MENTAL HEALTH

Alcohol dependence – issues for primary care

We should maintain a high index of suspicion for the contributory or causative role of alcohol in a variety of clinical presentations

October 1, 2013

-

As citizens and as healthcare professionals we are all too aware of our nation’s unhealthy relationship with alcohol. The problem we face is a growing health and social crisis, costing an estimated €3.7 billion a year in health, public order and other costs.1 But the cost of alcohol extends beyond monetary amounts. The figures are stark; alcohol is directly responsible for one in three road crash deaths and 1,200 cases of cancer each year in Ireland.2

Alcohol also has a significant effect on mental health, with alcohol-related disorders being the third most common reason for admission to Irish psychiatric hospitals between 1996 and 2005. In addition to this, excess drinking has severe social implications with alcohol being a contributor to a staggering 97% of public order offences according to the Garda PULSE system.

With the hazardous effects of alcohol so clear and well documented, assessing and attempting to change the harmful drinking attitudes of all of our patients needs to become as commonplace as checking blood pressure.

Common clinical presentations

Some patients will self-present for help and advice around alcohol use, but for those less forthcoming, the following presentations should raise a high index of suspicion:3

Psychiatric

- Amnesia, memory disorders and dementia

- Anxiety and panic disorders

- Depressive illness

- Deliberate self harm

- Apparent treatment resistance

Social

- Marital disharmony and domestic violence

- Child neglect

- Criminal behaviour

- Complications of unsafe sex

- Financial problems

- Homelessness

Occupational

- Impaired work performance and accidents

- Poor employment record

Physical

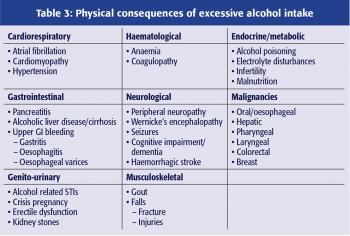

Physical consequences as outlined in Table 3.

Alcohol dependence syndrome

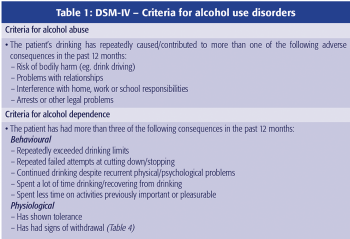

Drinking despite adverse consequences constitutes an alcohol use disorder.4 Current criteria (Table 1), according to the DSM-IV, differentiate abuse from dependence but following recent research the new DSM-5 criteria will amalgamate the two disorders into one continuum, ranging from mild to severe.

Assessment

When at-risk drinking is suspected, assessment should include:

- Full history and physical examination

- Mental state examination

- Assessment for consumption pattern

- Assessment for criteria of alcohol-use disorders

- Screening/examination for

– Withdrawal (Table 4)

– Alcohol-related health problems (Table 3)

– Non-alcohol-related health problems

– Social problems.

When addressing a patient’s drinking problem it is also useful to ask about prior treatment of alcohol abuse, attempts to cut back and periods of sobriety. Careful questioning on the circumstances around recurrent drinking and relapses5 can help to identify triggers; providing advice to avoid these triggers can reduce the risk of relapse.

Risk drinking

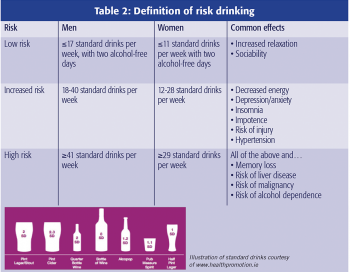

In Ireland, risk drinking is defined as drinking more than an average of 17 standard drinks a week for a male or 11 for a female. But the risk of harmful physical consequences of alcohol consumption exists on a spectrum where risk of consequences increases with units per week consumed (Table 2).

Physical consequences

There is a large number of conditions to which alcohol is a contributory or causative factor. The most common of these are listed systematically in Table 3.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

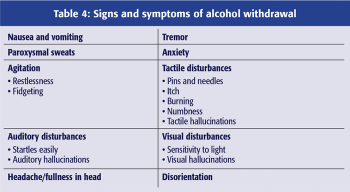

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is due to hyperexcitability of the brain following a sudden drop of blood alcohol concentration. Its signs and symptoms are listed in Table 4. Severity of the syndrome can vary from mild, with symptoms such as sleep disturbance and anxiety, to severe and life-threatening, manifested by seizures and death. First signs and symptoms occur within hours of the last drink and peak within 24-48 hours. In most alcohol-dependent individuals they are mild to moderate, and disappear within five to seven days after the last drink.

Delirium tremens

Commonly referred to as the DTs, delirium tremens is the most severe form of alcohol withdrawal. It can progress to cardiovascular collapse and is a medical emergency. It is characterised by:

- Nightmares

- Agitation, anxiety and paranoia

- Global confusion and disorientation

- Tremor

- Visual, auditory and tactile hallucinations

- Fever

- Autonomic hyperactivity.

DTs can occur between three and 10 days after the last drink taken, occur in 5-10% of patients with alcohol dependence syndrome, and carry a mortality of 5-15% with treatment and up to 35% without treatment.

Psychiatric consequences

Alcohol-related disorders accounted for one in 10 first admissions to Irish psychiatric hospitals in 2011 and the link between alcohol use and psychiatric illness is well documented. But the difficulty when discussing the psychiatric consequences of alcohol is distinguishing between cause, effect and comorbidity.

Alcohol has a number of psychiatric consequences, many of which mimic psychiatric disorders them-selves, such as symptoms of depression and panic disorder. Conversely, we must not forget that many patients with psychiatric disorders may turn to alcohol as a method of self-medication and escape. Because alcohol can potentially mask or mimic signs and symptoms of mental disorders, it can often create a real diagnostic conundrum.

Management

Most alcohol-use disorders can be effectively managed in the primary care setting with further supports available in the community. Some patients should be considered for referral to their local psychiatric services or substance abuse programmes. Rarely, patients require inpatient hospital detoxification. Outpatient care has been proven to be equally as effective as inpatient treatment6 with the exception of cases with complicating factors. Management plans can be decided based on:

- Whether the patient has developed alcohol dependence

- Whether the patient has withdrawal symptoms•

- Whether the patient has factors that may complicate the withdrawal or cessation process.

Brief interventions

Brief interventions are extremely effective in a primary care setting. They have been shown to reduce consumption in hazardous drinkers without alcohol dependence and to reduce alcohol-related harms and mortality.7

Key components of brief interventions:

- Informing patients of their alcohol risk category and the potential harm associated

- Assessing a patient’s readiness and planting seeds for change

- Establishing a new goal and giving advice on how to achieve it.

Supervised withdrawal in primary care

All withdrawals need general support and a proportion will need pharmacotherapy to modify the withdrawal-induced neuroexcitability. Signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal should be assessed (Table 4) and assigned a score depending on whether they are mild to severe. The scores are added up to give an Alcohol Withdrawal Score (AWS). The most widely used tool example is the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA-Ar)8 which grades withdrawal from mild to severe.

Most withdrawals can be managed safely and effectively at home under the supervision of the GP, but referral to medical or psychiatric services should be considered under the following circumstances.9

Consider A&E or medical services when:

- Confusion or hallucinations in any modality

- History of complicated withdrawal

- History of seizure disorder

- History of medications lowering seizure threshold

- Acute physical concurrent illness

- Uncontrollable withdrawal symptoms.

Consider psychiatric services or substance abuse programmes when:

- Acute psychiatric illness or suicidality

- Daily consumption of >20 standard drinks

- History of failed home-assisted withdrawals

- Polysubstance abuse.

Supplementation and symptomatic pharmacotherapy

Vitamin supplements, such as thiamine, should be offered as prophylaxis against Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Adequate fluid intake should be encouraged to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance. Paracetamol, metoclopramide and antihistamines may be useful in alleviating withdrawal symptoms.

Cautious use of benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used drugs for management of withdrawal. Chlordiazepoxide is the drug of choice in uncomplicated withdrawal as it has relatively low dependence-forming potential.10 In the community a fixed-dose regimen should be used:

- The starting dose of benzodiazepine should be selected once severity of alcohol dependence is assessed (clinical history, number of units per drinking day, score on CIWA-Ar)

- The dose is then tapered to zero over seven days.

Mild alcohol dependence usually requires small doses of chlordiazepoxide or may be managed with no medication. A typical regimen for moderate dependence might be 10-20mg chlordiazepoxide QDS, reducing gradually over five to seven days. Severe alcohol dependence usually requires referral for specialist or inpatient treatment.

Examples of fixed dose regimens can be found based on NICE guidelines at: www.nice.org.uk The NICE clinical guidelines GC10011 and GC11512 are useful to refer to and, for community-based management of withdrawal, suggest:

- Prescribing chlordiazepoxide for instalment dispensing, with no more than two days medication supplied at any time

- Monitoring the patient every other day

- Suggesting that a family member/carer oversees the administration of medication.

Management outside primary care

Further services are available in various formats nationwide that provide a supportive environment for achievement and maintenance of sobriety:

- Community-based addiction counselling

- Intensive outpatient programmes

- Residential programmes

- Group therapy/meetings

- Individual therapy.

Pharmacotherapy

According to recent evidence, relapse prevention medication should be considered for all alcohol dependent patients who wish to become abstinent.13 Recommended medications13 for preventing relapse and maintaining abstinence include:

- Acamprosate, which can be used to improve abstinence rates. Since there is evidence that it reduces alcohol consumption, if the patient starts drinking, it should be continued provided there is overall patient benefit. Avoid in renal impairment with creatinine clearance <30ml/min. Recommended dose – 666mg PO TDS (333mg PO TDS renal dose necessary in renal impairment)

- Naltrexone can be used to reduce risk of relapse. However, there is less evidence to support its use in maintaining abstinence. It should not be used with opioid analgesia. Recommended dose – 50mg OD PO

- Disulfiram is effective if intake is witnessed. There is less evidence base than for acamprosate and naltrexone. It should be offered as a treatment option for patients who intend to maintain abstinence, so long as there are no contraindications (eg. use of alcohol, treatment with metronidazole, heart disease). Must monitor LFTs and avoid alcohol in diet, toiletries etc. Recommended dose – 125-500mg PO OD.

The Irish Medicines Board website www.imb.ie has product datasheets for these medications.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)