CHILD HEALTH

Management of dangerous vs self-limiting fever in young children

Most cases of pyrexia are viral and self-limiting, but it is important to recognise the exceptions

November 1, 2012

-

The febrile child is a common paediatric presentation in both primary care and the emergency department. Studies from the UK show that over one-third of contacts with out-of-hours services are about children under five years of age, and 52% of these calls are due to a febrile child.1

Despite being so common, the febrile child still remains diagnostically challenging as distinguishing a routine, self-limiting viral illness from a serious bacterial infection is not always straightforward.

Fever has a reputation of being a sign that needs urgent medical attention, whereas in reality, the vast majority of children will have a mild, self-limiting illness and close observation for specific signs of serious infection is all that is required. The notable exception to this is infants under three months of age, whose risk of having a serious bacterial infection if presenting with a fever is significantly higher than in older children.

Diagnosis of fever

The diagnosis of fever often begins with the parent’s perception that the child feels warm or hot. Subjective detection of fever by parents and carers has been relatively well studied and the sensitivity of palpation for the detection of fever ranges from 74% to 97%.2-5 Hence, parental perception of fever should be taken seriously.

Mercury thermometers are no longer recommended for use in children, and for children under five years of age, oral and rectal thermometers are also not advised. The accuracy of forehead strips is questionable. Three methods for taking temperatures in this age group are currently recommended:

- Infrared tympanic thermometer

- Electronic thermometer in the axilla

- Chemical dot thermometer in the axilla.

Once fever is established, the vast majority of parents will make contact with the health service. One study showed that 85% of parents made contact with a healthcare professional within 24 hours of their child having a temperature. Once this contact is made, the child will undergo a clinical assessment.

For the vast majority of these children, a condition that can be diagnosed, assessed and treated appropriately there and then or with simple follow-up arrangements will be found. However, many will have fever where no source can be identified. Assessing these children’s needs can be more difficult.

Healthcare professionals need to be fully conversant with the norm or near norm to recognise the ill child with a possible serious bacterial illness.

Examination

In infants over three months of age, a careful history, observation of the child and a complete physical examination should be able to identify those needing further evaluation or referral to hospital. One should have a low threshold for obtaining a urine sample for urinalysis and if the urinalysis is abnormal, a urine culture should be sent and empirical antibiotics commenced.

Examination for rashes is important if one wishes to pick up early invasive meningococcal disease (IMD). Up to 20% of meningococcal disease cases do not have a rash and in some patients the rash may be macular and later evolve into a non-blanching or petechial rash.

Look in the nappy area and the feet, as a petechial rash may only be present at these sites. In general terms, a rash which is present only in the distribution of the superior vena cava (head, neck and thorax) is most unlikely to be due to IMD.

‘Eyeballing’ the child is not enough and the child should be stripped down for a complete examination. Early meningococcal disease or other serious bacterial infection may be quite indistinguishable from a viral illness.

Key clinical questions

The clinical questions one should ask to help identify the serious ill child are as follows:

- What is the infant’s cry like? Is it strong or weak, is it a high-pitched cry or a moan?

- How does the infant react to his/her parents? Enquire also if the infant perks up once the fever settles

- Ask about the state of arousal of the infant and whether he/she awakens quickly

- Assess the infant’s colour looking for signs of pallor, cyanosis or mottling

- Assess the hydration status of the child

- Assess the social responses of the infant. Does he/she smile?

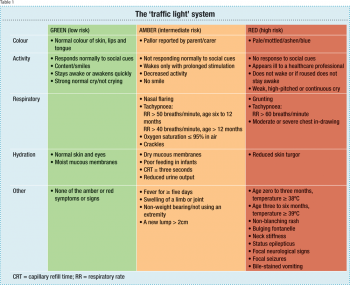

Serious bacterial illness is most unlikely in a smiling infant. The NICE guidelines on the febrile child established the ‘traffic light’ system for risk stratifying children.7 They divide them into high, intermediate or low risk of having a serious bacterial infection and suggest recommendations on appropriate management of children in each category. Table 1 lists the signs and symptoms to look out for.

(click to enlarge)

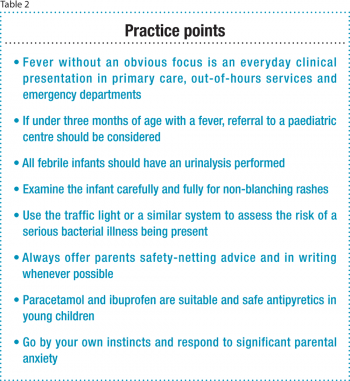

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)