DERMATOLOGY

CANCER

Recognising types of skin lesions and when to refer

The most important decision to make when finding a lesion is to decide whether it is suspicious and warrants further investigation

February 7, 2014

February 7, 2014

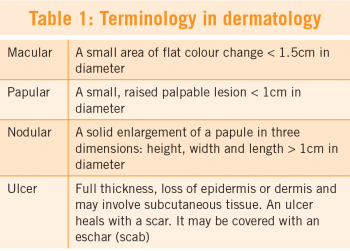

A lesion is any single area of altered skin. It may be solitary or multiple. Lesions may be macular (flat), papular (raised), or nodular (solid) (see Table 1). Lesions can be further subdivided according to their configuration, such as their shape or outline. Some lesions can be discoid (coin shaped), linear (in a line), or annular (lesions grouped in circle). Lesions can also be categorised according to their colour: pigmented (brown,black or blue) or non-pigmented (skin coloured, red, purple or white).

With careful examination, using good light and magnification when necessary, most lesions can be easily recognised and diagnosed clinically. Overlying crust or scale should be removed carefully with a scalpel blade to reveal the true nature of a lesion. Otherwise it is like trying to examine a patient’s chest using a stethoscope with their clothes on. A good dermatology atlas or website with lots of photos is very useful when trying to identify lesions.(eg. www.dermnetnz.org or www.dermis.net or www.dermatlas.net)

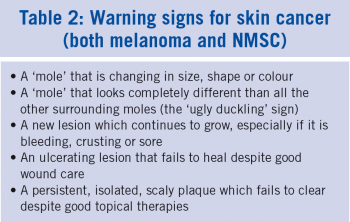

The most important decision to make when examining a lesion is to decide whether it is benign or malignant. Even more important is not to miss a melanoma which, unlike most other forms of skin cancer, can grow rapidly, spread beyond the skin quickly and can be life-threatening, even in young adults. A recent study in my own practice showed that almost a quarter of the invasive melanomas seen had little or no pigment (amelanotic or hypomelanotic) (see Picture 1).1 Melanomas can mimic lots of tumours, and so all skin lesions should be examined carefully to rule out a melanoma, whether they are pigmented or not (see Table 2).

The recently launched National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) guidelines on melanoma encourage GPs to refer all lesions suspicious of melanoma to a pigmented lesion clinic, which are usually located in tertiary referral hospitals.2 However, the standard of lesion recognition among GPs in Ireland is very varied. Some GPs have high levels of skills and experience including dermoscopy training, while others have little or no training in lesion recognition. There is already evidence that pigmented lesion clinics are being overrun with mostly harmless benign lesions, leading to excessively long waiting times for those who turn out to have a melanoma.3,4

Pigmented lesion clinics may also fail to pick up non-pigmented melanomas. In a recent audit of the melanomas in my own practice, amelanotic melanomas were biopsied as quickly as pigmented melanomas (average of nine days v eight days).1 Studies have shown that the outcome is not affected by who carries out the initial excision of a suspicious lesion or where the initial diagnostic excision is carried out (eg. by a GP with experience in skin surgery, versus a dermatologist or a plastic surgeon).5,6,7,8,9,10,11

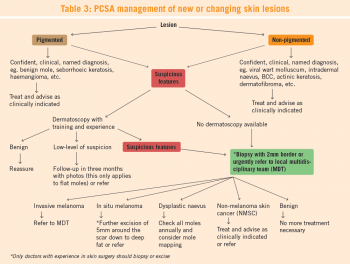

The Primary Care Surgical Association recently launched an algorithm for assessing skin lesions with a view to ruling out melanomas (see Table 3).12 Any lesion where a confident clinically named diagnosis cannot be made should be viewed with suspicion and the patient should be referred to a colleague with more experience, or the lesion should be biopsied at the earliest opportunity. When biopsying a lesion suspicious of a melanoma, the complete lesion should be removed with a 2mm border of clear skin all round and including the upper subcutis. The specimen should be sent to a histopathologist with experience in examining skin lesions and melanomas. The Primary Care Surgical Association recommends that only doctors with experience in skin surgery and skin cancer should carry out this type of work. GPs should not treat invasive melanomas. If an invasive melanoma is found then the patient should be referred immediately and urgently to the regional melanoma multidisciplinary team (MDT) for further staging and treatment.

According to the PCSA guidelines, if a suspicious pigmented lesion is seen by a GP who does not have experience in skin cancer and skin surgery, then the patient should be referred urgently to a GP colleague who has these skills or else to a pigmented lesion clinic or a plastic surgeon, which are located in regional or university hospitals throughout Ireland. Referral to the pigmented lesion clinics should be via the NCCP cancer referral template. The choice of whether to refer to a GP surgeon or to the regional pigmented lesion clinic will be dictated by how quickly an appointment can be made for the patient; how quickly a diagnostic excisional biopsy can be carried out if required; the level of suspicion of a melanoma; and the preference of the patient. Studies have shown that biopsy of suspicious skin lesions in primary care by GPs with experience in skin cancer and skin surgery can lead to more rapid diagnosis and a quicker pathway to definitive treatment of the patient found to have melanoma, with lower costs and more convenience to the patient, especially those who live outside major urban areas. 1

Dermoscopy helps greatly in making an accurate clinical diagnosis of both benign and malignant lesions, especially pigmented lesions (see Picture 2). In Australia, a dermoscope is as common as a stethoscope in general practice. Dermoscopic images are easy to take with a digital camera attached to the dermoscope and are very useful when following up flat pigmented lesions where the diagnosis of melanoma is unlikely. The clinical and dermoscopy features can be followed up after three months, looking for a change in the lesion. Clinical and dermoscopy images are also useful when referring a patient, as they can alert the doctor receiving the referral about the nature of the lesion and the possibility of whether it could be a melanoma or not. However, nodular lesions that have even a low suspicion of melanoma should be excised or referred urgently, as nodular melanoma can grow rapidly and spread beyond the skin early and are therefore not suitable for follow-up observations.

There is a steep learning curve in the use and interpretation of lesions using dermoscopy and even basic dermoscopy would require at least a one-day training course by an expert dermoscopist. Ongoing training in more intermediate and advanced dermoscopy is also advisable. The University of Wales College of Medicine runs a distance learning course on dermoscopy over 12 weeks, which is easily accessible to most doctors in Ireland, as most of the teaching is done online.13 The Primary Care Surgical Association (www.pcsa.ie) and the Primary Care Dermatology Association of Ireland (www.pcdsi.com) also run beginners and advance dermoscopy courses.

When examining an individual lesion the doctor should pay particular attention to the size, colour, shape and volume and also assess whether the lesion is tender or not. As well as examining the individual lesion with good light and magnification, any adjacent lesions and all other parts of the body should be assessed as clues may be found on other parts of the body that may help clinch the diagnosis. For example, if there is a pigmented, slightly scaly, waxy, stuck-on lesion on the patient’s forehead and the patient has multiple seborrhoeic keratosis on their back, then the most likely diagnosis would be a seborrhoeic keratosis on the forehead.

Solitary lesions, particularly if they are new, growing, crusting, bleeding or tender to touch should always be viewed with suspicion, as these lesions are more likely to be malignant. On the other hand, multiple lesions that all look similar are usually benign, such as stable moles, warts, molluscum contagiosum or seborrhoeic keratosis.

It is important to realise that there is a lot of crossover between pigmented and non-pigmented lesions. Lesions that are normally non-pigmented may present as a pigmented lesion such as a pigmented BCC, and lesions that are normally pigmented such as a melanoma, may present as a non-pigmented lesion. Other lesions such as intradermal nevi may be pigmented or non-pigmented, even in the same patient.

Skin lesions do not always present as the classical text book description. In fact, it can often be impossible to differentiate a BCC from an SCC or an actinic keratosis from an area of Bowen’s disease or an early SCC on clinical grounds alone. Some tumours may have mixed pathology (eg. basosquamous carcinoma) and occasionally two tumours may grow beside each other (collision tumours). In primary care, the most important thing is to decide whether the lesion is suspicious and warrants further investigation such as biopsy or referral. The exact diagnosis will be made by the pathologist.

The Primary Care Surgical Association will be having sessions on lesion recognition at its annual scientific meeting in Cork on April 11-12. Further details can be found on the website www.pcsa.ie

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)