DIABETES

Managing recent onset type 2 diabetes

A case study illustrates how lifestyle modification is the first step towards control of blood pressure, obesity and abnormal lipid levels

December 1, 2011

-

A 63-year-old man comes to the practice as a new patient. He works as a lab technician and has no complaints other than an 8kg weight gain over the past two years. He was widowed during this time, and as a result eats most of his evening meals in restaurants. He drives to work every day and has no established activity programme. He spends most evenings watching TV or surfing the internet. He has two grown daughters who live nearby.

On physical exam, his height is 175cm and weight 95kg. His body mass index (BMI) is 31. His blood pressure (BP) is 154/90mmHg.

The remainder of his exam is notable only for abdominal obesity and a decreased right pedal pulse. He stopped smoking 10 years ago and has one glass of wine with dinner most nights of the week. He takes an occasional over-the-counter antacid for heartburn and a non-sedating antihistamine for springtime allergies.

He has positive family history for type 2 diabetes in both parents. His father had a heart attack at age 62 with subsequent coronary artery bypass graft surgery. His mother has osteoporosis; his children are both alive and well.

On further discussion, he believes that his weight gain is related to the change in his lifestyle. In the past, his wife cooked most of their meals and tried to ‘make them nutritious’. His daughters frequently invite him for dinner, but he typically declines so as ‘not to be a burden’. They are worried about his health and whether ‘he is taking care of himself’.

His blood biochemistry revealed that after an eight-hour fast, his fasting blood sugar (FBS) was 7.8mmol/l on initial evaluation and 7.7mmol/l on re-evaluation, indicating type 2 diabetes. High-density lipoproteins (HDL): 0.9mmol/l;

low-density lipoproteins (LDL): 3.8mmol/l; TG: 1.5 mmol/l.Discussion

Lifestyle modification is the first step in controlling blood pressure, obesity, and abnormal lipid levels. Evidence now demonstrates that changes in lifestyle, such as diet and physical activity, can prevent or delay diabetes and its complications.1,2 People with diabetes should be advised to perform at least 150min/week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity (50-70% of maximum heart rate).3 Cardiovascular risk factors – such as plasma triglycerides, LDL, HDL, blood pressure, and obesity – should all be addressed in order to reduce complications of diabetes as well as cardiovascular events.4

What is his target BP goal?

Hypertension is arguably the strongest cardiovascular risk factor. Patients with blood pressure greater than 140/90 should initiate antihypertensive therapy along with lifestyle measures.4 First-line antihypertensive measures include an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), possibly along with a diuretic. It is not unusual for patients to require two or more agents to control their blood pressure.

After a frank discussion about his risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, the patient expresses a desire to begin a trial of lifestyle changes prior to beginning any diabetes medication. He is advised to start a moderate walking programme and that he begin to join his daughters for dinner at least twice a week. He is also recommended that he and his daughter make an appointment to see a dietitian. He is prescribed the following medications: simvastatin 20mg daily; losartan/HCTZ 100/12.5mg daily; ASA 75mg daily. He is asked to return in two months.

On his return visit, he has lost 3.5kg. His weight is now 91kg (BMI 29.7); BP 126/74mmHg. He is taking medications as prescribed and is participating in a walking group at work two mornings per week. He is eating dinner with his daughters two nights per week and they are preparing foods for him to eat at home and at work.

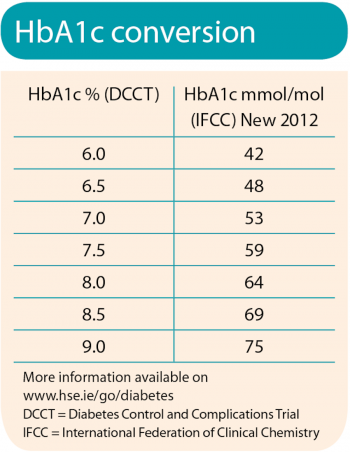

Labs on return visit were: HbA1c: 7.6%; LDL: 2.46mmol/l; TG: 1.5mmol/l.

What are his target lipids?

According to the Standard of Care published by the American Diabetes Association (ADA),4 reduction of A1c to ≤ 7% has been shown to reduce microvascular and neuropathic complications of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The ADA-recommended goal for LDL is < 2.5mmol/l, with a triglyceride goal of < 1.7mmol/l.4

Managing hyperglycaemia

The patient agrees that despite his efforts, he has not achieved optimal glycaemic control and agrees to begin medication to treat his diabetes.

All approved oral agents lower HbA1c to some extent. Although there is no one ideal agent, the ADA Consensus Statement on the Approach to Management of Hyperglycaemia9 recommends the use of metformin in combination with lifestyle changes at the time of diagnosis. Metformin improves glycaemic control by inhibiting gluconeogenesis and increasing insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Gastrointestinal side-effects include loose stools and diarrhoea. No hypoglycaemia or weight gain is typically noted when metformin is used as monotherapy.8

Exenatide and liraglutide are both associated with GLP-1, a protein that slows glucose absorption from the gut, increases insulin secretion when the blood sugar is high, and reduces glucagon levels after meals.

As incretin mimetics, they stimulate insulin secretion, suppress glucagon secretion, and slow gastric motility. The most common complaint for both drugs is the development of gastrointestinal side-effects, such as of nausea, vomiting, or diarrhoea.9 Exenatide is administered subcutaneously twice a day and is not approved for monotherapy. Liraglutide is administered subcutaneously once a day, at any time.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)