CARDIOLOGY AND VASCULAR

Patient management after abnormal ABPM

A follow-up practice study that highlights how GPs can use their judgement to tailor guidelines to patient need

March 23, 2017

-

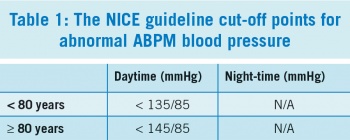

Current guidelines from the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2011) and the European Society of Hypertension and European Society of Cardiology (ESH/ESC 2013) recommend the use of ambulatory blood pressure measurement (ABPM) in the diagnosis and management of hypertension.1,2

We aimed to follow up a previously undertaken study that reviewed ABPM use by one general practice over a three-year period from January 1, 2010 to December 17 2012.3 We reviewed the practice one year later, from November 1, 2013 to 31 October 2014, to identify improvements in practice adherence to NICE guidelines for clinical management of primary hypertension, and to understand why non-adherence persists in some cases.

All patients who had an ABPM recording were included in the study. We analysed practice ABPM records using NICE guidelines and identified all abnormal results. We then reviewed how patients with abnormal ABPM results were managed. Where management did not adhere to guidelines, we quantified the variance above guideline limits in millimetres of mercury (mmHg). Finally, we reviewed whether the clinical rationale for non-adherence to guidelines was documented in patient notes.

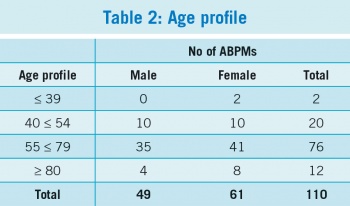

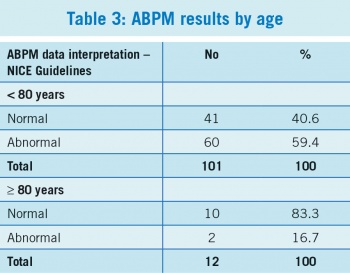

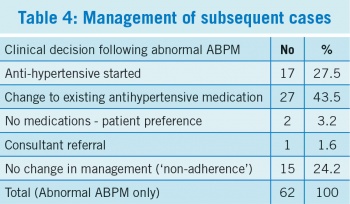

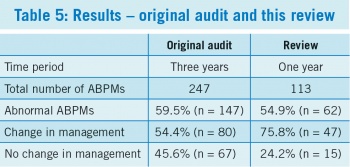

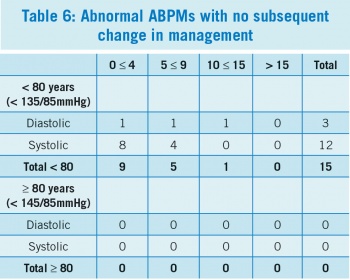

A total of 110 patients were included in the review with 113 ABPMs performed in total. We found that 54.9% (n = 62) of ABPM results were abnormal; patient management was subsequently changed in 75.8% (n = 47) of these. Thus, there was no change in management in 24.2% (n = 15) of abnormal cases. This represents a significant improvement over the original study, where 247 ABPMs were reviewed, 59.5% (n = 147) of results were abnormal, and no change in management was found in 45.6% (n = 67) of abnormal cases.3

Ambulatory blood pressure measurement

Ambulatory blood pressure measurement (ABPM) has become a cornerstone in clinical diagnosis and management of hypertension. We reviewed ABPM use in a large inner-city general practice in Dublin over a one-year period. Our aims were to identify improvements in adherence to NICE guidelines, following a previous study of practice ABPM use, and to identify reasons for non-adherence to guidelines, where this was the case.

Methods

We conducted an audit of patient records. The practice uses Meditech ABPM-04 hardware and Meditech software for 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and Socrates software for patient record management. We generated a report of all patients who had an ABPM carried out during the period November 1, 2013 to October 31, 2014. This included patient names and addresses, dates of birth, GMS eligibility, ABPM date and average daytime and night-time systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

We interpreted ABPM data using NICE guidelines and identified all abnormal results. We then reviewed patient electronic records and reviewed the clinical decisions taken in cases of abnormal ABPM results.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)