CHILD HEALTH

NUTRITION

Managing fussy eating in toddlers

Appropriate parental response to fussy eaters can minimise negative effects on both the child’s heath and the parents’ psychological well-being

December 20, 2013

-

Fussy eating is common in toddlers. Most toddlers go through phases of refusing to eat certain foods or at times, refusing to eat anything at all. Fussy eating and food refusal are normal developmental stages. The former can be a means for a toddler to demonstrate independence and it is suggested that food refusal (or food neophobia, which is a fear of new foods) is an innate safety mechanism to protect the toddler from ingesting a toxic substance.

The effects of fussy eating largely depend on its duration. When managed appropriately it is a short-lived phase that does not lead to nutritional deficiencies or other health consequences. However if not managed correctly, fussy eating and thus poor diet, can persist and the child’s health may be at risk. Some studies show that picky eaters weigh less than their peers. However more significantly, there is evidence that a poor diet in childhood predicts poor diet in adulthood, which increases likelihood of otherwise preventable conditions such as obesity, cancer and heart disease.

Fussy eating can be a significant cause of worry, anxiety and conflict for parents. Inappropriate parental response to fussy eating is often counter-productive and may exacerbate and perpetuate the phase, thus increasing risk of long-term health problems for the child.

Just a phase?

The prevalence of feeding problems in infants and toddlers as reported by their carers is approximately 25-40%.1 A significant proportion of referrals to paediatric dietetic clinics is for young children who are eating a very limited range of foods.

Fussy eating is a normal developmental stage, but is also seen in various developmental or clinical conditions. It may be the cited reason for referral for children presenting with more significant and severe feeding issues arising from problems such as autistic spectrum disorder, pain or discomfort from an underlying medical condition, immature swallowing skills, sensory processing deficits, cognitive delays or nutritional disorders.

It is important to distinguish between fussy eating and a more serious feeding problem. In general, children going through normal fussy-eating phases, despite parental reports, will actually be consuming at least 20, and often more than 30 different foods. They generally will be consuming some foods from each nutritional group and also from each texture group. ‘Refused’ foods can usually be presented without causing distress, and the child will probably interact with these foods though may not bring the food to his or her mouth.

Children who are fussy eaters, as opposed to having a more severe feeding problem, will usually be of normal weight and have normal growth and development. A full nutritional assessment by a paediatric dietitian or a feeding assessment by a multidisciplinary team at a feeding clinic will determine whether the fussy eating habits are due to the normal developmental phase or a more serious issue that requires further investigation and input.

Managing fussy eaters

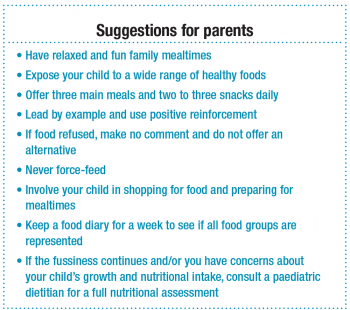

For effective management of fussy eating to minimise its duration, and therefore reduce the risk of long-term health problems and reduce parental anxiety, the following should be considered:

What’s on offer?

During phases of fussy eating, children should continue to be offered a normal, balanced age-appropriate diet and should not be filling up on inappropriate foods and drinks. Anecdotally, a very large proportion of children presenting to dietetic clinics as fussy eaters are drinking inappropriate drinks. Milk and water are the only drinks that children need. For more information, see the factsheet, ‘Drinks for Preschool Children’ at www.indi.ie).

‘Normal’ toddler appetite

In the first two years of life, growth rates are rapid. From age two, growth velocity naturally slows down and often appetite decreases to match this. This decline in intake can provoke anxiety in parents despite it being a normal physiological phenomenon. In addition, toddlers tend to have erratic appetites, varying from meal to meal and from day to day. However despite highly variable intakes, healthy children have a remarkable capacity to meet energy needs over time when offered an assortment of nutritious foods.

Meal and snack routine

Young children need to eat little and often to meet nutritional requirements and so should be offered three main meals and two to three snacks, daily. Allowing constant grazing interferes with the development of normal appetite recognition and actually results in lower nutrient intake compared with scheduled meals and snacks.

Consistent response

The fussy eater should get the same response from each parent or carer to ensure the child is getting consistent messages. This consistency should be extended to all care settings for the child (eg. childminder, crèche, grandparents, etc).

How much?

Toddlers need toddler-size portions. Small meals and snacks should be presented. One tablespoon of food per year of age can be an approximate starting point.2 Second helpings can then be given if the toddler requests it.

Children should not be made finish their food as this has been shown to tamper with appetite recognition and later increase likelihood of excessive eating and overweight. Children do have innate intake control and so should be allowed to eat to appetite.

‘Sensory-specific satiety’ refers to how the desire to eat a meal reduces as the meal is consumed. So it is perfectly normal to have enough of a savoury main course but then to ‘have enough room’ for the yoghurt or fruit course that follows.

The parent or carer should decide what food is to be served at each meal, the toddler decides how much to eat. Multiple choices or alternatives for food refused are not recommended. Parents may opt to always include at least some ‘liked’ food within the meal to ensure at least something is consumed. Two courses can be offered at main meals, within the context of healthy eating, and the second course should not be contingent on the first course being eaten.

Role modelling

Just as young animals only eat foods eaten by their parents, the same holds true for humans. Parents set the example and blueprint for what is acceptable, normal and safe to eat. Parents need to be positive role models by consuming a balanced healthy diet. This can be reinforced verbally by discussing the properties of foods at a level appropriate to the child’s ability (eg. remark on the different colours, tastes and textures, or for older children on the health benefits).

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)