DIABETES

Proactive improvements to diabetes management

A nurse-led diabetes clinic in a Dublin general practice has reported impressive results

July 1, 2013

-

An estimated 129,052 people in Ireland have adult type 2 diabetes, which is 4.3% of the adult population.1 The cost of this preventable condition to the Irish health service is estimated at e2,468 per patient per annum, two-thirds of which is spent on the management of diabetes complications.2

In Ireland, diabetes care has traditionally been delivered in the hospital setting, however, as the population of people with diabetes increases there is a need for primary care to take on a greater role in managing this chronic condition.3 Most GPs in Ireland report providing high levels of care to their patients with diabetes, particularly type 2; however this is mainly unstructured.4 The purpose of this study is to show the effectiveness of structured care through a nurse-led diabetes clinic and the impact it has on the patients, the practice and the national health service.

Practice diabetes study

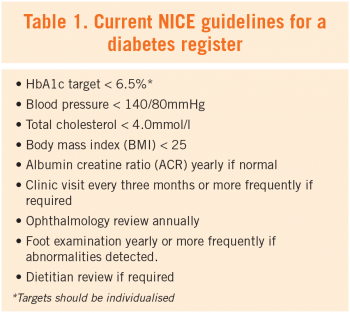

Rialto Medical Centre is situated in Dublin’s south inner-city and serves a largely GMS-based population. An initial audit was undertaken using the practice software (Socrates v1.7), which identified 82 patients with diabetes. The 13 patients who were diagnosed after the study starting point of 2010 were excluded. Data was collected for the 12-month period of 2010-11 on all 69 of the remaining cohort, in accordance with the current National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for a diabetes register, which included patient demographics, modifiable risk factors, medication prescribed, attendance at practice and hospital outpatient review (see Table 1).

The study follow-up period coincided with the establishment of a diabetes clinic, led by a clinical nurse specialist in diabetes and was done on a cost-neutral basis to the practice. All 82 patients identified were formally invited by letter to attend the clinic. For the purpose of this study we are only concerned with the 69 patients who had a diagnosis prior to 2010; of these, 42 (61%) agreed to participate.

Phase 1: Practice Audit (2010-11)

Demographics: The majority of the practice diabetes register was male (52%), aged between 60-79 years (58%) and GMS cardholders (87%). Eight (22%) patients were documented as being a smoker.

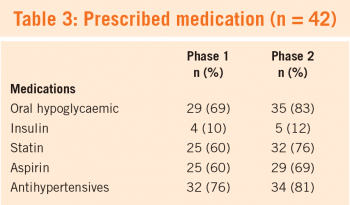

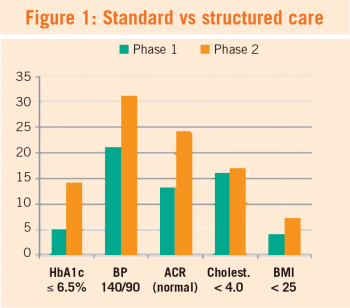

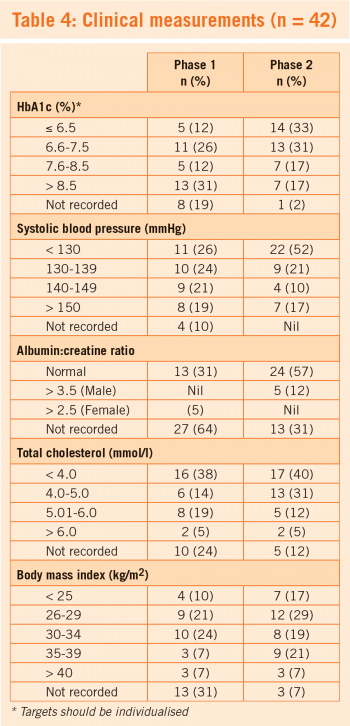

Medical profile: Five patients (12%) had a recorded HbA1c ≤6.5%, 21 (50%) had a blood pressure recording of <140/80mmHg, 13 (31%) had a normal albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR), 16 (38%) had cholesterol <4.0mmol/L, and four (10%) had a body mass index <25.

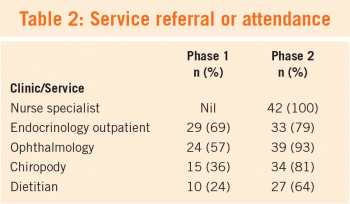

Service usage: Twenty-nine (69%) had attended, or had a referral to, a diabetes outpatient department clinic in the previous 12 months. Twenty-four (57%) had attended, or had a referral to, an ophthalmology clinic. Five patients were admitted to hospital for a diabetes-related problem within the previous 12 months.

Phase 2: Diabetes nurse-led clinic follow-up (2011-12)

A formal invitation by letter was sent to all those identified in the initial audit. Any new diagnoses of diabetes/impaired glucose tolerance are also recruited on a rolling-basis.

One third (33%) of the cohort had a HbA1c of ≤6.5%, in comparison to 12% in the first phase. Systolic blood pressure after one year in the clinic reported over 70% having a recording <140mmHg in line with evidence based guidelines. Documentation of renal function was also much improved, with 57% having a normal ACR and 48% having a recorded estimated glomerular filtration rate >90ml/min/1.73m2.

Some 33 (79%) and 39 (93%) of the patients either attended or were referred to the endocrinology outpatients and ophthalmology services respectively, while 27 patients (64%) had a record of attending, or being referred to, the dietitian and 34 (81%) to podiatry services.

Discussion

The ICGP report (2008) on integrated care of type 2 diabetes patients sets out the three key components to setting up a diabetes register: identification and registration of patients, recall and regular review.5

The development of a practice register establishes a database for quality controlled care and monitoring. One study in 2006 showed that 43% of GPs in Ireland maintained a diabetes register,6 while a similar paper published in 2009 by the Department of Public Health at UCC reported similar figures of 45%.4 However, the National Survey of Chronic Disease Management in Irish General Practice (2011) reports that while the majority of GPs in Ireland use written evidence based guidelines when managing diabetes in their practice, two-thirds rarely or never use a tracking system to remind diabetes patients about needed visits.7

Our practice diabetes clinic uses a template created on the practice software of the routine clinical measurements reviewed during each patient visit. Reviews every three months are recommended, with the review consultations anticipated to be provided mostly by the practice nurse in a patient with stable risk factors. Some 70% of the cohort attended the clinic between one and five times. This provides an opportunity for reduction in GP consultations, unless complications or concerns arise, at which time the patient is reviewed by the GP during the same visit.

Annual reviews should involve complete cardiovascular, neurological, ophthalmology and renal assessment, as well as non-routine assessments by the consultant or senior registrar on a one to two year basis.

Improved quality of care

The initial audit identified the shortcomings of the practice in its unstructured approach towards managing its population with diabetes. The subsequent development of a nurse-led clinic has produced results that demonstrated the impact on the delivery of quality care for the practice diabetes population through a structured framework.

The nurse-led clinic in Rialto Medical Centre has produced results that show improved clinical measurements in HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, renal function and total cholesterol (see Figure 1). Some of the improved results can be attributed to increased focus on documentation of clinical parameters, highlighting the benefits of such a structured approach.

Structured care is generally accepted as providing more successful healthcare delivery for this population8,9 and as being cost-effective.10 These clinics run by clinical nurse specialists offer focused examination and investigations, with systematic recording and documentation of results and referrals. This provides an accurate, up-to-date measurement of the state of each patient’s chronic condition and the opportunity to identify trends with regard to their clinical measurements.

At the time of publication, Rialto Medical Centre has 120 type 2 diabetes patients, of whom 90 are enrolled in the practice diabetes clinic. Those newly diagnosed are now immediately referred to the practice clinic and only referred to secondary level care for one to two yearly reviews, or if their condition is poorly controlled warranting specialist intervention.

Structured care

Nurse-led clinics provide structured care that is measurable and easily audited. These clinics benefit the patients, the practice and secondary level care with improved health outcomes, reduced consultations and reduced cost to the health service. These clinics offer an invaluable opportunity to provide improved quality care in the management of chronic conditions in primary care.

Authors: Conor O’Kelly is an intern at St James’s Hospital; Anna Foy and Aimee Murphy are second year GP trainees on the TCD/HSE GP training programme; Jennifer Clarke is a clinical nurse specialist in diabetes and Siobhan O’Kelly, GP at Rialto Medical Centre, Dublin.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)