CHILD HEALTH

NUTRITION

WOMEN’S HEALTH

Promotion strategies to support breastfeeding

A number of barriers must be overcome to support Irish women, especially those with overweight and obesity, to breastfeed successfully

August 23, 2019

-

Breastfeeding provides the optimal nutrition for infants and children from birth to two years and beyond.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) endorses this position as do health services and governments globally.2 Breastfeeding also supports health in the woman and, as a result, the wider community.3

The associations for better maternal health relate to supporting the woman returning to her pre-pregnancy BMI, better pregnancy spacing, lower risk of breast cancer and diabetes later in life.3 The associations for the better infant health are decreased risk of SIDS, inner ear infections alongside lower long-term risk of developing obesity and type 2 diabetes.3 The wider felt community benefits are gained through increased presenteeism in parents due to improved health in their child and better longer term health in the mother.3 The cost of not breastfeeding is great, estimated at 0.7% and 0.42% of the global and EU gross national product respectively.4 In Ireland, this represents Ä1.6 billion per annum – not an inconsequential amount.

Irish breastfeeding rates are among the lowest worldwide.3, 5 This is not a statistic we should be proud of. In Ireland, only 60% of newborns receive any breastmilk, of which 50% are exclusively breastfed on discharge from the maternity services.6 This draws pale comparison to other developed countries such as Australia, where 96% are breastfed on discharge and exclusivity rates are 62% at four months.7 The rates of breastfeeding in Ireland have increased in recent years, but this is primarily being driven by women born overseas bringing their breastfeeding culture and practices to Ireland.6

Health promotion strategies are in place to support increased breastfeeding. The government is aware that this is an issue and the national action plan documents the need for a 2% year-on-year increase in breastfeeding if we are to make any progress on changing breastfeeding culture.2

Within the overall breastfeeding rates, some groups appear more vulnerable than others to not breastfeeding. These groups are women with diabetes in pregnancy,8,9 women with overweight or obesity10 and women from low socioeconomic backgrounds.11 In Ireland, breastfeeding rates are 32% for unemployed women compared with 66% in higher professional women.6 Women with type 1 diabetes and women with gestational diabetes are 62% and 25% less likely to breastfeed on discharge respectively.8 Finally, women with overweight or obesity are 13% less likely to initiate breastfeeding.10

If we apply this reduction to national statistics, it is a four to five women out of 10 breastfeeding compared with six out of ten across the population. While this difference may not be startling, when placed in the context that more than half of pregnant women have overweight or obesity, that difference is driving breastfeeding rates down, not up.

Knowing an issue exists and doing something about it are two very different things. There is plenty of evidence about what works in the general population. A Cochrane systematic review found that health professional-led education, non-health professional-led counselling and peer support interventions all work to increase breastfeeding initiation.12 Another Cochrane review found that interventions embedded into standard care, ongoing scheduled postpartum visits, interventions tailored to population needs, interventions delivered by health professional and peers, and face-to-face support all improved breastfeeding outcomes in the long-term.13

This work has informed interventions seeking to increase breastfeeding rates; the UCD Perinatal Research Centre in the National Maternity Hosptial and Wexford General Hospital recently piloted this multifaceted approach.14 Women on their first pregnancy received an antenatal group education class, a one-to-one lactation consultation after birth and access to a breastfeeding helpline, online resources and a breastfeeding support group which included a second one-to-one lactation consultation. The intervention found exclusive breastfeeding at three months was significantly increased (n = 32 of 45 Dublin, 71%; n = 9 of 15 Wexford, 60%)14 It also identified that mothers with raised BMIs were more at risk of not exclusively breastfeeding at three months15 and therefore were an at risk group to potentially target in a fully powered randomised trial.

Bearing this in mind, it is reasonable to assume that this style of intervention would be suitable for women with overweight and obesity. The reported barriers for Irish women are:

- Embarrassment and stigma about breastfeeding in public places and, in some cases, the home

- Perceptions that breastfeeding is inconvenient and requires extreme determination to succeed

- Lack of practical knowledge and experienced support.16

- Conversely, the enablers are:

- Seeing breastfeeding in the family and community

- Knowledge of breastfeeding benefits

- Practical and social support using a non-pressured approach.16

All of these enablers are aligned with international research, but there is a paucity of research in women with overweight and obesity, so we don’t know what the barriers and enablers are for this population sub-group and it may be that the pilot intervention is not suitable and a new approach is needed.

The UCD Perinatal Research Centre team designed a qualitative study to address this gap. The study used a interpretivist approach and included recorded interviews with a range of stakeholders from three different representative groups: women with raised BMIs who had successfully breastfed for more than six months (n= 20), partners of women who had successfully breastfed for more than six months (n = 20) and healthcare professionals who support women with overweight and obesity to breastfeed (n= 19).

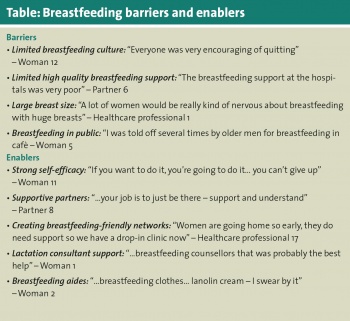

Several barriers and enablers were identified across the stakeholders (see Table).

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)