CANCER

Soft tissue sarcomas in Ireland: A review

A review of soft tissue sarcomas in Ireland

May 16, 2016

-

Soft Tissue Sarcomas (STS) are a rare heterogeneous group of mesenchymal neoplasms that can arise from virtually any anatomic site. They represent less than 1% of malignant tumours in adults and 7% of paediatric malignancies.1 As these are relatively rare tumours, there is a gap in knowledge with regards to their aetiology, molecular genotyping and risk factors. Commonly reported risk factors include exposure to ionising radiation, especially during cancer treatments.

An association with certain inherited syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome (p53 mutation), Gardner syndrome (APC mutation) and von Recklinghausen disease (neurofibromatosis type 1: NF1 mutation) has been reported.2 Furthermore, there is a lack of standardised classification for this rare tumour group. STS are broadly grouped into 18 categories even though there are dozens of histological types. A report by the RARECARE group in Europe showed that sarcomas make up a significant number of cases in absolute terms and form one of the major families of cancers in the rare cancer group.3

Incidence of STS

An average of 176 STS cases are diagnosed in Ireland every year.4 The age-adjusted incidence rate, as per a recent epidemiological report on STS in Ireland, is 4.48 per 100,000 person-years.4 This is at the higher end of the spectrum of published international incidence of STS: between 1.8 and 5.0 per 100,000 person-years. The incidence of STS in Ireland is comparable to the UK (4.25 per 100,000 person years) but lower than that in the US (5.03 per 100,000 person-years) and Northern, Central and Southern European regions (4.5-4.7 per 100,000 person-years). It is higher than Easter European countries (3.3 per 100,000 person-years)5 and certain individual European countries including Sweden (1.8 per 100,000 person-years), Austria (2.4 per 100, 000 person-years), Denmark (3.2 per 100,000 person-years), and Switzerland (3.6 per 100,000 person years).6

There is considerable variation in the grouping of STS among different reporting authorities around the world. The coding practices have also changed significantly over time as classification of the tumours has evolved. This is one of the explanations for the wide variation in incidence figures of STS around the world. The other contributing factors include different population characteristics, geographical factors and influence of risk factors in different regions of the world.

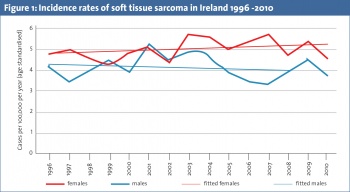

The incidence of STS has fluctuated considerably with an overall gradual rise over the last two decades (see Figure 1). The incidence over last few years has been similar to that in the mid 1990s.4 This is similar to the rising incidence of sarcomas worldwide and is most probably due to better recognition and diagnosis as well as the influence of risk factors, eg. increasing radiation treatments and increasing cases of Kaposi sarcoma which is often associated with AIDS.7 Again, the change in coding practices over time should be borne in mind while interpreting these figures.

Epidemiologic variations

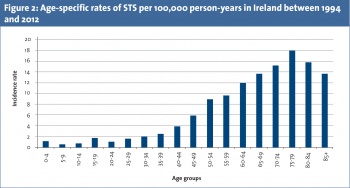

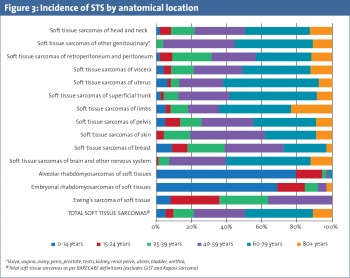

STS occur more frequently diagnosed in older individuals with the highest reported incidence in people between 75 to 79 years in Ireland (see Figure 2). Certain types of STS have a propensity to occur in children and young adults, such as rhabdomyosarcomas (< 15 years of age) and Ewing’s sarcoma (15-25 years of age) (see Figure 3). Females have a slightly higher age adjusted incidence rate for STS in Ireland with a male to female ratio of 0.83:1 (see Figure 1).

Certain types of STS (excluding male specific STS) such as Ewing sarcoma, alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas, head and neck, skin (and Kaposi) sarcomas are more common in males.8 The gender distribution of STS is variable across different geographical distributions in the world. Higher incidence of STS in uterus and breast in females as compared to paratesticular STS in males could be one of the explanations for female preponderance of STS in Ireland (Figure 1).

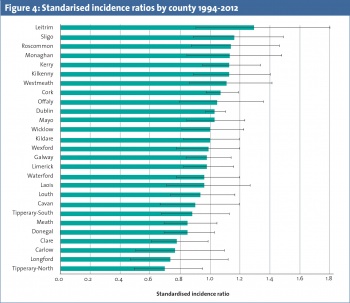

Geographically, the incidence of STS in Ireland varies across different counties but this is not significant statistically (see Figure 4). The age adjusted incidence rates are highest in county Leitrim and lowest in Longford in Ireland.4 There is no definite explanation for the current variation in incidence across geographical regions in Ireland. The interpretation of these differences must be done with caution due to relatively small absolute numbers of STS in each county.

Tumour sites

STS can arise from virtually any anatomical site but most frequently they arise in the limbs with approximately two-thirds of these arising in the legs and buttocks. The other common sites include uterus (16%) and skin (10%).4 As a proportion of invasive cancers, 85% of all soft tissue tumours arising from limbs and 75% of all cardiac tumours are sarcomas.8 They are not as frequent in other anatomical sites, representing less than 0.5% of all cancers in breast, skin and other visceral sites.

Presentation

Clinical presentation of STS can be difficult to define considering the heterogeneous sites of origin. Urgent referral should be sought for a patient who presents with a soft tissue lump with any one of the following features:

• Increasing size

• Size > 5cm

• Deep to the deep fascia

• Painful.9

Over 90% of STS in Ireland are diagnosed symptomatically. Approximately 12% of heart sarcomas are diagnosed either incidentally or at autopsy in Ireland.8

STS management

Management options for STS include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Surgical excision of tumour is standard treatment for all patients with adult-type localised STS. Postoperative radiotherapy is considered as the standard approach for almost all intermediate or high grade STS. The role of chemotherapy in management of STS remains controversial and it may be considered for individual patients with potentially chemosensitive tumour subtypes but there is no proven benefit.9 Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for STS in Ireland with over 78% of tumours diagnosed between 2007 and 2012 undergoing surgical excision.

Adjuvant treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy were utilised in 38% and 25% of STS patients. STS in the limbs, superficial trunk, breast uterus, paratestis, genitourinary system and skin are commonly managed by surgical excision, while STS in the heart, paraorbit and mediastinum are less frequently amenable to tumour directed surgery.

Chemotherapy is more frequently utilised in management of certain STS such as rhabdomyosarcomas and Ewing’s sarcomas. Radiotherapy is more often utilised in the treatment of STS in mediastinum, limbs, pelvis and paraorbit. Just over one in ten (11%) STS patients in Ireland do not undergo any tumour directed therapy, and half of patients with heart sarcomas receive no therapy.8

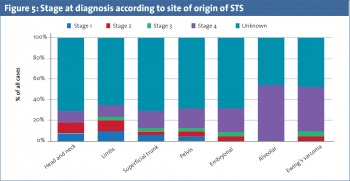

Tumour staging is performed in only 14% of STS cases diagnosed in Ireland with the largest proportion of tumours staged at diagnosis belonging to the stage IV group (see Figure 5). STS in limbs have a tendency to be diagnosed earlier than others.

Survival

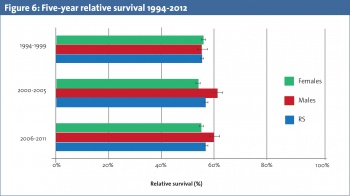

Survival rates of STS in Ireland (see Figure 6) are slightly lower than the European average but comparable to those in the UK (56%) and Eastern Europe. The overall five-year relative survival rates of soft tissue sarcomas increased between 1994-1999 and 2001-2005 from 55.1% to 57.1% in Ireland. This is statistically similar when compared to five-year relative survival rates in the UK (54% in 1995-2000 and 56% in 2001-2005).10 These observations are subject to differences in coding between UK and Ireland.

The overall five-year survival of STS in Ireland over the last two decades was 56%.5 This is 5% less than the US (65%; 1975-2011) and southern Europe (61%), which have among the highest reported survival rates for STS. Survival rates are lower in certain subtypes, such as Ewing’s sarcoma of soft tissue and uterine sarcoma, compared to the European figures. STS of pelvis, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma and superficial trunk have a better relative survival in Ireland compared to the European average.

The survival rates for STS in Ireland are higher in men (59%) compared to women (55%), which could be explained by the relatively poorer survival rates for female-specific STS, such as uterine tumours, compared to a near 100% survival in well differentiated liposarcomas occurring more frequently in males. The survival rates of STS have deteriorated over time in females compared to males in whom survival has improved over time (Figure 1). This phenomenon has not been observed in other countries around the world.

The relative survival varies considerably according to the anatomical site: STS of the skin having the highest survival of 91% followed by breast (phyllodes, 81%) and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs; 78%). The poorest survival rates are seen in female genitourinary STS (23%) and uterine sarcomas (43%). Ewing’s sarcomas of soft tissue and peritoneal STS also have poor survival rates compared to other STS.8

Irish Sarcoma Group

A plausible explanation for poorer survival rates of STS in Ireland could be the lack of centralised sarcoma management and specialised centres considering it is management of sarcomas requires multidisciplinary expertise and knowledge.4 The recent establishment of the Irish Sarcoma Group is a preliminary step in this direction.

This is an association of specialist clinicians, nurses and allied professionals who are involved in the care of sarcoma patients in Ireland. The group’s aim is to develop and strengthen the national sarcoma services and raise awareness about this rare neoplasm among the public and medical professional. It also aims to provide education and training in best practice of sarcoma management and to promote research for the development of more effective treatment and care of sarcomas in Ireland. Increasing awareness, better recording and staging of STS, and multidisciplinary specialised centres for management of STS may improve survival rates of STS in this country.

Conclusion

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare heterogeneous tumours. Their incidence is on the rise around the world and is showing a similar trend in Ireland. The survival of patients with STS in Ireland is lower compared to the European and the US average, but is comparable to the UK. Recent centralisation of sarcoma services in Ireland with the establishment of the Irish Sarcoma Group may have a positive impact on the survival.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)