HEALTH SERVICES

REHABILITATION

What happens at the physiotherapy clinic?

What exactly physiotherapists do and which patients benefit most from being referred by their GP?

December 7, 2012

-

Have you ever wondered what goes on when your patient attends a physiotherapist for treatment? By the end of this short piece, I want readers to have a better understanding of what we do, why we do it and which patients benefit from physiotherapy and how.

I specialise in neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) physiotherapy – previously called ‘orthopaedic physiotherapy’, a term now usually reserved for my hospital-based orthopaedic colleagues. Some of the most valuable and educational experiences I have had in my career are those in which I had the opportunity to work in close collaboration with my medical and surgical colleagues. Unfortunately, clinicians are usually sequestered from each other and so these enriching interchanges happen all too rarely.

While it is difficult for us to work simultaneously in the same room, with patients, it is desirable to work in concert to achieve better outcomes for patients. Chronic aches and pains and recurrent musculoskeletal complaints, for example, can be very frustrating for GPs.

But more and more doctors are achieving beneficial outcomes for their patients by prescribing successful physiotherapy treatment. But what happens to your patient at the physiotherapy clinic – especially at that all important first visit?

Inform – explain – reassure – ‘reduce the threat’

While we have known for some time that patients benefit from being better informed,1-6 patients are often dissatisfied with the information they receive7-9 and many doctors simply do not have the time to provide as much information and education as they would like.10 Physiotherapists are fortunate in that they have more time to do this than a doctor in a busy general practice.

Patients are often confused about their ‘injury’, misinformed by the media and the internet and frightened by the horror stories enthusiastically retold by friends and family.11 Many are anxious or even alarmed by their diagnosis or their MRI results, which seem to suggest their body is ‘disintegrating’ (a word patients frequently substitute for ‘degenerating’).

Pain scientists tell us that the more a patient perceives the injury as a ‘threat’ to them (as an organism), the more pain they are likely to experience, and that negative thoughts and emotions encourage fear avoidance behaviour and promote disability.12 These patients are ideal for physiotherapy intervention.

Even if treatment consists solely of education about the diagnosis, the pathology and the prognosis and teaching simple self-management strategies to avoid recurrence and chronicity, it is clinically valuable: they can benefit from this information for the rest of their lives. Simple self-management strategies include protection of injured tissue and home programmes for strengthening or stretching of dysfunctional muscles.

Assess – diagnose – hypothesise – hone

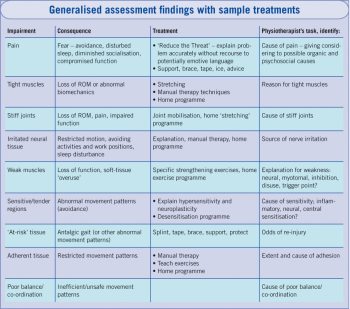

The physiotherapist assesses the patient during the first visit. During the assessment a comprehensive history is taken, followed by a detailed physical examination. Assessment is aimed at identifying patients’ physical impairments and functional deficits and finding their causes: treatment aims to address the causes.

Common impairments include: poor alignment (posture); weak, tight, overactive, atrophied or injured muscles; irritated nerves and hypersensitive regions; problems doing a movement or task; poor balance; stiff joints; instability (‘giving way’, laxity) and even deleterious beliefs, cognitions and behaviours. The most common complaint is pain.

The physiotherapist uses this information (particularly the list of impairments) to develop a ‘best-fit’ hypothesis for the cause of the patient’s problem and this in turn provides a rational framework for physiotherapy treatment.

Assessments of experienced clinicians are more robust because they usually feature tests and procedures specifically aimed at falsifying or at least stressing emerging causative hypotheses. As in other clinical fields, assessment, hypothesis generation, exercise prescription and treatment are increasingly evidence-informed.

While it is a relatively simple matter to identify the proximate cause of many NMS conditions – the patient may have fallen, lifted a heavy load, done unaccustomed physical exercise or been the victim of a physical assault – other patients present months or even years after the natural ‘healing time’ for their injury has passed.

The physiotherapist tries to find out why, for these particular patients, nature has not taken its course and resolved the problem: ultimate causes are sought. This is why a patient, sent to a physiotherapist with, for example ‘wrist pain’ or ‘de Quervain’s tenosynovitis’, may have treatment solely directed at the cervical spine, while another with ‘Trochanteric bursitis’ or ‘ITB syndrome’ may be successfully treated with biomechanical foot orthoses or targeted strengthening exercises for the hip lateral rotators, without having specific treatment for the symptom-generating tissue. The medical diagnosis is not being ignored: the putative ultimate cause of symptoms is being addressed.

While specific interventions, such as joint manipulation, dry needling, stretching, strengthening and ‘stabilisation’ exercises, support bracing, explanation and education, are aimed at the cause of patients’ impairments and functional deficits, treatments also serve as empirical tests of the therapist’s hypothesis. Changes in a patient’s condition can be seen very soon (seconds to hours) after treatment and the causative hypothesis, empirically supported (or undermined) by these responses, is honed accordingly. In this dynamic feedback process, subsequent treatments are directed by improved versions of the causative hypothesis, versions that the physiotherapist has refined after observing responses to treatment. Hypotheses that are strongly undermined by outcomes are discarded – sometimes a follow-up assessment is needed.

A simplified hypothesis-honing process might look like this: A patient presents with restricted motion in the shoulder region and pain of insidious onset. The physiotherapist finds tenderness and restricted accessory motion (‘joint-play’) in the cervical spine.

A possible initial hypothesis that the neck dysfunction is causing the shoulder problem and that the patient’s pain is referred pain, is tested by treating the neck. If manual therapy to the neck improves cervical ‘joint-play’ but the pain and dysfunction remains unchanged, the hypothesis may need re-drafting.

Who can benefit from physiotherapy?

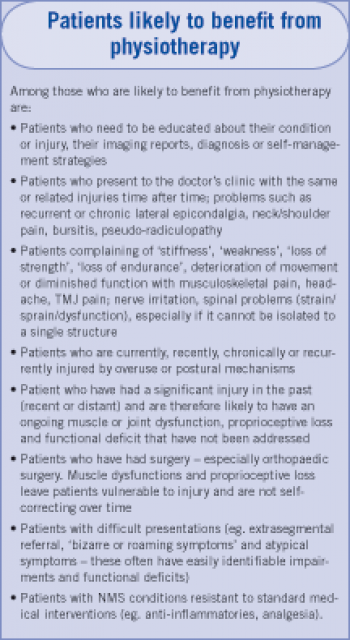

Injured patients are the most obvious category who can benefit from physiotherapy, eg. fracture, dislocation, contusion, sprain, strain or joint derangement. Acutely injured patients benefit from not only early treatment and assessment, but re-assurance, explanation, advice and education about self-management and prevention of recurrence and chronicity.

Patients should not wait until pain, swelling or incapacity ‘settle down’ before consulting a physiotherapist. Many patients wait in vain, sometimes for years, for problems like these to settle down only to finally present with very challenging chronic conditions or widespread pain.

One cannot assume that impairment of muscle function spontaneously resolves once the initial pain or injury is gone. Physiotherapists routinely encounter patients with functionally significant muscle dysfunctions years after initial injuries are ‘healed’.

Human beings display a bewildering repertoire of compensations and thus general activity does not address muscle and joint dysfunctions which can persist despite an apparent return to ‘normal’ activity, range of motion or even ‘strength’.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)