CANCER

Sarcoma review: Types, diagnosis and treatment options

The term ‘sarcoma’ is credited to an English surgeon, John Abernethy, who sought to create the first tumour classification system in 1804

May 1, 2018

-

Sarcomas are malignant tumours of mesenchymal origin that can be broadly divided into bone and soft tissue tumours. There are over 100 histological subtypes that are usually named according to the tissue they most closely resemble.2 Symptoms are not always apparent and can vary according to the location of the tumour; often, they present as a mass that is slowly enlarging and usually painless, unless there is nerve involvement or impingement. Sarcoma can take on the characteristics of common cancers as well as benign tumours, and can also be mistaken for other less serious health conditions. Most tumours arise de novo, however some risk factors have been identified, for example prior irradiation, chronic inflammation, Paget’s disease, retinoblastoma and Li Fraumeni syndrome.

How common is sarcoma?

Sarcomas make up less than 1% of adult tumours and 12% of those in children.3 There are approximately 60 new cases per year in Ireland. The majority, about 80%, will be of soft tissue origin. For the purposes of this article only the most common types of sarcomas will be covered. Of the soft tissue tumours, these include liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Bone tumours covered will include osteogenic sarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma and chondrosarcoma.

Types of sarcoma

Soft tissue sarcomas

Liposarcoma arises from adipocytes and usually occurs in the extremities and the retroperitoneum. Patients are typically 40-60 years of age and the lung is the most frequent site for metastases. Leiomyosarcoma is derived from smooth muscle cells, common sites include the retroperitoneum and the uterus. It is slightly more common in women.

Synovial sarcoma arises near joints and tendon sheaths and is found in the extremities of young adults. Histologically it bears resemblance to synovial cells, however the cell of origin is unknown. It is one of the few forms of sarcomas that metastasise to lymph nodes. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common subtype found in children and adolescents and also metastasises to lymph nodes. Common sites include the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, parameningeal areas, extremities, retroperitoneum and the orbit.

Bone sarcomas

Osteogenic sarcoma is the most common sarcoma of the bone and the second most common primary bone tumour following multiple myeloma. It is characterised by an increase in the production of osteoid by malignant osteoid-producing osteoblasts. There are 15-20 new cases of osteogenic sarcoma per year in Ireland and it is more common in males under the age of 20 years. It can also present in elderly patients with exposure-related risk factors, as discussed above.

Ewing’s sarcoma is predominantly found in patients under the age of 20 years. It is a round cell tumour, however its exact cell of origin is unknown. It mostly occurs in long bones and metastasises to the lungs. Finally, chondrosarcoma is a tumour that produces a cartilaginous matrix with poor vascularity. Most are slow-growing and slow to metastasise. Chondrosarcomas can be divided into primary and secondary tumours.

Presentation

Most soft tissue sarcomas present as a mass that is enlarging and usually painless, unless there is nerve involvement or impingement. The following factors should prompt further investigation and urgent specialist surgical referral:4

- Large lesions measuring 5cm or more

- Lesions that lie deep to the fascia

- Lesions that are increasing in size or painful

- Lesions that have recurred after previous excision.

Primary bone tumours can present incidentally on imaging, with a painless or painful hard mass, pathological fracture, or symptoms of metastases.

Diagnosis

All patients should have a thorough history and examination with a blood panel to include a full blood count, renal and liver function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, and parathyroid hormone. Ideally patients should have these bloods sent prior to referral. All patients will require imaging, starting with a plain radiograph of the area. This should include two views and visualise the entire bone plus the joint above and below to rule out skip lesions.

Computed tomography (CT) is useful for evaluation of cortical involvement and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for soft tissue lesions. Patients should have their staging completed with a CT thorax to rule out pulmonary metastases plus a bone scan or CT-positron emission tomography (PET) if multiple lesions are suspected.

Biopsies

If there is the potential for lymph node metastases then a sentinel lymph node biopsy may be carried out. In most cases, patients should have a biopsy of the lesion sent and all should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team setting.

One of the most important learning points is the importance of biopsy planning in these patients. The consequences of a poorly carried out procedure can be devastating. One study reported that 4% of patients referred to specialist centres required amputation directly as a result of a poorly performed biopsy.5 There is also an increase in the risk of metastases in those who have had inadequate resection before referral to a tertiary centre.6

Biopsies should ideally be carried out by the treating surgeon, or at least after direct communication from them. Open biopsies should be linear, along the line of incision for definitive surgical resection so that the biopsy tract can be included in the specimen. The incision should cross as few fascial planes as possible while avoiding exposure of neurovascular structures. Exposed structures are considered contaminated and should be excised, which can compromise limb-preserving surgery.

Meticulous haemostasis should also be maintained and the biopsy should be sent for frozen section, to ensure correct sampling, plus culture and sensitivity. Two staging systems are commonly used for sarcomas: Enneking7 and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) systems.8

Treatment options

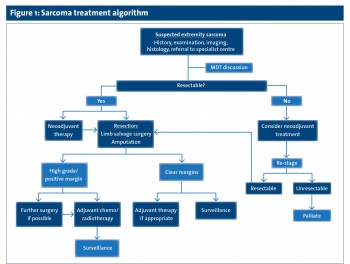

All suspected sarcomas should be promptly referred to a specialist centre where sarcomas are dealt with frequently (see Figure 1).

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)