WOMEN’S HEALTH

Mastitis – a guide to diagnosis and management

Optimal breastfeeding management is important to prevent the occurrence of both non-infective and infective mastitis

December 1, 2017

-

Mastitis is a tender, hot, swollen, wedge-shaped area of breast associated with pyrexia, flu-like aching and systemic illness. However, ‘mastitis literally means, and is defined herein, as an inflammation of the breast; this inflammation may or may not involve a bacterial infection’.1 Mastitis can be non-infective or infective.2

Non-infective and infective mastitis

Non-infective mastitis, where the symptoms of heat, redness and soreness in an area of the breast present, may arise from milk stasis due to poor removal, sudden changes in the baby’s feeding pattern, trauma and from pressure of clothing or pressure from holding the breast resulting in a plugged or blocked duct.2 The onset is gradual and unilateral, and the mother feels generally well.3

Infective mastitis is caused by infections either in the outer skin of the breast or within the glandular tissue of the breast. If left untreated this may develop to the formation of a breast abscess.2 The incidence of mastitis ranges from 3-20%3

The highest occurrence is generally two to three weeks after the birth of the baby; however, mastitis can occur at any stage during the course of lactation.4

The most common causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus. The infection is usually unilateral and located in one area of the breast, often the upper outer quadrant because much of the breast tissue is located there.2

Risk factors

There are many risk factors that may predispose a mother to developing mastitis including:

- Stress and fatigue

- Poor positioning and attachment of baby to the breast

- Damaged nipples and nipple pain – where there may be breakdown in the dermis which allows a pathway into the breast tissue

- Plugged or blocked ducts.2, 4-8

Diagnosis

A detailed history is required involving a breastfeeding history, pain history, mother’s own history and baby’s history. Examination of the mother’s appearance, nipples and breast is also necessary. Laboratory investigation (breastmilk culture and sensitivity) are not routinely performed unless according World Health Organization guidelines:9

- There is no response to antibiotics within two days

- The mastitis recurs

- It is hospital-acquired mastitis

- The patient is allergic to usual therapeutic antibiotics

- In severe or unusual cases

- There is a suspicion of a breast abscess which may require surgical intervention.

Management

Optimal breastfeeding management is important to prevent the occurrence of both non-infective and infective mastitis. The development of mastitis may be largely preventable through better patient education and practical training.10 Mothers need to be supported to correctly position and attach their baby to the breast and respond to the baby’s early feeding cues. It is the role of the health- care professional to support the breastfeeding mother or if necessary refer the mother to skilled breastfeeding support. Good antenatal breastfeeding education and proper positioning and attachment in the first week after birth would assist in the prevention of nipple damage and subsequent infection.11

Management of non-infective mastitis:

- Good hand hygiene

- Removal of the source of pressure

- Application of moist heat to the breast before the breastfeed

- Frequent and effective milk removal

- Gentle breast massage just behind the sore area, while breastfeeding

- Vary feeding positions by positioning the baby with the chin facing the blockage of the affected breast, which will promote better drainage12

- It is important to be alert for signs of a developing breast infection – fever, chills and aching.12

Management of infective mastitis

Parents and healthcare professionals should practise good hand hygiene as often the causative organism of mastitis is Staphylococcus aureus.

If a breast pump is being used then appropriate care of the attachments and pump, as per hospital or home use guidelines is essential.1

Frequent and effective milk removal is important and if the mother can breastfeed her baby, she should continue to do so starting if possible on the affected breast. If pain interferes with the let-down reflex she can begin on the unaffected breast and change to the affected breast as soon as the breast milk starts releasing.1

The mother can vary feeding positions by positioning the baby with the chin facing the blockage of the affected breast to assist in effective milk removal.1

Removal of residual breastmilk from the affected breast by expressing breastmilk by hand or by pump after the feed may be necessary.8

If breastfeeding is too painful, the mother may use a hospital grade electric breastpump to ensure frequent and effective milk removal.8

Use of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as ibuprofen may be necessary if the mother has a low grade temperature and a painful and aching breast.4

Breast massage should be directed from the blockage moving towards the nipple and performed several times a day. Therapeutic breast massage in lactation (TBML) may be helpful in reducing breast pain associated with milk stasis.13 Application of heat, eg. a shower or hot pack to the breast prior to feeding may help with let-down and milk flow and after the breastfeed or after milk is expressed from the breasts cold packs can be applied to the breast in order to reduce pain and oedema.1

A mother with mastitis should be greatly encouraged and supported to rest and it should be ensured she has adequate fluids and nutrition.

After the resolution of mastitis the affected breast may produce less milk temporarily than before the infection. The mother can increase her milk supply by regular, uninterrupted breastfeeding and contact with her baby.14

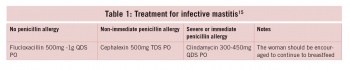

Antibiotic treatment for infective mastitis

Table 1 outlines the treatment for infective mastitis as recommended by Medication Guidelines for Obstetrics and Gynaecology – Antimicrobial Prescribing Guidelines15

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)