CANCER

Palliative care and cancer – earlier is better

Early involvement of palliative care services has been shown to improve quality of life and even aid survival

November 8, 2013

-

The specialty of medical oncology has progressed at a phenomenal rate over the past few decades. Major advances in combined and targeted therapies have resulted in dramatic improvements in survival rates for many cancers.1 However, this impressive progress in cancer disease management is not always accompanied by an equal focus on addressing the physical, psychosocial and existential challenges consequent on living with advanced cancer.2

Cancer is often accompanied by significant symptom burden, psychosocial distress, and poor quality of life.3 For more than a decade, the World Health Organisation has defined palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.

“Palliative care is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications”.4

The overall objective of palliative care is to anticipate, prevent and reduce suffering.5

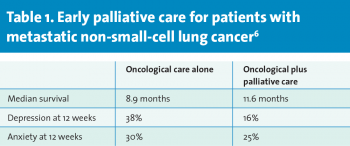

In a 2010 landmark paper, Temel et al demonstrated that in a series of patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the early introduction of palliative care positively impacted on patients’ quality of life and may even have conferred a significant survival benefit.6

Many organisations, including the WHO, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), support the introduction of palliative care services as appropriate at an early stage in the patient’s illness. Oncologists have a key role to play in integrating palliative care services at the earlier stages of malignant disease.

However, it cannot be left to oncologists alone. We need a major shift in attitudes amongst all healthcare professionals and the general public before palliative care becomes accepted as an integral part of good quality care from the initial diagnosis. Currently, there is a widespread misconception that palliative care involvement is restricted to the very end stages of disease and only at a time when all other disease-modifying interventions have failed.

Early palliative care

Palliative care includes the appropriate care of patients at the very end of life, but end-of-life care does not define palliative care. It is applicable at each and every stage of the patient’s journey.

Patients must not be presented with an ‘either/or’ option, but must have the facility to avail of high-quality oncology services in conjunction with skilled, specialist palliative care.

What really is palliative care?

In some of the literature, a distinction is drawn between supportive care, palliative care and terminal or end-of-life care. Supportive care aims to optimise the comfort, function and social support of the patient and family at all stages of the illness; all patients need this, continuously.

Palliative care aims to optimise the comfort, function and social support of the patient and their family when cure is not possible; it is focussed on the special needs of patients whose disease is incurable.

Terminal care or end-of-life care is palliative care when death is imminent.7

These distinctions are not universally applied and, indeed, the WHO definition of palliative care embraces all of these various elements.

The overall objective of these various interventions and supports, irrespective of how they might be classified or represented, is to enable each patient to live the life they choose to live, with the best possible degree of comfort and quality, in the setting of their choice for the duration of their natural life.

Proven benefit

The 2010 Temel et al study in the New England Journal of Medicine6 created much discussion and debate amongst the palliative care and oncology communities worldwide.

This study of 151 patients compared the effects of offering early palliative care and standard oncology treatment versus standard oncology treatment alone amongst a group of patients with newly diagnosed metastatic NSCLC.

Health-related quality of life and mood were assessed at baseline and again at 12 weeks. Eligible patients were enrolled within eight weeks of diagnosis and randomly assigned to one of two groups.

Patients who were assigned to the early palliative care group met with a member of the palliative care team within three weeks of enrolment and at least monthly thereafter in the outpatient setting.

Patients who were assigned to the standard care group did not meet with the palliative care team unless the patient, the family, or the oncologist requested a meeting.

Patients randomly assigned to the early palliative care intervention group had significantly higher scores for quality of life measures compared to the standard group. These patients also showed fewer signs of depression. However, perhaps the most surprising finding was that the average survival rates for patients in the early palliative care intervention group were prolonged by 2.7 months. The key findings are summarised in Table 1.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

“…perhaps the most surprising finding was that the average survival rates for patients in the early palliative care intervention group were prolonged by 2.7 months” (click to enlarge)

“…perhaps the most surprising finding was that the average survival rates for patients in the early palliative care intervention group were prolonged by 2.7 months” (click to enlarge)