in a small proportion of people, most people who develop it recover well and lead full, active lives.1

Despite increasing expenditure, most spinal pain has no specific diagnosis2 and many common interventions have demonstrated little effectiveness.3,4,5,6,7 Typical clinical practice in recent decades may have in fact increased the disability associated with spinal pain,8 such that spinal pain has been labelled ‘a 20th century healthcare disaster’.9

This article aims to use recent findings in spinal research to help address some key questions for primary care clinicians regarding spinal pain including:

- What are the main risk factors for spinal pain?

- How can we best identify, and assist, those patients most at risk of chronic, disabling spinal pain?

What are the main risk factors for spinal pain?

Biomechanical factors including prolonged occupational sitting,10 standing,11 lifting,12 manual handling,13 bending14 or twisting14 are no longer considered major risk factors for the development and maintenance of spinal pain. This is not to suggest such postures and activities are irrelevant in spinal pain, or that they are never associated with acute onset of spinal pain. Rather, it highlights that these postures and activities are actually performed as frequently in people without spinal pain.

Consistent with this, uni-dimensional ergonomic interventions aimed at improving the way in which such tasks are performed have minimal effectiveness.15 Similarly, many ‘pathologies’ observed on spinal imaging are equally common among people without spinal pain, and have little correlation with clinical findings.16

In contrast, several other factors have been linked to people developing disabling spinal pain. These include a widespread distribution of pain,17 poor general health,18,19 depression,20 anxiety,21 chronic stress,22 acutely stressful traumatic events,23 fear,24 poor self-efficacy or coping,25 catastrophic thoughts,26 a pessimistic outlook on prognosis,27 a perceived danger of being physically active,28 reduced spinal range of motion,23 or excessively guarded or careful movement.29,30

To summarise, the primary risk factors for chronic disabling spinal pain are not biomechanical or patho-anatomical in nature. Instead, the range of factors involved reflects the bio-psycho-social nature of spinal pain.31 It appears that the physiological effects of a range of psychosocial and cognitive factors abnormally sensitise the central nervous system, such that pain thresholds are lowered. This heightened sensitivity is compounded by unhelpful physical factors such as abnormal patterns of spinal movement.

Therefore, a mix of physical, lifestyle, psychosocial and cognitive factors interact in chronic spinal pain, and management strategies may need to address this.

Identifying, and assisting, those most at risk of chronicity

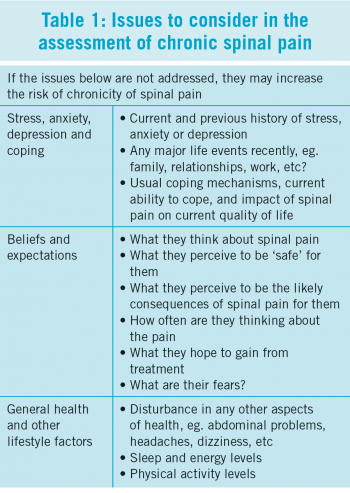

Similar to any patient presentation, screening for the presence of any ‘red flag’ pathologies which may require specialist referral is essential.32 Thereafter, a detailed subjective history is critical, and provides greater insight than the physical examination. The established relationship between the primary care clinician and patient can also provide useful insights into the patient’s life. A guide to some issues worth considering in the assessment of spinal pain is provided in Table 1. In particular, determining if changes in any of these factors coincided with the onset of (or an increase in) spinal pain is very relevant.

Relatively brief questionnaires,33,34 which cover issues such as those listed in Table 1 have been shown to be valid methods of identifying patients at risk of developing chronic, disabling spinal pain.

This risk profiling approach can then be used to prioritise management strategies:

- Low-risk patients report relatively localised pain, with low levels of distress, and little or no psychosocial factors. This group should be educated on the likely, positive prognosis for their spinal pain. They should be offered simple pain medications, and encouraged to return to their usual levels of physical activity

- Moderate-risk patients report greater pain and distress, and some psychosocial risk factors are present. This group should receive the aforementioned education and advice, as well as conservative rehabilitation such as physiotherapy

- High-risk patients report high levels of pain and distress, and several psychosocial risk factors are present. This group should receive the aforementioned education and advice, as well as conservative rehabilitation with a greater emphasis on addressing psychosocial obstacles to recovery.

Primary care professionals can thus help prioritise the minority most at risk, while providing less costly, yet speedy and effective treatment for other patients. Some specific approaches which have been demonstrated to improve outcomes, and which are reflected in several clinical practice guidelines35,36 include:

- Encourage patients to avoid bed rest, and to return to their usual levels of physical activity by reducing fears about the perceived safety of physical activity28,37

- Provide simple analgesics to reduce pain in the short-term

- Avoiding referral for spinal imaging unless considered medically required due to the presence of red flags, or at least delaying referral to allow time for natural recovery has been linked to reduced rates of surgery and disability16,38

- If imaging is undertaken, assist patients to interpret the findings appropriately. Reassure patients that disc degeneration and other signs previously considered as ‘wear and tear’ are common among people without spinal pain, and have very little relationship to pain and disability. Avoid using technical language which implies significant pathology and spinal vulnerability as this increases patient fears39

- In a minority of cases where a close correlation exists between the clinical presentation and specific pathology on spinal imaging, referral for surgical opinion may be worthwhile if conservative rehabilitation has been unsuccessful

- In addition, some simple physical examination procedures can help identify which specific spinal tissues, if any, are most closely related to the pain.40-43 However, in people with chronic spinal pain, such procedures are complicated by heightened tissue sensitivity, meaning they should only be considered in conjunction with the patient history

- Avoid, and challenge, the perception that spinal pain usually reflects significant spinal damage. Reinforce the concept that spinal pain does not automatically suggest significant spinal damage, and instead reflects the sensitivity of the nervous system44

- Similarly, reassure patients that perceptions of spinal subluxation,45 pelvic asymmetry,46 and other feared malalignments rarely, if ever, exist and are not linked to spinal pain

- Reduce catastrophic thinking, and set specific, realistic rehabilitation goals26

- Improve patient perceptions about the consequences of spinal pain, such that long-term disability is not seen as inevitable27

- Empower patients to self-manage by improving their perception of their own ability to cope with pain, and their ability to participate in rehabilitation25

- Encourage patients to restore normal range of movement, and normal patterns of movement in everyday tasks. This may involve referral for a specific exercise programme, or participation in a more comprehensive programme encompassing physical, psychosocial and cognitive contributors to their spinal pain.47

Conclusion

Spinal research challenges previously held beliefs about the close relationship between patho-anatomical changes and pain. Instead, psychosocial and cognitive factors, along with some physical factors such as guarded movement patterns, are more relevant predictors of chronicity.

Acute spinal pain usually resolves quickly, with early pain relief and restoration of physical activity linked to recovery and less recurrence.

Patients with chronic spinal pain may present with a mix of physical, psychosocial and cognitive issues which contribute to their pain.

The role of the primary care professional is to help patients return to full health by addressing whatever issues are relevant to their pain. This may include provision of pain relief, or addressing physical impairments such as changes in range of motion or muscle tone. It should, however also consider the role of psychosocial and cognitive factors in the patient’s pain.

This article outlines how using a simple risk stratification approach can help identify the mix of factors associated with an individual patient’s spinal pain. This reduces the likelihood of unnecessary, expensive and often unhelpful tests being performed. Such an approach not only reduces disability, but has also been shown to improve cost-effectiveness.38,48

Through using such an approach in primary care, those most at risk of chronicity may be identified at an early stage, and suitable strategies implemented. This should lead to more positive outcomes for spinal pain than in recent decades.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)