OBSTETRICS/GYNAECOLOGY

WOMEN’S HEALTH

Neural tube defects: where are we now?

The supplementation strategy for the primary prevention of NTDs has not succeeded to date

April 11, 2018

-

Neural tube defects (NTDs) comprise a group of congenital malformations associated with the failure of closure of the neural tube, which is normally complete by day 28 of embryonic development. NTDs include anencephaly, encephalocele and spina bifida. They are the second most common major congenital anomaly and, in contrast to other congenital anomalies, primary prevention of NTDs is possible with folic acid supplementation.

NTDs affect approximately one in 1,000 pregnancies in Europe.1,2 However, the burden of illness with NTDs is high in Ireland in comparison to other European countries because we have a consistently high fertility rate and twice the rate of infants with spina bifida live-born, with lifelong consequences.1

It is estimated that two-thirds of NTDs are preventable by folic acid supplementation. The other third are associated with factors such as poor glycaemic control in the first trimester, hyperthermia, maternal obesity, aneuploidy or genetic disorders.3

Background

In 1991-92, two landmark randomised controlled trials reported that folic acid supplementation commenced before pregnancy prevented the occurrence and recurrence of NTDs.4,5 Since 1993, therefore, national recommendations in Ireland and other countries advised women to start folic acid 400µg orally before pregnancy and to continue for the first trimester.6 Women considered at higher risk of NTDs (for example, women with diabetes mellitus, obesity at the first antenatal visit, a previous pregnancy complicated by an NTD, a family history of NTDs, inflammatory bowel disease, women taking certain antiepileptic medications or folate antagonists) were advised to start 5mg folic acid per day oral dosage, which requires a prescription from a doctor.7

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in a recently updated clinical guideline advised that higher dose folic acid is required at least three months pre-pregnancy to bring about a 70% risk reduction in high risk cases.3,8

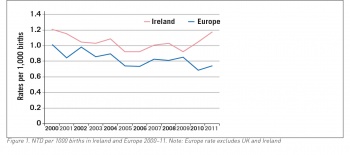

However, since 1993 the prevalence of NTDs in Ireland has not fallen and may even have increased (see Figure 1). A comprehensive national audit of 225,998 total births in the Republic of Ireland found the overall rate of neural tube defects was 1.04/1,000 births with no improvement in trends since the guidelines on supplementation were first published.9 This has been confirmed again by a similar audit of births nationally in 2012-15.9

Furthermore, data from the EUROCAT registries have shown no improvement in NTD prevalence rates in the UK or Europe over the past 25 years.10

Irish research

The supplementation strategy for the primary prevention of NTDs has, to date, not succeeded. There are a number of possible reasons for this. Half of pregnancies worldwide, including in Ireland, are unplanned.11 Among women, especially in immigrant or educationally-disadvantaged groups, there is a lack of knowledge that to prevent NTDs, folic acid should be commenced before pregnancy.12

The Safefood report released in December 2017 entitled The folate status of pregnant women in the Republic of Ireland – the current position reported on a survey of 564 women in early pregnancy. Of the 331 women who did not take folic acid pre-pregnancy, 76.4% stated that they did not expect to get pregnant and 35.0% did not know that they needed to take folic acid before becoming pregnant.12,13

In a prospective observational study from the UCD Centre for Human Reproduction, it was shown that most women who start folic acid during pregnancy do not commence supplementation until their pregnancy test is positive.14 Of the 245 women who commenced it after their last menstrual period, 84% commenced it more than four weeks after their last menstrual period which coincides with neural tube closure.14

In the recent Safefood report dietary folate intake in women (n = 392) presenting for antenatal care was inadequate, with a median total intake of 235.2µg.13 The WHO recommends a daily intake of folate for pregnant women of 600µg to sustain cellular development, which is rarely met even by women taking a healthy, folate-rich diet.15

The Safefood report found 98.2% of women are taking folic acid supplementation at the time of the first antenatal visit, which is high compared to previous national surveys and shows the willingness of women to comply. Less than half (42.8%) of the women, however, commenced folic acid supplementation before pregnancy and only 24.9% were taking it for more than 12 weeks beforehand. At the time of presentation for the first visit, therefore, the opportunity to prevent NTDs had often been lost.

Of the women who commenced folic acid four to eight weeks before conception, 78.4% achieved the red blood cell (RBC) folate level of >906nmol/L (measured at the first antenatal visit) compared to just 53.3% of those who commenced folic acid four to eight weeks after conception.13 (906nmol/L is considered the optimal RBC folate level threshold above which there is a risk reduction of NTDs to <8/10,000 live births).16

The inconsistent public information on folic acid supplementation, with differing guidelines nationally and internationally, may be another factor. A review of 20 European national guidelines on the use of folic supplementation found that only four of the 20 guidelines advised that women commence it preconceptually, while none made any recommendation on when to stop during pregnancy.17

It is also notable that voluntary fortification of food with folic acid is decreasing in Ireland. A Dublin study found that of the 346 products fortified with folic acid in 2004, only 152 (45%) were fortified in 2014.18

As the process is voluntary, food manufacturers do not have to inform the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI) of changes to its levels in products. Despite recommendations in reports from the FSAI in 2006 and 2016, mandatory fortification has not been implemented in Ireland or indeed throughout the European Union. Given the mobility of food and food ingredients across national borders, implementation of mandatory fortification is challenging and is likely to become more so post-Brexit.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)