PAIN

Chronic pain: current and the future management options

The diagnosis and management options for chronic pain – a condition which affects 13% of the population – are discussed

December 8, 2015

-

In its most benign form pain warns us that something isn’t quite right, that we should take medicine or see a doctor. At its worst, however, pain robs us of our productivity, our well-being, and, for the many people suffering chronic pain, their very lives.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines chronic pain as: ‘‘pain which persists past the normal time of healing… With non-malignant pain, three months is the most convenient point of division between acute and chronic pain”.

Chronic pain presents a major challenge to the citizens and the economy of Europe; one in five Europeans (19%) suffer from chronic pain, with most experiencing it for more than two years and some people enduring it for up to 20 years or longer. In Ireland 13% of the population suffer chronic pain.1 Annually E300 billion is spent in Europe on chronic pain management, representing 1.5-3% of gross domestic productivity (GDP). On average patients with chronic pain make seven visits to healthcare providers annually, with 22% making more than 10 visits. Despite this a quarter (22%) of individuals wait one to five years for a diagnosis/reason for their pain. It is not surprising therefore that most patients are dissatisfied with the time it takes to get adequate management of their pain.

Diagnosing chronic pain

Pain is a complex perception that differs enormously among individual patients, even those who appear to have identical injuries or illnesses. There is no test to measure the intensity of pain, no imaging device to show pain, and no instrument to locate pain precisely. The best aid to diagnosis is the patient’s own description of the type, duration and location of pain. Defining pain as sharp or dull, constant or intermittent, burning or aching may give the best clues to the cause of pain. The description of pain taken by the physician during the preliminary examination often influences the direction of the future management. Broadly there are three different sub-types of pain:

- Neuropathic

- Nociceptive

A combination of both, each of which responds to different treatments.

There are several validated questionnaires that can be used to focus on the particular pain type such as the McGill pain score and the neuropathic pain scores, which enable pain patterns to be identified.

Like every chronic illness, having chronic pain may also result in physical and psychological disability and is associated with serious co-morbidities such as anxiety and depression. The negative impact of chronic pain frequently extends beyond the patient to affect loved ones and dependants. The Pain Proposal survey (2006)1 reveals:

- 27% of people with chronic pain feel socially isolated and lonely because of their pain

- 50% worry about the effect of their chronic pain on their relationships

- 29% worry about losing their job

- 36% say their chronic pain has a negative impact on their family and friends.

People with chronic pain frequently feel their condition is compounded by a lack of understanding among the general public: nearly two-thirds (62%) of patients feel that public understanding and awareness of chronic pain is low.

The complexities involved in measuring chronic pain, with its differing manifestations and causes, can make it difficult to diagnose the root cause of an individual’s pain or define how best to manage it. Never the less, some investigations can be used to find the potential cause of pain. These include:

- Electrodiagnostic procedures including electromyography (EMG), nerve conduction studies and evoked potential (EP) studies, which aim to assess the muscles or nerves that are affected by weakness or pain

- Imaging, especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which provides physicians with a useful tool to identify nerve compression or muscle injury

- X-rays of joints/bony structures

- Bone scans and ultrasound

- Biochemistry screening, tumour biomarkers

- Quantitative sensory testing.

Common causes of chronic pain

Chronic pain can be caused by a variety of physical or psychological factors. Physical causes include musculoskeletal, vascular and neurological conditions as well as injury to organs and tissues from surgical interventions or other diseases, such as cancer. Chronic pain can be nociceptive, neuropathic or a combination of both. Nociceptive pain is associated with tissue damage. Neuropathic pain occurs when nerves or part of the nervous system malfunction. If pain has a neuropathic element it can be resistant to some commonly used treatments and may require a different approach.

The most common location for pain is the back. According to market research conducted in five European countries in 2010, back pain accounts for 70% of cases of severe pain, 65% of moderate pain and more than half the cases of mild pain. The Pain Proposal survey1 of people with chronic pain listed back problems as the most common cause of chronic pain (55%), followed by joint pain and neck pain. Headache, migraine, arthritis, fibromyalgia, persistent post surgical pain are all at least twice as commonly reported as cancer pain.

The complexity of measuring pain and its different manifestations can make it difficult to establish the root cause of an individual’s pain or how best to manage it. As a result, healthcare for individuals with chronic pain can be fragmented and identifying the best treatment approach can take time.

Treatment strategies

Each patient should have an individualised multi-modal therapeutic regime that should concentrate on:

- Treating the underlying cause of pain whenever possible

- Using appropriate medicines as part of a pain management plan

- Provide regular analgesia (‘by the clock’), titrated to achieve best effects, in a way to improve the quality of life for each patient

- Recognise that therapeutic regimes need to be individualised with attention to detail and combined with psychological support, such as cognitive behavioural techniques

- Identify the importance of monitoring and evaluating for therapeutic and unwanted effects.

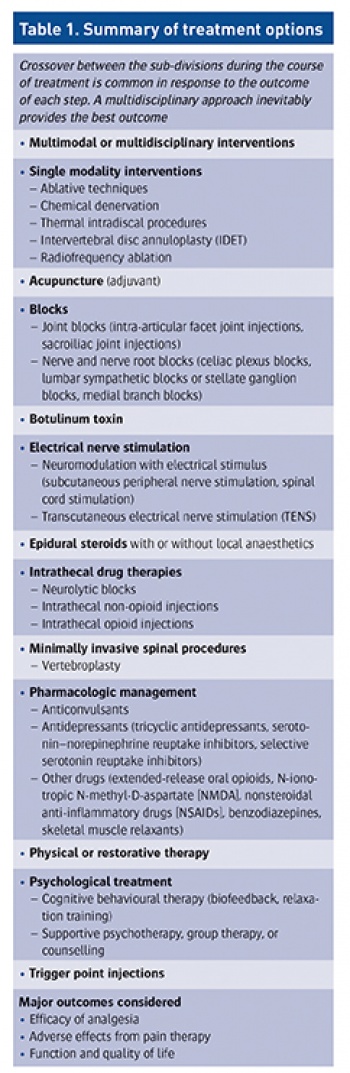

While there is no gold standard to treat every patient, in principle the treatment options can be divided into three main subdivisions:

- Interventional

- Non-interventional

- Physical/psychological.

Table 1 illustrates these options. The evidence suggests that cross-over between the sub-divisions during the course of treatment is common in response to the outcome of each step and that a multidisciplinary pain management approach inevitably provides the best outcome. Regular re-assessment is critical to ensuring positive progress continues at all stages of treatment. With appropriate goal setting, the clinical outcome for each individual should be set to include a reduction in pain intensity combined with improved function and/or quality of life.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)