WOMEN’S HEALTH

Update on contraception

Many factors come into play when choosing contraception and doctors need to take a good history and discuss all suitable options so each woman can make an informed choice

September 1, 2013

-

The average age for first sexual intercourse in women in Ireland is 18 years and the average age of menopause is 51. This means that women may need contraception for more than 30 years of their life.1 Women want a contraceptive that is safe, reliable and easy to use, suits their lifestyle and is affordable. GPs need to be able to offer a wide range of choices to women, be able to discuss the risks and benefits of each method, and deal with problems as they arise. This article looks at the issues relating to prescribing contraception and offers useful sources of information for further reading.

When prescribing contraception, a helpful guide is the UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraception Use (MEC).2 This document, available at www.fsrh.org, reviews the criteria for use of contraception, offering guidance on the safety of use of different methods for women with known medical conditions (for example, migraine, diabetes) or with specific characteristics (for example, high BP or high BMI, smoker). The website of the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) in the UK (www.fsrh.org) provides excellent guidance documents for health professionals on all aspects of contraception.

Key considerations

Discuss sexually transmitted infections

Nearly 60% of STI notifications in 2011 related to young people under the age of 30. Young people attending for contraception should be informed about STIs and routes of transmission, and about correct and consistent use of condoms. They should be encouraged to have regular STI testing, particularly when they have been with a new sexual partner. The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV has produced a useful guideline for testing for STIs in general practice (www.bashh.org).3

Ask about enzyme inducing drugs

It is important to ask about enzyme inducing drugs (EIDs) at a contraception consultation. Enzyme inducing drugs affect the efficacy of the combined oral contraceptive (COC), as well as the efficacy of progesterone only pill (POP), progesterone implant and levonorgestrel emergency contraception. However, EIDs do not appear to affect the efficacy of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) (Depo-Provera), the intrauterine system (Mirena) or intrauterine device (IUD). A recent guidance document by the FSRH, Drug interactions with hormonal contraception, contains a full list of enzyme inducing drugs, which includes St John’s Wort, the antibiotics rifampicin and rifabutin, several antiepileptic medications and antiretroviral drugs.4

Patient information leaflets

The use of patient information leaflets may help a woman to make an informed decision. Information leaflets can be downloaded from the following websites:

www.thinkcontraception.ie, www.fpa.org.uk, www.brook.org.ukChoosing a contraceptive method

Combined hormonal contraception (COC)

The COC is the commonest form of contraception used by Irish women, with one in four women choosing this method. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the most significant risk associated with the COC. In the general population, the baseline risk of VTE is five cases per 100,000 women each year. The risk increases to 15 in 100,000 for women on a COC containing levonorgestrel and to 25 in 100,000 for those containing desogestrel and gestodene. A pill containing drospirenone appears to have a risk of VTE somewhere between that for levonorgestrel-containing pills and those containing desogestrel or gestodene, but more studies are needed to confirm this.5-6 For a woman starting on the COC for the first time, a monophasic COC containing levonorgestrel is a good first choice.

Before prescribing the COC for the first time, blood pressure and BMI should be recorded. A BMI of 35 is considered a UK MEC-3, meaning that the risks usually outweigh the benefits.2 Migraine with aura is a medical condition for which the COC presents an unacceptable risk (UK MEC-4).2 It is recognised as good practice that an annual visit to check BP and BMI is sufficient for women on the COC.7

The issue of weight gain arises frequently when prescribing the COC. Women can be reassured that there is no evidence of a causal relationship between the pill and weight gain, according to a Cochrane review.8

The COC can also be prescribed as a treatment for acne. It acts by suppressing leutinising hormone (LH). A recent Cochrane review found that all pills studied seemed to have a similar effect on acne and there was limited data to say that COC containing cyproterone acetate (Dianette) was superior to levonorgestrel containing pills.9 Dianette is associated with a 1.5-2 fold increase risk of VTE compared to a levonorgestrel-containing pill.5-6 The COC containing cyproterone acetate (Dianette) is licensed for the treatment of severe acne vulgaris but women should be switched to another pill once the acne settles.10

There are new recommendations on the use of antibiotics with the COC. The WHO and the UK Medical Eligibility Criteria state that it is not necessary to advise women to use extra precautions when they take antibiotics while on the COC.3 Antibiotics that are enzyme inducers such as rifampicin and rifabutin are an exception to this, as explained above.3

Missed pill advice has also changed in recent years. The traditional teaching was to advise women to use extra precautions or avoid unprotected sexual intercourse for seven days following one missed COC pill. Recent guidance states that woman can miss one pill without having to use extra precautions.11 This new guidance states that women must take extra precautions following two or more missed pills. At what point in the packet the pills are missed will dictate whether the postcoital contraception should be taken or not. Despite this new guidance, many doctors think it is simpler to stick to the old rule and advise women not to miss one pill. Women should always be informed that the critical time for missing a pill is at the beginning or end of a packet.

The contraceptive patch containing ethinyl estradiol (EE) and norelgestromin might suit women who tend to forget to take pills. The patch is applied weekly for three weeks, followed by a patch-free week. One study suggested that patch users may experience more adverse effects. Another device that women might choose is the contraceptive ring containing EE and etonogestrel. It is inserted into the vagina for three weeks, followed by a ring-free week. Both the ring and the patch have the same MEC and failure rates as the COC. Both these options may be useful for women who regularly travel across time zones or women with bowel absorption problems or bulimia.

Progesterone only pill (POP)

The POP is a good alternative for women with contraindications to the COC. The pill containing norethisterone (Noriday) works by altering cervical mucus and blocking sperm passage and is generally only suitable for women over 35 year of age. The newer POP, Cerazette, which contains desogestrel, works by preventing ovulation in 97% of cycles and thus appears to be more effective than Noriday, and it can be prescribed to younger women.12 It can be taken up to 12 hours late. The prevalence of bleeding problems appears to be similar with both pills and this is a major drawback of prescribing these pills to young women.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC)

When a young person requests contraception, she should be offered a wide range of options to consider, including the LARC methods.13 All the LARC methods have lower failure rates than barrier methods and hormonal pills, and have been shown to be more cost effective than the pill even at one year of use.13 The LARC methods do not contain oestrogen and so they are useful for women with contraindications to taking oestrogen. The recent Choice study concluded that the effectiveness of LARC is superior to that of contraceptive pills, patch or ring and is not altered in adolescents and young women.14

Depot medroxy progesterone acetate (DMPA)

Studies have shown that for women of reproductive age, DMPA (Depo-Provera)may reduce bone mineral density (BMD). However, there is no evidence that the reduction in bone density is related to increased fracture risk and it has been shown that full recovery of bone density occurs by one year after stopping. It is important to take a detailed history to assess osteoporosis risk factors such as family history, smoking status and medications in women considering this method. Women using this method should have a detailed review every two years to assess for any risk factors for osteoporosis and to fully inform them of the risks.15

There has been particular concern about the use of DMPA in women aged under 18 years who may not have attained their peak bone mass. The FSRH indicates that DMPA can be used in women under the age of 18 years after consideration of other methods.16 Some experts recommend that DMPA be used as a bridging method for 12-18 months in this age group. Young people should be informed that using this contraceptive can be associated with a small loss in bone mineral density that is usually recovered after discontinuation.16 Women should also be informed that DMPA has been causally associated with weight gain and that after stopping this method there is a delay in return to fertility of up to 12 months.

Progesterone subdermal implant

The progesterone subdermal implant (Implanon NXT) is a single rod which is inserted subdermally in a woman’s upper arm. Etonogestrel is released from Implanon NXT in a controlled fashion over three years. It primarily acts by inhibiting ovulation but in the third year the effect on the cervical barrier is an important secondary effect. It is an extremely effective contraceptive and the pregnancy rate is fewer than one in 1,000 over three years.13

It is important to warn women about the possibility of bleeding problems post-insertion so that they do not have unrealistic expectations. Post-insertion bleeding patterns have been summarised in the NICE guidelines as follows: At one year post-insertion, 20% of women are amenorrhoeic and 50% of women have infrequent, frequent or prolonged bleeding which may not settle with time.13 For those who have troublesome bleeding, there are various possible treatment options that have been studied, such as prescribing the COC or mefenamic acid for three months.17

The subdermal implant can be inserted any time in the cycle once you are reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant. In practice this means that if a women is taking an anovulant form of contraception such as the COC, POP (Cerazette) or DMPA, then the implant can be inserted at any time.18

Intrauterine devices and young women

The use of intrauterine device (IUD) and intrauterine system (IUS) is uncommon in Irish women and is rarely offered to young women. At least part of the reason may be the persistent myths surrounding its risks. It is important that healthcare professionals provide accurate information that will help dispel these myths.

It was widely thought that IUDs caused pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), tubal infertility and ectopic pregnancy; however, evidence suggests that these assumptions are all false.19 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is actually lower in women with an intrauterine device than in those using no contraception, indicating a protective effect.20

Available evidence suggests that the risk of PID contracted through sexually transmitted infection (STI) is not greater in women with intrauterine contraception. The risk of PID with IUD use is low and relates to the insertion process and background risk of STIs.21 It is considered good practice to assess STI risk by taking a sexual history and to screen for chlamydia prior to insertion if indicated. Since the test for chlamydia is a simple first pass urine or endocervical swab, some doctors have a policy of screening all women prior to insertion of IUD/IUS.

It is often incorrectly thought that an IUD/IUS is only suitable for women who have had children. However, an IUD/IUS can be appropriate for nulliparous women who are at low risk of STIs; for example, if in a stable relationship. There is evidence to show that the use of IUDs for nulligravid women with low risk of PID is as safe and reliable as among parous women.22-24

IUD/IUS expulsion, bleeding and pain are slightly more likely among nulliparous women than among women who have had children.23-26 Correct insertion, with the IUD/IUD placed up to the fundus, is thought to reduce the likelihood of expulsion.22

An Lng-IUS can be a useful option in young nulliparous women in whom oestrogen is contraindicated or who have heavy, painful periods or painful endometriosis. Pre-insertion counselling must include a discussion about the mode of action, risk of perforation, expulsion and lost threads, as well as bleeding problems and hormonal side effects.

The primary mode of action of the Lng-IUS is endometrial atrophy, preventing implantation. Secondary effects include a cervical mucus effect and ovulation suppression. The Lng-IUS has a pregnancy rate of fewer than five in 1,000 over five years so it is a very reliable contraceptive.13 Irregular, light or heavy bleeding is common in the first six months following insertion of the Lng-IUS. Continuation rates may be improved if women are counselled in advance to expect these side effects. Approximately, 65% of women are amenorrhoeic or have light bleeding at one year following insertion.

Copper IUDs are rarely offered to women in Ireland despite the fact that this can be a really good option for women who want a completely hormone-free method. The copper-IUD primarily acts by its toxic effect on ovum and sperm, preventing fertilisation. It also has an effect on the endometrium that prevents implantation and an effect on cervical mucus that affects sperm penetration. The pregnancy rate is fewer than 20 in 1,000 over five years.13 Spotting, heavier or longer periods are common in the first three to six months following insertion, so this method should ideally be considered in women who have light periods and who want a hormone free method.

Contraception for women over 40

As age increases, women are more likely to develop several risk factors that could impact on contraceptive choice. It is important to take a good history that includes information on smoking, medications, medical history, menstrual problems, current contraception or methods used in the past. All this information will help direct towards appropriate methods.

Combined oral contraceptive

Women may be prescribed the COC up to the age of 50 years, provided they are completely free of risk factors. The COC increases the risk of stroke and VTE so in order for women to safely remain on the COC up to the age of 50, they must be non-smokers, have a BMI in normal range and have no evidence of hypertension, diabetes or migraine with aura. If starting a COC over the age of 40, a formulation containing <30mcg oestrogen should be considered and the BP should be measured six months after starting and annually thereafter. Women can be informed that there may be a small additional risk of breast cancer with COC use that reduces to no risk 10 years after stopping the COC.27 The COC contains oestrogen so it might help relieve menopausal symptoms and there is some evidence in the literature to support this. There is limited evidence to suggest that the COC may help maintain bone mineral density. The COC provides a protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancer that continues for 25 years or more after stopping.27

Progesterone only pill

The POP is a very safe option in women over 40, and is a particularly good option in women over 40 in whom oestrogen is contraindicated for medical reasons or who are concerned about the risks associated with oestrogen. Data from the WHO suggests that there is little or no increased risk of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction or breast cancer associated with POP use.27 A woman can remain on the POP until the age of 55 or until menopause is confirmed.12

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate

The FSRH suggests that the maximum age for using DMPA is 50. Women over 45 are UK MEC-2 for using this method, meaning that the benefits outweigh the risks. However, it seems sensible to encourage women to stop DMPA at 45 as this will give time for bone density to fully recover before the natural decline in bone density commences with the menopause. DMPA has a greater effect on lipid metabolism then other progesterone methods and so should be prescribed with caution in women with cardiovascular disease.27

Long-acting methods of contraception

Menstrual problems are common in women over 40 and the Lng-IUS (Mirena) which is licensed as a treatment for menorrhagia is being used increasingly for this indication. Lng-IUS is licensed for five years of use as a contraceptive. Randomised trials show that Lng-IUS provides effective contraception for up to seven years. The FSRH has recommended that women who have the Lng-IUS inserted at or after the age of 45 years and are amenorrhoeic, may retain the device until the menopause is confirmed.27

The Lng-IUS may also be used to provide endometrial protection in conjunction with oestrogen hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The benefit of this is that a woman with a Lng-IUS in situ who develops menopausal symptoms may leave the Lng-IUS in situ and commence oestrogen-only HRT.27 Lng-IUS has a failure rate comparable to sterilisation and thus offers a reliable alternative to sterilisation in women who are considering this method.13,28

The copper IUD is a really good cheap option, ideally suited to women with light periods who want a hormone free method. The gold standard Cu T 380 device lasts for 10 years, however it is accepted practice that a woman who has a copper IUD inserted at the age of 40 or over can retain the device until menopause is confirmed.27

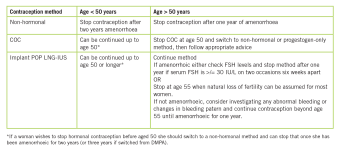

When to stop contraception

Menopause is usually diagnosed after one year of amenorrhoea, if aged over 50 and after two years of amenorrhoea if aged under 50. Women using non-hormonal contraception (barriers or Cu IUD) can stop contraception after two years of amenorrhoea if aged under 50 and after one year of amenorrhoea if aged over 50. However, if women are using hormonal contraception, making the diagnosis can be more challenging.

Women using Lng-IUS, POP or a progesterone implant cannot rely on the presence of amenorrhoea to diagnose menopause. However, FSH levels can be used to help diagnose menopause in women over the age of 50 who are using progesterone hormones. If a woman over 50 is amenorrhoeic on progesterone hormones, check two FSH levels six weeks apart and if both FSH levels are raised (>30IU) you can tell her she is menopausal and she can stop contraception after one year.27 FSH levels cannot be used to diagnose menopause in women under 50 on progesterone hormones or in women on the COC. Table 1 summarises the advice for stopping contraception.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)