CHILD HEALTH

PAIN

Child-friendly aids in pain management

It is important to be familiar with a range of child-friendly pain management aids in order to choose one that best meets the needs of the client

July 1, 2012

-

Children who present to hospital frequently encounter medical procedures that are painful, unexpected and frightening. These procedures are worsened by the stress and anxiety caused by unfamiliar surroundings and this leads to poor experiences of healthcare settings.

The principles of pain management apply to all; however, infants and children pose unique challenges to nurses that require consideration of a number of factors, including: the child’s age, developmental level, communication skills, cognition, previous experience of pain and associated beliefs.

Perception of pain in children is complex and involves physiological, psychological, behavioural and developmental factors.¹ Despite this, pain in infants and children is frequently under-estimated and under-treated. It has been found that infants and children who experience pain in early years, show long-term changes in terms of pain perception and related behaviours.²

In 2007, a total of 144,703 children aged between 0-17 years were discharged from hospital in Ireland.³ Common procedures that children undergo while hospitalised include venepunctures, wound dressings, lumbar punctures and urinary catheterisation. Many pain assessment tools and child-friendly aids are available to nurses to assess and ease children’s experiences of what is frequently frightening and foreign in a child’s life. This article focuses on those used with neonates, infants and school-aged children.

Tool selection

Selection of an appropriate pain assessment tool is influenced by a number of key factors that nurses need to be cognisant of. These include: age group; the clinical setting in which the tool is being used; the cultural appropriateness and language of the tool; whether the tool has been designed for use by the child, nurse or parent; and any training and educational requirements needed to deliver the tool.4

As a general rule, tools designed to be observer-rated should not be used as self-report tools and vice versa. A number of studies that compared children’s scores on a self-report scale to observer-rating with the same tool found that professionals consistently record lower pain than children. Meanwhile, parents’ scores correlated well with their children’s scores.5-7

The accurate clinical assessment of pain relies on a multitude of formats, including self-reporting, behaviour observational pain scales and physiologic measures of pain. Self-reporting relies on the cognitive ability of the child to effectively convey their discomfort. Neonates express pain through crying and physical gestures. Toddlers begin to articulate words for pain by about 18 months of age, and by age three to four years they are more able to accurately report degrees of pain, which supports the use of a combination of physiologic and observational scales.

Self-reporting and physiological or observational scales are effective in older children (five to seven years-of-age) who exhibit improved understanding of pain and are more able to localise pain and cooperate with healthcare professionals. As a rule, school-aged children without any neurological deficits can start using the standard adult pain assessment scales around the age of seven to eight years.8

Pain assessment tools for neonates and infants

As neonates cannot self-report, pain assessment tools for use in this age category should ideally include a composite of measures. For example, the measurement of facial response to painful stimuli and physiological response. Tools in this category are observer-rated and will require the user to undergo training in their appropriate use and interpretation of neonate responses.

The majority of pain assessment tools in this category have been validated in post-operative settings with some validated following procedures such as catheter insertion, routine heel stick and endotracheal intubation. Examples of scales include COMFORT, Cries, Neonatal Facial Coding System (NFCS), Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS), Objective Pain Scale (OPS), Pain Assessment Tool (PAT) and Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP).4

Pain assessment tools for children

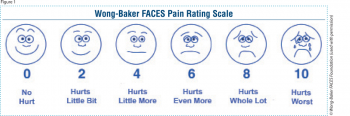

For verbal children, self-report is considered to be the most valid measure of pain intensity. Face scales such as OUCHER, Wong-Baker FACES (see Figure 1) and the FACES Pain Scale are cognitively appropriate for children aged between three and seven years and who have the ability to quantify abstract phenomena.9

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)