MENTAL HEALTH

Innovative ways to help increase access to CBT

Computerised CBT offers accessible and effective therapy for anxiety and depression

October 1, 2013

-

Despite strong evidence for its effectiveness, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is difficult to access, partially because there are not enough trained practitioners in primary and secondary care.1 The inaccessibility of CBT may be especially pertinent in Ireland due to our underdeveloped mental health services.2 In light of this, innovative ways to increase access to CBT may need to be explored. One such avenue is computerised CBT (cCBT), which refers to the delivery of CBT via the internet.

Main features of cCBT

Although cCBT can be delivered in ‘real-time’ via instant messaging, the majority of research has examined predetermined (syllabus-style) programmes consisting of interactive informational sessions and homework assignments.3 A cCBT programme can be completed on a purely self-help basis or it can be offered with assistance from appropriate staff members (eg. psychologists, counsellors). This assistance usually encompasses one of the following:

- Simple reminders to complete cCBT sessions

- Regular telephone calls that guide the service user through the course

- The provision of brief advice helplines.3,4

In rare cases, cCBT is delivered in one-to-one sessions, for example, the cCBT game for children with depression or anxiety called ‘Pesky Gnats’ (www.peskygnats.com).

The composition of individual cCBT programmes varies widely but most include one or more of the following aspects: education, quizzes, mood and thought diaries, activity planning, goal setting, and homework tasks. The total number of sessions can also vary but a recent review indicated a session range of five to 10.5 Most often, cCBT sessions are completed on a weekly basis but they can also be completed at a person’s own pace.5

Evidence behind cCBT for common mental health problems

Several large-scale meta-analyses have demonstrated that computerised psychotherapies (including but not limited to cCBT) are effective for a wide range of psychological difficulties.6,7,8 Focusing solely on cCBT for anxiety and depression (the two most common mental health problems in primary care), there have so far been three meta-analyses, all of which indicated that cCBT is effective.3,9,10

Moreover, these meta-analyses indicated that the average depressed or anxious person who avails of cCBT will fare better clinically than around three quarters of those who do not receive treatment.

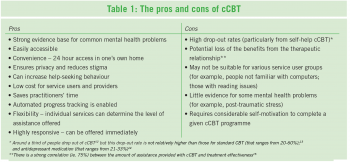

Alongside this good evidence, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends cCBT as a low intensity treatment for anxiety and depression that can be used in primary care.11 For the pros and cons of cCBT see Table 1.

Available cCBT programmes

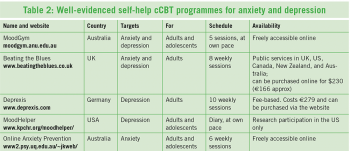

Despite the positive research surrounding cCBT, the quality of individual cCBT programmes is likely to vary because of the unregulated nature of the internet and the proliferation of therapy websites in recent years.16 Some high quality well-evidenced cCBT programmes for patients are highlighted in Table 2. These are available in English on the internet, for the treatment of anxiety and depression. It is worth noting that only two of the profiled cCBT programmes (ie. MoodGYM, moodgym.anu.edu.au and Online Anxiety Prevention, www.psy.uq.edu.au/~jkweb/) are currently freely accessible online to residents of Ireland. Of the two, MoodGYM has more evidence behind it.

As part of the piloting of stepped-care psychological services within primary care in Roscommon HSE West, MoodGYM is being offered to service users with assistance from primary care mental health practitioners. After an initial assessment session, MoodGYM and other self-help interventions are explained and offered to service users in a second session. Next, relevant service users are asked to complete MoodGYM over the course of six weeks and during this time, two brief telephone calls are provided to guide service users through the intervention. Finally, services users are offered a third session to assess progress and decide if higher intensity services (eg. group skills classes, one-to-one CBT) are needed. In this way, the therapeutic relationship is maintained yet the time of practitioners is protected because many of the routine tasks of CBT are covered by MoodGYM. Using the learning from this roll-out of MoodGYM, the local services will develop free-to-use depression and anxiety cCBT websites.

Conclusion

Whether provided on a purely self-help basis or with assistance, cCBT offers an effective treatment for common mental health problems in primary care. Self-help cCBT requires less practitioner time and is more easily accessible than assisted cCBT. However, more people drop out of self-help cCBT and less people benefit from it. This is most likely because of the absence of the therapeutic relationship that can be maintained in assisted cCBT. The availability of resources may determine which format cCBT is delivered in by different primary care services. If delivering cCBT via self-help, instructions on how to access and complete a given cCBT course could be provided in a simple information leaflet that could be given to service users by various primary care staff. If delivering cCBT with assistance, appropriate staff members (with appropriate mental health training) should familiarise themselves with a chosen cCBT course and determine the level of assistance that can be provided on a regular basis.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)