CANCER

NUTRITION

Nutritional management in head and neck cancer

Most patients with head and neck cancer find having a feeding tube life changing and limiting in carrying out their daily activities

September 1, 2023

-

Head and neck cancer (HNC) include cancers of the lips, mouth, nasal cavity, paranasal sinus, pharynx, and larynx. Patients with HNC are at increased risk of malnutrition due to tumour location and consequences of treatment. Patients receiving treatment for HNC are likely to experience significant weight loss and reduction in physical activity, skeletal muscle mass, muscle strength, and overall physical performance.1,2

The high prevalence of malnutrition in patients with HNC negatively impacts patient outcomes. It has been reported that sarcopenia occurs in 6.6% to 70.9% of HNC patients and malnutrition in 30% to 50% of patients.3,4,5 A review by Cook et al described the important role of the dietitian in the head and neck cancer pathway.6 Malnutrition and unintentional weight loss can occur at any stage of the patient pathway, and up to 60% of HNC patients have experienced this before commencing treatment,7 increasing to up to 86% at the end of chemo/radiotherapy.8

Recent studies found that patients who are overweight or obese at diagnosis can be at a higher risk of malnutrition during treatment.9 Malnutrition is adversely associated with treatment tolerance, wound healing, surgical complications, morbidity, mortality, quality of life and survival.10 Furthermore, weight loss is a predictor for poor survival and treatment tolerance.11,12

Specialist support

HNC patients benefit from nutritional support provided by a specialist dietitian. When oral intake is insufficient, a feeding tube is often required. This is usually due to progressive dysphagia, post-operative dysphagia or if required on chemo/radiotherapy due to treatment toxicity. If enteral feeding is required for more than three to four weeks, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is the most common feeding tube used. This is associated with fewer treatment disturbances and can improve clinical outcomes and survival.13

Differences occur across centres nationally and internationally regarding prophylactic versus reactive enteral feeding on chemo/radiotherapy. The evidence base for placement of prophylactic gastrostomy tubes before chemo/radiotherapy remains inconclusive.14,15 There are some guidelines available to assist in appropriate decision-making, which considers tumour stage, site, age, nutritional status, dysphagia, performance status and potential toxicities as a result of planned treatment.9,16,17,18

Kao et al recently described the impact of prophylactic PEG versus reactive feeding on chemo/radiotherapy in over 11,000 patients with HNC. Timing of PEG placement had no effect on BMI changes and overall survival. However, prophylactic PEG placement decreased hospital admission rates compared to reactive feeding.19 Further research on the optimal indications for prophylactic PEG placement is required.

Quality of life

Quality of life is an important factor to consider in all cancer patient pathways but it is of particular significance to HNC patients due to changes in physical appearance, difficulties eating and drinking, difficulties with speech and side effects of treatment. A study following patients five years after diagnosis reported improvements in sleep, pain, global health status, and emotional function. However, problems with dry mouth, dentition, sense of smell and taste continued to worsen over time.20 Corry et al compared HNC patients receiving nasogastric tube (NGT) feeding and PEG feeding and found no differences in physical condition or overall quality of life. Patients on PEG feeding lost less weight six weeks post treatment, but at six months post treatment there was no difference in weight loss between NGT and PEG groups.21

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 is a widely used cancer-specific quality of life tool. A review using these questionnaires showed patients described family, pain, physical appearance, being able to eat and drink, and being able to eat and drink together as important areas of quality of life.22 In a study by Ehrsson et al assessing quality of life of patients on enteral feeding, there were no differences in quality of life between the patients who were eating orally versus enterally fed. Many patients expressed positive aspects about receiving enteral nutrition as it reduced the burden of needing to maintain nutrition orally when it was difficult. The negative aspects described enteral feeding as time-consuming and for some it was difficult to manage to take all feeds prescribed.

This study also compared quality of life in NGT versus PEG, where patients on PEG feeding found the tube uncomfortable, caused sleep difficulties and limited social activities. For patients with NGT, they reported embarrassment due to the tube being visible, which they felt also limited social activities.23 In the study by Corry et al, patients with NGT described pharyngeal ulceration, inconvenience with NGT, altered body image, and interference in family and social life when comparing NGT with PEG. There were no differences in quality of life between the two groups one week after tube insertion or six weeks after completion of treatment.21 However, Sadasivan et al showed significant differences six weeks post insertion regarding weight change and quality of life in favour of PEG.24

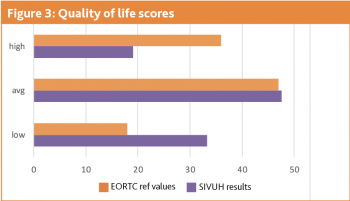

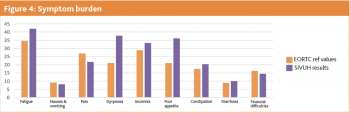

At the South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital (SIVUH), we conducted two studies on patients with HNC on home enteral feeding. Study 1 was a retrospective audit investigating reasons for gastrostomy tube insertion in HNC patients, and Study 2 investigated quality of life of HNC patients receiving home enteral nutrition.

Study 1

The aim of this study was to determine the reasons for gastrostomy tube insertion, duration of enteral feeding and nutritional outcomes in patients with HNC under the care of SIVUH.

Methods

Data were collected prospectively from a patient database on HNC adult patients who had a gastrostomy tube inserted from January 2022 to December 2022. Accessing dietetic record cards enabled identification of patient demographics, disease demographics, weight changes, oncological treatment, reason for insertion and enteral feeding duration.

Results

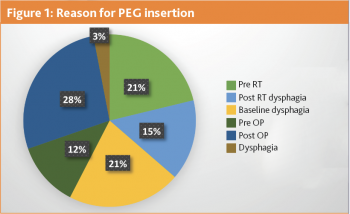

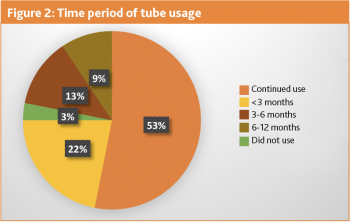

A total of 32 new gastrostomy tubes were inserted in SIVUH in 2022. Eight tubes were placed prophylactically and 24 were used immediately (see Figure 1). Sixteen patients had lost weight (range -0.01% to -17.8%). However, four patients weight remained stable and 12 patients gained weight (range 0.7% to 20.4%). Average weight change was 0.4% loss. Three patients did not use their gastrostomy tube and these tubes were placed prophylactically pre radiotherapy. Just over half of these patients (53%) are still using their gastrostomy tubes and are active on home enteral nutrition (see Figure 2).

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)