NEUROLOGY

Unpredictability of motor symptoms in Parkinson's Disease

Parkinson’s disease is an individual and fluctuating condition with symptoms varying and changing at any time

March 1, 2013

-

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic progressive neurological condition caused by the degeneration of dopamine-producing nerve cells in the substantia nigra, which is located within the basal ganglia deep in the lower region of the brain, on either side of the brain stem. This area in the brain is where programmes of movement are stored adjusted and initiated.

By the time Parkinson’s disease symptoms are evident, up to 80% of dopamine may already have been lost from nerve cells in this part of the brain. Its prevalence in Europe is around 160 per 100,000 in the general population. Statistically, men are slightly more likely to develop the condition than women. The risk of developing Parkinson’s disease increases with age, and the symptoms often occur after the age of 50. Some people may not be diagnosed until they are in their 70s or 80s, however in some cases Parkinson’s disease is diagnosed before the age of 40 and this is known as young-onset Parkinson’s disease. If it is diagnosed before the age of 18 it is known as juvenile Parkinson’s although this is extremely rare.

The cause of Parkinson’s disease is unclear and no cure is available. Aging is linked to the disease but not solely responsible. Most researches believe that multiple factors play a role in causing Parkinson’s disease and that it is likely to be caused by a combination of both genetic and environmental factors.

Early diagnosis is essential but can be difficult. There are no consistently reliable laboratory tests or easily available imaging tests available that can distinguish Parkinson’s disease from other conditions that have similar clinical presentations. While single proton emission CT (SPECT) scanning may assist in making the diagnosis, this is only available in some centres. It is more likely to be used to exclude other conditions that may have similar symptoms.

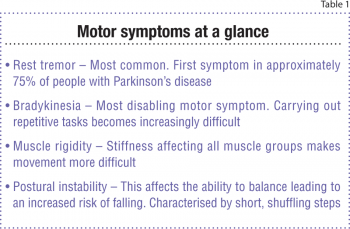

If the diagnosis is suspected a patient should be quickly referred – untreated – to a neurologist or a geriatrician with a special interest in Parkinson’s. The NICE guideline on the diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease says referral time should be no more than six weeks. The diagnosis is primarily clinical following a detailed history and examination. People with Parkinson’s disease classically present with four cardinal motor symptoms – rest tremor, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), muscle rigidity (stiffness) and postural instability. Parkinson’s disease usually presents with unilateral symptoms that eventually progress to bilateral involvement, although the side of the symptom onset usually remains the more severely affected in the course of the disease.

Medication is the first option of treatment and neurosurgery may be indicated for advanced disease or drug-induced complications. Other treatments such as occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech and language therapy can also be effective in controlling and managing symptoms.

Motor symptoms

Rest tremor

This is the most common visible motor sign that leads one to seek medical advice. It is the first symptom in about 75% of people with Parkinson’s but up to 20% never develop tremor at any stage. It usually affects the hands and arms and sometimes the legs. Tremor may also affect the lips, lower chin, tongue or face, though these often occur in the later stages of Parkinson’s disease.

It classically disappears during action or when asleep. This is known as a resting tremor. In the hands it is sometimes referred to as ‘pill rolling’ tremor, as it involves the thumb and index finger in a rolling movement. Occasionally tremor is not noticeable to others but can be felt by the person with Parkinson’s disease internally. It is aggravated by emotional stress, anxiety and fatigue. It can be very embarrassing and is considered a major problem for some people limiting social interaction.

Bradykinesia

Slowness of movement is insidious and may be initially mistaken for normal aging, the effects of arthritis, or even depression. Bradykinesia is a slowed ability to start and continue movement and is often the most disabling motor symptom of the condition. Fine movement is affected first, eg. doing up buttons and handwriting, before the affected person notices they take longer to start and carry out activities such as walking, getting out of chairs, dressing and eating. In addition carrying out a series of movements and doing repetitive tasks can become very difficult and tiresome.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)