GASTROENTEROLOGY

Coeliac disease: clinical presentations and diagnosis

The clinical presentations, diagnosis and pathology of coeliac disease are outlined by the gastroenterology team at Connolly Hospital

October 1, 2015

-

Coeliac disease is characterised by small intestinal malabsorption of nutrients after the ingestion of wheat gluten or related proteins from rye and barley, villous atrophy of the small intestinal mucosa, prompt clinical and histologic improvement following strict adherence to a gluten-free diet, and relapse when gluten is reintroduced.

It shows a marked geographic variation, with the highest incidence in western Europe. The condition is more common in Scandinavian and Celtic populations, where the prevalence has been reported to be as high as one in 99 and one in 122, respectively. These patients often have a genetic predisposition to coeliac disease, especially human leukocyte antigen class II DQ (HLA-DQ2) in 90-95% of patients, while the rest are (HLA-DQ8), (compared with approximately 35% of the general white population).1,2,3,4

Coeliac disease exhibits a spectrum of clinical presentations (see Table 1). Non-classical coeliac disease (atypical coeliac disease) is fully expressed gluten sensitive enteropathy manifested only by extra intestinal symptoms and signs, including short stature, anaemia, osteoporosis, and infertility.

Silent coeliac disease is fully expressed gluten-sensitive enteropathy usually found after serologic screening in asymptomatic patients. The atypical and silent variants are more common than classic or typical coeliac disease, which is fully expressed gluten-sensitive enteropathy found in association with the classic gastrointestinal symptoms of malabsorption. Patients with latent coeliac disease have normal villous architecture on a gluten-containing diet but, at another time, have had or will have gluten-sensitive villous atrophy. Patients with potential coeliac disease have never had a biopsy consistent with the disease but show characteristic immunologic abnormalities.

Refractory coeliac disease is defined as symptomatic, severe small intestinal villous atrophy that mimics coeliac disease but does not respond to at least six months of a strict gluten-free diet. This is a diagnosis of exclusion that is not accounted for by inadvertent gluten ingestion, other causes of villous atrophy, or overt intestinal lymphoma.3

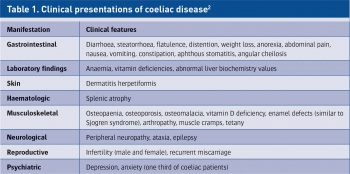

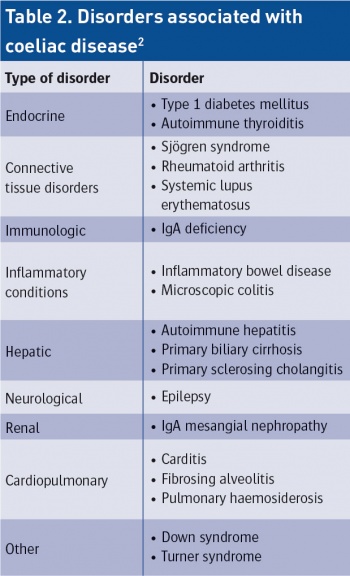

Adapted from Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Diagnosis of coeliac sprue. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 (Dec): 96(12): 3237-46(click to enlarge)

Adapted from Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Diagnosis of coeliac sprue. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 (Dec): 96(12): 3237-46(click to enlarge)

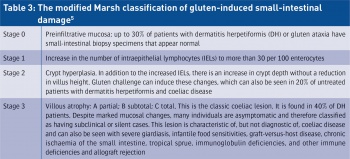

From Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Diagnosis of coeliac sprue. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Dec: 96(12):3237-46(click to enlarge)

From Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Diagnosis of coeliac sprue. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Dec: 96(12):3237-46(click to enlarge)

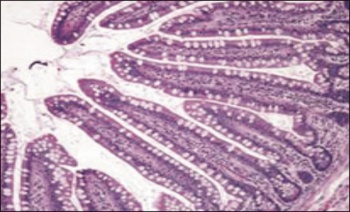

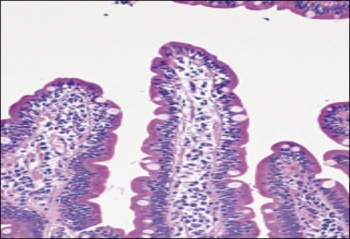

Figure 1. Small-bowel histopathologic findings in coeliac disease (from Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review 5th edition) (4) A - Normal findings (haematoxylin-eosin)(click to enlarge)

Figure 1. Small-bowel histopathologic findings in coeliac disease (from Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review 5th edition) (4) A - Normal findings (haematoxylin-eosin)(click to enlarge)

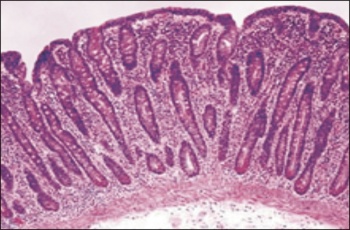

B - Intraepithelial lymphocytes alone as seen in an early March lesion of coeliac disease (haematoxyln-eosin)(click to enlarge)

B - Intraepithelial lymphocytes alone as seen in an early March lesion of coeliac disease (haematoxyln-eosin)(click to enlarge)

C - Classic histologic findings of coeliac disease, with marked villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis with a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the lamina proporia (haematoxylin-eosin)(click to enlarge)

C - Classic histologic findings of coeliac disease, with marked villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis with a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the lamina proporia (haematoxylin-eosin)(click to enlarge)