CANCER

DENTAL HEALTH

Oral cancer: An overview

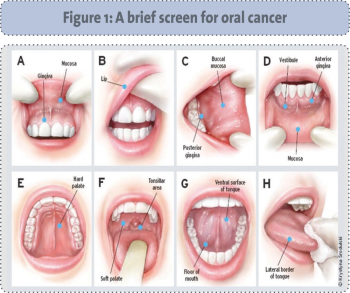

Increased public health initiatives are needed to target any behaviours that increase risk of oral cancer. All healthcare practitioners, including dental and medical practitioners, should be aware of the presenting features of oral cancer

February 1, 2013

-

Over 90% of head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC)1 and include cancers of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, sinonasal tract and the nasopharynx. HNSCC is the sixth most common cancer in the world; almost 600,000 cases are reported annually.2 Approximately five out of every 10 patients with HNSCC present with advanced stage disease.3,4 Oral cancers compromise approximately 85% of the HNSCC population. It is the most common form of cancer in India, and incidence is higher in countries in Latin America than in the United States and northern Europe, with Hungary, France and Scotland identified as having the highest prevalence rates in Europe.5,6 In Ireland, oral cancer represents 4% of all cancer registrations and 1.5% of cancer deaths. This equates to 300 cases and 150 deaths per annum.7 In addition, oral cancer is 2.5 times more common in men than women.8 Historically, the majority of people are over the age of 40 at the time of discovery of an oral cancer symptom but, in the last number of years, it is now occurring more frequently in younger people due to a viral cause, the human papillomavirus 16 (HPV16).

Survival rates and risk factors

Survival rates for head and neck cancers, overall, are poor in comparison to other type of cancers. The five-year survival rate for small tumours of the oral cavity approaches 80% but falls to approximately 30% for advanced disease.2

Traditional risk factors such as tobacco, alcohol and areca (betel) nut chewing continue to be responsible for the majority of all HNSCC.9 Combined use of tobacco and alcohol results in a 15-fold increased risk of developing oral cancer.8 In addition, continued tobacco use increases the incidence of primary recurrence and the development of second primaries.10

However, oral infection by HPV16 is now believed to be the aetiological agent in a subset of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC).11 Specifically, HPV has been shown to be responsible for 40-60% of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) arising from the tonsil or base of tongue.11,12 One hypothesis for this trend is the increasing prevalence of sexually transmitted HPV oral infection in the population.13 Thus, the International Agency for Research against Cancer (IARC) has acknowledged HPV as a risk factor for oral and oropharyngeal cancer.

Smoking, tobacco use and unsafe sexual practices are all preventable risk factors. Increased public health initiatives are needed to target these behaviours. Other risk factors for oral cancer include chronic poor oral hygiene, family history, low socio-economic group, males aged over 65 years, malnutrition (with deficiencies in vitamin A, C and E, iron-deficiency anaemia); occupational exposure to dust, fumes or chemicals and sunlight (lip cancers).

Presenting symptoms and treatment pathways

The main signs and symptoms of oral cancer include a non-healing ulcer or sore, a persistent lump or swelling, a white or red patch in the mouth or difficulty chewing or swallowing.14 White or red patches often indicate a precancerous condition and should be biopsied. Up to 10% of leukoplakias (white patches) indicate cancer cells on biopsy and 50% of erythroplakias (red patches) indicate severe dysplasia or a carcinoma on biopsy.8 Symptom(s) that persists for more than two weeks should be investigated.

The treatment of oral cancer is multifaceted and lengthy due to the surrounding anatomical structures. The goal is to cause as little functional and cosmetic damage as possible.15,16 Curative treatment implies a combination of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. For this reason, a multidisciplinary team (MDT) is now used to improve the overall treatment and outcomes for this group of patients.6

During the hospital treatment period the patient is referred to both medical and dental teams in specialities such as head and neck surgery, plastic surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, radiation oncology and radiation therapy. Advances in reconstructive surgical techniques and dental implant technology have dramatically changed the reconstruction of these defects and patients can now be provided with more reliable means of retaining prostheses. Speech therapists, nutritionists and social workers play important roles in rehabilitation of speech and eating problems after partial removal of the tongue or floor of mouth.17

Clinical staging in head and neck cancers follows the tumour, node, metastasis method (TNM).18 Once the TNM is determined, a tumour stage of I, II, III or IV is given, with stage I cancers typically small, localised and curable. Stage II and III cancers are typically locally advanced and/or have spread to local lymph nodes, and stage IV cancers typically metastatic (have spread to distant parts of the body) and generally considered inoperable with treatment tending to be palliative.

Stages I and II are characterised by a five-year survival rate of 70-90%.2 Stages III and IV have poor prognosis with a survival rate of 20%.2 Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) also has an unpredictable capacity to metastasize to the neck, an event that dramatically worsens prognosis.19 More than 50% of patients with OSCC of the oral cavity have lymph node metastases.20

Lansford et al have found that postoperative alcohol withdrawal management is time-consuming and a challenging process.21 Therefore pretreatment care includes smoking cessation and management of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol misusers have complication rates two to three times higher than patients who drink two units of alcohol a day. These complications rates are associated with 50% longer hospital inpatient stays, infection rates, bleeding, and cardiac insufficiency.22 The main goal of treatment is to guarantee long-term tumour free survival with as little loss of function as possible.23 The combination of treatments has the advantage that the effectiveness of each one can be limited to preserve as much function as possible.

Despite progress in developing these strategies, cancers of the oral cavity continue to have high mortality rates, which have not improved significantly over the past 10 years.24 Semple et al also reveal that the physical consequences of treatments can be evident for prolonged periods and in some cases permanent.25

Chemoradiotherapy

Chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced oral cancers has led to increased local regional control, tissue preservation and survival. However, improved disease-related outcomes are at the expense of increased acute and late toxicities.26 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be used before surgery to shrink the tumour. It can also be used in combination with radiotherapy, acting locally to reduce tumour size and the extent of surgery; at the same time chemotherapy offers the potential of treating metastases. Chemoradiotherapy may be used following surgery, usually three treatment cycles in combination with radical radiotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens for head and neck cancer usually require hospital admission for pre and post hydration to reduce the toxic effect on the kidneys.

Radical curative radiotherapy alone or post-operatively may also be used to treat oral cancer. Radiotherapy planning involves making a plastic head mould to ensure the patient lies in the same position at each treatment. Treatment is usually delivered daily (Monday to Friday) for up to seven weeks. Regimens may differ depending on the cancer centre. A range of chemotherapy regimens may be used in head and neck cancer (including oral cancer). Some patients may start radiation therapy while they are still recovering from the side effects of their surgery.17

Larsson et al demonstrate profound disruption to a patient’s life during chemoradiotherapy treatment due to eating difficulties and associated problems caused by cancer and its treatment.27 Speech, however, appears to be relatively uncompromised.28 Radiation treatment is initially painless. However, during treatment, side effects such as dry mouth (xerostomia) and mucositis may result in difficulties speaking, swallowing and taking in fluids and necessitate hospitalisation to prevent dehydration and malnutrition.

Limiting radiotherapy damage to the salivary glands by restricting the radiation exposure using intensity-modulated radiotherapy may prevent xerostomia and may also diminish adverse late oral health outcomes.

Surgery

Advances in surgical techniques have significantly reduced debilitation and improved functional and cosmetic outcomes for patients.29 Surgery in the mouth includes the partial or complete local resection of the affected area: glossectomy (tongue), maxillectomy (roof of mouth), mandibulectomy (floor of mouth and lower jaw) and excision of salivary glands. Advanced surgical techniques have been developed such as free-tissue transfer (skin/tissue/bone) with blood vessels attached from one area of the body to another, enabling a functionally superior reconstruction of the operative defect at the time of resection.14 This type of reconstruction aims to restore the defect created by the removal of the tumour to as near normal as possible.

The main argument in favour of elective treatment with neck dissection (a safe oncological surgical procedure that significantly reduces the risk of regional recurrences) is strong,19 given the reported incidence of clinically positive neck metastases and occult cervical metastases in tumours of the lower part of the oral cavity.

A selective neck dissection involves the removal of lymph nodes that are first involved in the tumour spread. A radical neck dissection involves the removal of all the lymph nodes in the neck between the jaw and collarbone, along with other associated structures. However, when removal of the sternomastoid muscle, cervical plexus and accessory nerve is necessary, significant postoperative morbidity can occur,14 mainly from reduced shoulder strength, pain and limited movement.

Post treatment

People affected by head and neck cancer experience very distressing and debilitating symptoms throughout their cancer treatment trajectory.30-33 Following treatment for oral cancer, it is clear from the research conducted with patients that there are a number of concerns and challenges that cannot be compartmentalised into unitary or discrete aspects of life. Patients with primary disease often experience significant difficulties in adjusting to life, including the multiple losses and fears associated with the diagnosis and treatments for primary HNSCC.34 Others struggle to cope, finding they feel helpless and that they have lost meaning and purpose in life.25 Support during and after treatment therefore is vital.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)