CHILD HEALTH

DIABETES

Promoting physical activity for children: Opportunities and challenges

Healthcare professionals interacting with children, young people and their families have an important role to play in promoting physical activity to patients

May 21, 2019

-

Similar to a school report, countries globally have been grading their national physical activity data against a standard set of grades from A to F.1 Children across the globe have been graded with a ‘D’ for the amount of physical activity they do,1 and the island of Ireland also achieved a D, meaning we could do much better.2 This article considers what healthcare professionals can do to promote physical activity with their patients and service users.

Physical activity in children has many physiological and psychosocial benefits.3 In Ireland, the guidelines for children aged two to 18 are that they should achieve at least 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) each day while also including muscle-strengthening, flexibility and bone-strengthening exercises three times a week.4 Incidentally, guidelines for adults in Ireland are to do at least 30 minutes of moderate activity five days per week (or 150 minutes a week).

Any discussion on physical activity benefits from a distinction between terms that are used interchangeably.5 Physical activity is “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.” Under this umbrella we have activities such as playing, walking for transport, household chores and recreational activities.

Exercise is a subcategory of physical activity that is categorised as planned, structured, repetitive and purposeful.

Fitness is having the health, the skill or the ability to perform daily tasks and activities to a particular level. Cardiovascular fitness specifically is that which is developed through doing activities at an MVPA intensity.

Inactivity is defined as not meeting the aforementioned physical activity guidelines. Being sedentary is sitting too much across the day.6

In adults, there has been a call to promote physical activity, reduce sedentary behaviour and build cardiorespiratory fitness via targeted public health efforts.7 In children, it may also be prudent to look at all three factors for meaningful, long-term prevention of ill-health.

Inactivity is too complex for it just to be tackled at an individual level. A systems-based approach means “policy actions aimed at improving the social, cultural, economic and environmental factors that support physical activity, combined with individually focused (educational and informational) approaches”.8,9 Healthcare professionals have a key role in the provision of education and information to individual members of society. Being a voice in the community to advocate for physical activity will benefit current and future generations.

Healthcare professionals interacting with children, young people and their families have an important role to play in promoting physical activity to patients. A number of key barriers to this have been identified10:

Time

With short patient contact time, simply querying the amount of physical activity someone does is a great start. A question like “over the past seven days on how many days were you physically active for a total of 60 minutes per day?” followed up with “try to be active for at least 60 minutes every day. When I see you for your next appointment we can chat again about this and see how an activity plan might work” is a time-friendly approach.

Knowledge

The basics of knowing the physical activity guidelines is a great start. That “exercise as a medicine… works in a variety of disease conditions and is extremely successful in preventing many diseases”,10 and also that physical activity encompasses so much more than structured exercise is critical knowledge for any healthcare professional to have.

Skills

Brief interactions with adults in primary care has shown success.11 This could include sign-posting to local physical activity offerings (anything from gyms to parks and outdoor spaces) or delivering advice on ways to meet physical activity guidelines. Even helping a family set a physical activity goal using SMART goals (ones that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-based) could be useful.

Chance for success

An individual healthcare professional may struggle to see their ability to change a patient’s behaviour. This is a common concern. Comments about the global inactivity problem from MSc-level students (typically clinicians and nurses from all corners of the globe) illustrate this:

“The world has no chance of reducing obesity and inactivity levels.”

“Prevention using lifestyle (physical activity and dietary changes) is too difficult for people to actually do, that is what got them into the situation in the first place!”

“People don’t think they need prevention efforts even when they have been told they are at risk.”

“Large scale environmental and policy changes are needed, tackling the individual is meaningless and neither cost- nor time-effective.”

Remember, healthcare professionals are part of the system-based approach to tackling this issue. Chances of success are greater when many sectors work together strategically. The recently launched World Health Organization Global Action Plan on Physical Activity9 describes actions to effect a change in all parts of the ‘system’. This includes an action (Active People action 3.2) that the professional societies that represent healthcare professionals should “support the development and dissemination of resources and best practice guidance on the promotion of physical activity through primary and secondary healthcare and social services, adapted to different contexts and cultures.”

Ireland’s Physical Activity Plan12 also includes an action (action 23) for the Irish health services and the Department of Health to “develop and implement a brief intervention model for delivery of physical activity advice.”

This could be useful if other parts of the system are also playing their part: combining healthcare professionals’ physical activity advice with, for example, a national social media campaign, some high-impact mass participation events, education in schools, and regular local activities. All this might be enough to trigger a family into action.

Using screens

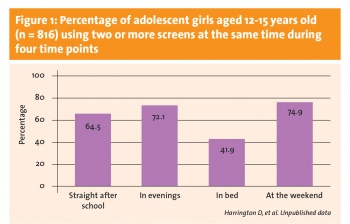

A common refrain from parents when asked about their child’s physical activity is “I can never get them off their screens”.13 The challenge is real. An Irish study found that a group of adolescent girls spent over 18 hours each day sitting or lying down.14 In a sample of adolescent girls in the UK, it was found that the majority use two or more screens at the same time (‘screen stacking’) across the day (see Figure 1).

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)