MENTAL HEALTH

DIABETES

Depression and diabetes – the evil twins?

A review of current research on the link between depressive disorders and diabetes

June 24, 2016

-

Recently, there has been an appreciable interest in the psychological wellbeing of people with diabetes. Those with depressive disorders have an increased risk of developing diabetes.1 Despite the huge impact of the co-existence of depression with diabetes on an individual and its enormous importance as a public health problem, there are unanswered questions as to the nature of the link, causes, consequences and possible management of these two conditions.

Epidemiology of depression and diabetes

In people with diabetes, the prevalence of clinically relevant depressive disorders is up to one third.2,3,4 The prognosis of both diabetes and depression is worse when the two diseases are comorbid than when they occur separately.5,6 Rates of depression are particularly high in patients with type 2 diabetes with less evidence for type 1.4

There is a variation in the prevalence rates of depression across Europe but it is consistently higher in people with diabetes compared to those without.7,8 Possible confounding factors in this variation may be a reflection of differences in socioeconomic, environmental and cultural factors and variation in assessment methods. The frequency of recurrence and duration of episodes of depression tend to be higher in patients with diabetes.9,10,11 The risk factors for depression in diabetes can be divided into two12,13:

• Non-diabetes-specific risk factors which include female gender, lack of social supports, low socio-economic status and critical life events

• Diabetes-specific risk factors which include poor glycaemic control, late complications of diabetes, need for insulin in type 2 and hypoglycaemic episodes

Depression is associated with poorer outcomes for diabetes and evidence suggests that poor self-care in depression leads to poor glycaemic control, along with the increased use of health services.14,15 There is a three-fold risk of mortality caused by depressive episodes in diabetes, which was demonstrated in a UK study.16 The Pathways study in the US showed a 1.67 and 2.30-fold increase in mortality.17 The US National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) compared people with diabetes and depression to diabetics without depression and people without diabetes and showed a 2.50-fold increase in mortality over an eight year follow-up study. It has also been shown that people with depressive disorders have an increased risk of developing diabetes.1,18

Pathogenesis of depression-diabetes link

The psychological model

The psychological model has been the traditional explanation for the association between depression and diabetes in that the emotional and practical burden related to

diabetes care leads to depression. In other words, depression is caused by diabetes. This is however, not supported by any literature.16,17 Also, at present there is very little evidence that treating only depression improves glycaemic control, although it does improve mood. There are arguments that the direction of association is reversed or

bidirectional.18,19Depression and insulin resistance

The diabetes spectrum ranges from insulin resistance to impaired glucose tolerance and frank diabetes due to failure of secretion of insulin. Insulin resistance is defined as reduced sensitivity of receptors to the available insulin and it can be peripheral or central. Insulin resistance is a determinant in availability of free fatty acids in blood which are needed for tryptophan and serotonin concentration in the brain. Finnish, Dutch and Chinese studies showed a positive correlation between depression and insulin resistance.20,21,22 However, the major limitation to these studies was the utilisation of self-report depression which may have inadvertently classified symptoms of undiagnosed diabetes as depressive. There was a Japanese case-control study which showed improvement in insulin resistance in depressed patients with antidepressant treatment.23

Depression and HPA axis

The HPA axis is activated by stress and this leads to a cascade of reactions that returns the body to a homeostatic state. First of all, CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone) is released onto the pituitary receptors which leads to the secretion of corticotropin into plasma and ultimately results in cortisol secretion into the blood. This inhibits the gonadal, growth hormone and thyroid axes and at certain levels activates the inflammatory response. The HPA axis also activates the sympathetic nervous system, which increases catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), stimulates the immune response and increases cognitive functioning. The collective metabolic effects are gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis and insulin resistance.24 There is substantial evidence that cortisol and CRH are involved in depression as high levels of cortisol have been observed in depressed patients.25,26,27,28

Diabetes-depression link and the ANS

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems which function in opposition to each other to preserve the dynamic balance of the body’s vital functions. The sympathetic nervous system increases the heart rate, ventilation and causes dilatation of the bronchi. It releases adrenaline and noradrenaline. The parasympathetic system on the other hand, slows the ventilatory rhythm and causes contraction of the bronchi using acetylcholine as its neurotransmitter. In stressful states, the HPA activates the SNS and causes the immediate anxiety response. Irregular sympathetic tone may result from excessive or persistent activation which in turn may lead to dysfunction in metabolic parameters.

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a measure of cardiac vagal tone and also serves as a sensitive indicator of how well the CNS controls the ANS. There is an established link between HRV and depression as decreased levels of HRV are known to be associated with depression.29,30,31 It has also been suggested that acute alterations in the cardiac autonomic tone may be responsible for the increased risk of CAD events and mortality in patients with depression.32,33 However, it is yet to be clarified whether HRV can serve as a clinical predictor of worse depression. There may be a plausible link between depression and diabetes mediated through ANS, although very limited literature is available to support this.

Diabetes-depression link and innate inflammatory response

A biologically plausible hypothesis known as the ‘macrophage theory of depression’34 says that depression is associated with a cytokine-induced acute phase response. The latter is postulated in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and its associated clinical and biochemical features.35 The acute phase response leads to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines which are associated with pancreatic beta cells apoptosis, reduced insulin secretion and insulin resistance with onset of type 2 diabetes. There is growing evidence that stress and depression are associated with acute phase response.36

Genetics of the diabetes-depression link

There appear to be genetic traits in both type 2 diabetes and major depression which aggregate in families due to a complex interaction between the environment and genetic risk.37 To date, little research has been carried out to investigate the direct link between depression and diabetes. Due to the human genome sequencing project which has increased the understanding of patterns of sequence variation, it is now possible to carry out genome-wide surveys of common variant associations and to assess the combined genetic risk for common complex traits such as depression and diabetes.

Diabetes-depression link and birth weight

Since the unravelling of the foetal origins of adult disease in the early 1990s, there is some evidence to suggest a relationship between birth weight and type 2 diabetes later in life.38 There is some evidence, though weak, to suggest a link between low birth weight and depression in later life.39 It is however, yet to be determined whether overweight babies have increased risk for depression.

Diabetes-depression link and early childhood adversity

While a systematic review was consistent for the adverse impact of the accumulation of negative socioeconomic status for CAD risk, the same has not been found to be true for diabetes.40 An important factor for later life depression–diabetes comorbidity may be educational attainment in childhood.41 In a birth cohort study which was followed up to age 32 years, it was found that children who suffered maltreatment showed a significant and dose response increase in CRP levels by 80%, independent of health behaviours in adult life.42,43 Unfortunately, there are no studies to date which compare the risk factors for diabetes and depression over the life course in the same sample.

Diabetes-depression link and the role of antidepressants

Antidepressants have an important role in aiding the understanding of the pathogenesis of the depression-diabetes link. Anecdotal evidence and a small number of randomised controlled trials show that MAOIs and TCAs have a hyperglycaemic effect, while SSRIs (especially fluoxetine and sertraline) are anorectic, improve insulin sensitivity and reduce glucose levels. Partial evidence does exist that treatment of depression with antidepressants does improve insulin resistance and possibly weight loss.44,45,46

On the other hand, there is negative evidence from the US Diabetes Prevention Program for antidepressants.47 A small proportion of sample self-reported use of antidepressants had a two to three fold rise in diabetes risk in those randomised to placebo and to the lifestyle intervention. There was no observed increased risk in the metformin group with antidepressants.47 Antidepressants may also have an immunomodulating effect which has been observed in animal models. This has a positive effect on glucose metabolism.48

Practical considerations

In a large meta-analysis conducted by Anderson et al in 2001, the prevalence of depression in people with

diabetes was 11% while the prevalence of depression that was clinically relevant was 31%.49 Worldwide estimates of depression prevalence among people with diabetes vary by diabetes type and also in developed and developing countries.Depression and diabetes symptoms overlap, hence the patient and clinician may be unaware of depression and may primarily attribute the changed status to worsening diabetes self-care. Secondly, depression may be associated with onset or amplification of physical symptoms in which case the patient may not sense that they are fully understood or supported by their clinician during health care visits when the physical or laboratory results do not correspond to subjective complaints. Thirdly, depression is commonly associated with difficulties with diabetes self-management and treatment adherence.

The patient may feel resigned about their lack of ability to make changes. The clinician may feel discouraged about the ability of the patient to make the relevant changes in their care. Fourthly, individuals with depression may attempt to regulate emotions with food and substances and the clinician is not able to understand the underlying depressive symptoms and the patient’s desperation to regulate emotional pain may come across as judgmental.

Next is the problem of stressors which impact both on the patient and clinician who may attribute poor diabetes outcomes to a decrease in self-management because of a busy lifestyle, but who may not appreciate the insidious development of depression and its consequences.

Depression is commonly associated with changes in healthcare-seeking patterns and following through with appointments. The patient may be reluctant to make appointments, show up for appointments, seek support or collaborate with healthcare providers during appointments.

Another problem is that depression may be associated with poor blood glucose control irrespective of behavioural actions. This may lead to a decreased sense of control of illness and may influence the motivation of the patient to engage in further clinical treatment recommendations. Depression is also commonly associated with difficulty organising tasks; hence clinical instructions may need to be written, repeated and checked for comprehension while the patient is depressed.

Also, depression leads to a more pessimistic view of the future. Thus, clinicians may need to help depressed patients break down tasks into manageable action steps that may have shorter-term pay-off (eg. reduction of physical symptoms). Clinicians also need to consider the presence of anxiety which heightens a patient’s uncertainty around decision-making and increases a general sense of dread about the likelihood of success.

Management guidelines

In a review, Gilbody et al50 found that screening for depression is effective only if aimed to find patients with sufficient severity of depressive symptoms that warrant treatment and if the appropriate treatment is subsequently offered as a result of the outcome of the screening.

Several systematic reviews have been completed evaluating effect sizes of pharmacological treatments in patients with comorbid depression and diabetes. The results of a systematic review of efficacy trials showed that sertraline improved depression with increased time to recurrence; however glycaemic control was poor. It showed a lower HbA1c when patients were depression-free.51,52,53,54

Escitalopram was shown to reduce the depression ratings and improve glycaemic control.55 Depression and anxiety as well as glycaemic control improved with paroxetine.56,57,58

Fluoxetine showed conflicting data in adolescents but it was shown to improve the severity of depression and anxiety and reduced HbA1c levels.59,60,61,62 Bupropion improved the severity of depression, glycaemic control and BMI as well as diabetes self-care.63 MAOIs reduced blood glucose levels; however they can potentiate hypoglycaemia because of their interaction with sulphonylureas.64,65 Last but not least, nortriptyline and amitriptyline were shown to improve depression but had a negative impact on glycaemic control. There was possible interaction with sulphonylureas thereby causing symptomatic hypoglycaemia and possibly hypoglycaemic unawareness. The efficacy trials ranged from two weeks to three years. The choice of antidepressant medication for the patient with depression and diabetes remains one in which the clinician needs to tailor the therapy to suit the specific needs of the individual.

Studies in support of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) varied from 10-24 weeks duration of study and it showed reduced severity and increased remission rates for depression as well as improved glycaemic control.67,68 Because depressed patients with diabetes more often have an increased severity and high rate of recurrence of depression, the healthcare provider will often find that the medication course is more prolonged and the use of the behavioural therapies is more crucial. There needs to be a more comprehensive approach to improve both psychiatric and medical outcomes, which includes both evidence-based depression treatment and interventions aimed at improving diabetes self-care and glucose control.

There is an association between ineffective provider-patient collaboration and lower levels of trust, poor information exchange and decreased satisfaction. The latter may lead to poorer adherence and poorer clinical outcomes.69

Successful management of both conditions requires intensification of efforts in the therapy of depression and medical therapy of diabetes as well as a much higher level of prolonged cooperation between different disciplines for optimal results for the patient.

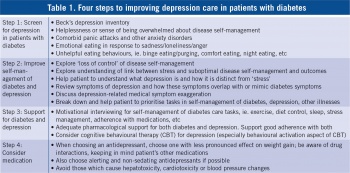

In summary, active screening for depression in patients with diabetes should be carried out. Emphasis should be on improved self-management of both illnesses and there should be adequate support from clinician/team, both pharmacologically and psychologically.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)