DERMATOLOGY

Management of localised viral skin infections

Herpes simplex and varicella zoster are the two most common localised skin conditions that present in general practice

August 1, 2013

-

The two most common localised skin conditions caused by viral infections are herpes simplex and varicella zoster.

Cold sores (herpes simplex virus type 1)

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 causes cold sores, which are characterised by recurrent eruptions of a vesicular rash that crusts over and heals completely without scarring over the course of one or two weeks. Although the lips are the most common area affected (herpes simplex labialis), cold sores can occur on any part of the body. The only other eruption to repeatedly come up in the same area would be a fixed drug eruption. This is very rare and not usually vesicular.

The first attack of HSV type 1 is usually in childhood and often asymptomatic. However, it may cause a painful stomatitis in the mouth and lips that can cause difficulty eating and swallowing (herpetic gingivostomatitis). This usually resolves spontaneously within one to two weeks without treatment.

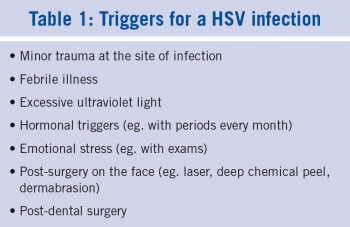

Once infected, the virus will remain dormant and resistant to treatment in the basal root ganglion for the rest of the patient’s life. It may erupt at any stage to cause the classical cold sores. There are many possible triggers for cold sores (see Table 1), but often they can erupt for no particular reason. Treatment is difficult as usually the damage is done as soon as the rash appears.

Avoidance of triggers is the best way to manage cold sores but this is not always possible. Treatment with topical antivirals such as acyclovir can be of some benefit but will only work if the treatment is started at the earliest possible stage; preferably at the tingling stage (if it occurs) before the visible vesicles are seen. It has to be applied five times a day for five days and for those with frequent attacks; having a tube at home or in their handbag is useful so that they can start treatment at the earliest possible time.

Once the vesicles have appeared it is questionable if topical acyclovir will help. There are very few good clinical trials on the value of topical acyclovir. It may well be that a simple anti-inflammatory with a topical antibiotic may be as effective or even more effective at this stage.

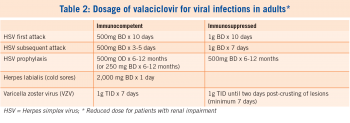

HSV type 1 can cause severe, extensive, painful, monomorphic vesicles and erosions with glands and a fever, especially in patients who have a background of atopic eczema (eczema herpeticum or Kaposi varicelliform eruption). For severe extensive infection, systemic antivirals should help but again should be started at the earliest possible stage in an attack (see Table 2).

For patients with frequent recurrent severe attacks of cold sores, prophylactic treatment with systemic antivirals may be necessary. This can also be used for patients who are at high risk of developing cold sores after procedures such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, laser treatment, chemical peels, dermabrasion, etc.

When HSV type 1 affects the finger, it can cause a herpetic whitlow, which can sometimes be an occupational hazard for dentists and dental assistants. This is why dentists should wear gloves for all oral examinations.

Genital herpes (HSV type 2)

Genital herpes is a much less common but more serious HSV infection, which is caused by a type 2 virus. Like cold sores, the diagnosis can often be made clinically, with the characteristic vesicular eruption recurring time and again in the same area (penis or vagina) and healing without scaring. The eruption is painful and can take a few weeks to heal. It is usually sexually transmitted and, like all STDs, the patient should have a complete STD screen and contact tracing, which is probably best carried out in an STD clinic, especially if it is a first attack. The diagnosis can be confirmed by taking swabs using special viral swabs, but it is only possible where there are fresh lesions. Treatment of genital herpes usually requires a systemic antiviral treatment to be started as early as possible in an attack. For those with frequent attacks, suppressive maintenance treatment with an oral antiviral medication for six to 12 months may be helpful.

Patients are infectious during an attack and so should avoid sex at this time. Childbirth during an attack of genital herpes could possibly infect the new born child. Once the lesions are fully healed, they are not usually infectious until the next attack of herpes.

Erythema multiforme

This is a hypersensitivity reaction typified by a generalised rash that has the characteristic target lesions (see Picture 1). HSV (cold sore) is the most common trigger. This can sometimes be associated with blisters, erosions and ulcers in the lips, mouth and genitalia, which can be painful and debilitating. The rash should clear spontaneously after a few weeks but can recur with every attack of cold sores in some patients. Treatment of erythema multiforme is usually with topical or oral steroids combined with systemic antivirals for a severe attack. Prevention may require treatment with long-term oral antivirals so as to prevent cold sores.

HSV may also trigger an attack of erythema nodosum with the characteristic red, tender, maculopapular, non-scaly rash on the front of the shins and sometimes on the forearms.

Chickenpox (varicella zoster)

Chickenpox (varicella zoster) is considered a harmless childhood viral infection that occurs in most children. It causes the typical generalised vesicular eruption and mainly affects the face and trunk. It can be associated with a low grade fever but most children recover spontaneously without complications within one to two weeks. It has an incubation period of 10 to 21 days. It is infectious from two days before the appearance of the rash until all the vesicles have crusted over, which usually takes five to 10 days. If a person has a severe attack or is immunocompromised (diabetes, chemotherapy, leukaemia, HIV, etc), they should be treated with systemic antivirals. The varicella virus can be harmful to an unborn child, so children with chickenpox should avoid contact with pregnant women if possible.

If a pregnant woman or an immunocompromised person is exposed to a case of chickenpox and their immune status is unknown, they should be considered for varicella zoster immune globulin and systemic antivirals.

Chickenpox can leave small punched out scars, which can be unsightly and permanent, particularly if they occur on the face. Prevention of scarring may be helped by using a topical anti-inflammatory with an antibiotic on the facial lesions twice a day for seven to 14 days.

Shingles (herpes zoster)

Once chickenpox clears, the virus will remain dormant in the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord. It can remain dormant there for the rest of the patient’s life. It may be reactivated spontaneously or by various triggers and when it erupts it causes shingles. This can occur at any age but is more common and more problematic in older people.

Shingles usually presents with the characteristic unilateral, vesicular or bullus eruption running in a dermatomal distribution (eg. one side of the face, one side of the chest, or down one arm or one leg). It can be painful and sore and usually settles spontaneously in two to three weeks. Occasionally it can be very inflammatory and leave permanent scars and chronic pain and tenderness in the area, which lasts more than one month (see picture 2). This is known as postherpetic neuralgia. It is more common in patients over the age of 50.

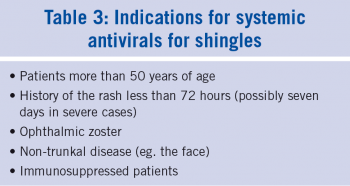

There is some evidence that treating shingles with oral antivirals at an early stage may be lessen the incidence and severity of postherpetic neuralgia and so systemic treatment should be considered for shingles, particularly in those over the age of 50 once it can be started within 72 hours from the first appearance of the rash (see Table 3). There is some limited evidence that systemic treatments with antivirals may be effective even up to seven days after the onset of the rash, particularly in the high risk groups.1

Shingles can be preceded by pain or discomfort in the area involved for a few days before the rash appears. The prodromal pain can be confused with many other conditions, depending on where the eruption occurs: For example, if on the face, it may be confused with migraine; on the chest – myocardial infarction, and on the abdomen – cholecystitis or appendicitis, etc.

When shingles affects the ophthalmic branch of the facial nerve, the eye could be in danger of corneal scarring and so an ophthalmic opinion should be sought immediately.

The varicella zoster virus (VZV) may be shed from shingles lesions and can cause chickenpox in a non-immune child or adult. Despite popular myth, it is not possible to get shingles from another patient with shingles. However, clusters of cases with shingles have been reported. It is suggested that contact with someone with chickenpox or shingles may cause one’s own virus to reactivate.

Postherpetic neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia causes neuropathic pain which can be described as burning, shooting, itching or stabbing hypersensitivity in the area, which can last for more than one month after an attack of shingles. This can be a very painful and debilitating condition, particularly when it occurs on the face. It does not usually respond to standard analgesics such as paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. Tramadol may be more effective in some patients. Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline taken at night can be very helpful, particularly if there is night pain or insomnia. The dose should be started at 10mg one or two hours before going to bed, and gradually increased until the patient has a good night’s sleep without drowsiness the following morning.

However, more specific treatments with antiepileptic drugs, such as gabapentin or pregabalin, may be necessary.2 These should be started at a low dose and gradually titrated up until a therapeutic response is obtained or side effects ensured against. Topical treatments such as lidocaine patches are of limited value and are not practical on the face. Topical capsaicin, which is derived from chilli peppers, can act as a counterirritant, which may be of help in some patients.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) or nerve blocks may be required in severe cases. Combining treatments such as pregabalin, amitriptyline and capsaicin cream may be tried, but at this stage the patient should probably be referred to a pain clinic. In some countries there are vaccines against chickenpox for children and against shingles for people over the age of 50.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)