MENTAL HEALTH

GERIATRIC MEDICINE

Providing practical care for people with dementia

There are more than 40,000 dementia sufferers in Ireland, with 11 new cases diagnosed on a daily basis

February 1, 2013

-

The increased longevity of the world’s population or the greying of society should be celebrated as one of the greatest success stories of modern times. However, old age itself carries increased potential for many age-related chronic illnesses of which dementia one of the most feared.

Dementia in the Irish context

There are more than 40,000 dementia sufferers in Ireland, and with 11 new cases diagnosed on a daily basis, it is estimated that there will be 71,000 active cases by 2026.1 It is also estimated that 76% of the care of people with dementia (PWD) is by family members in the community or primary care. There are 50,000 family members looking after a loved one with dementia. When residential or nursing home care is examined, statistics have differed dramatically over the years. In 2007, the number of those in long-term care calculated to have dementia was 60-70%.2 This is a significant figure, although a more recent small study carried out by TCD researchers3 following mini mental (Folstein) testing in four nursing homes in south county Dublin found significant cognitive impairment in 89% of all residents assessed.

Primary care

From a primary care perspective, at the first national memory clinics conference in 2011, held in the Guinness Store House in Dublin, one memory clinic showed some very interesting findings in relation to individuals who were referred to the clinic for dementia.4 Of the 58 PWD who were seen over an 18-month period: five had depression, five had low B12/folate levels, and two were suffering from anxiety. This alone shows the importance of fully assessing anyone who may complain of memory problems as, in line with a delirium, there can be many causes of memory loss and confusion particularly in older people.

According to Prof Banarjee, the consultant psychiatrist who led the UK dementia management strategy, only one-third of PWD get a formal diagnosis, and when it happens it is often late into the illness – too late to enable choice, at a time of crisis, and too late to prevent harm and further crises. Prof Banarjee states that the cost of dementia in the UK is more than diabetes, cancer and heart disease put together. To date, the cost of dementia is not as fully researched in Ireland, but in 2006 it was estimated at E400 million with less than 10% attributed to community care.5

Testing domains

When someone presents with memory loss, confusion or a change in behaviour or mood it is wise to assess for mood disorder, rule out delirium and to conduct a dementia work up. Collateral history from a next of kin is vital, and if there is no next of kin, engaging with any others who have had access to the patient will be needed. The onset of the presenting complaint will help differentiate a delirium from dementia – although it may be the case that a delirium can superimpose a dementia. This is particularly significant in the acute hospital setting.

Delirium screening should look at ruling out any infective or medical cause of confusion and/or agitation. A full blood work up is needed with a particular focus on an infective screen, thyroid function, and if the patients is on any SSRIs, low sodium levels. Simple but very common causes of delirium in the elderly can be constipation, urinary tract infections and pain.

General testing

General testing domains in dementia are cognition, function, behaviour, and carer strain. Cognitive function includes performing a mini mental exam on the person, being mindful of their level of education with regards to the spelling of world and serial sevens. Usually, any score under 24 needs further investigation to uncover the underlying cause. The Geriatric Depression Scale should always be used with the mini mental exam because depression in the elderly can masquerade as dementia, causing them to score low on the mini mental exam.

Functional assessment can be carried out using different tools to assess their ADL independent abilities. Meanwhile, behavioural assessment can be very tricky: If a family member or relative has brought the person to your attention for behavioural issues, the illness may have progressed and a crisis, such as an aggressive or paranoid event, may have occurred. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) are discussed below.

Carer strain is a very important element in the primary care of someone with dementia. The carer’s support, knowledge and coping mechanisms for managing someone with dementia will dictate when the PWD enters long-term care. Working with family members and carers and arming them with the relevant skills and knowledge is required from very early on in the process.

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)

In 1995, the International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA) organised an international consensus conference on dementia and the associated behavioural issues.6 BPSD are categorised into two domains: behavioural and psychological. Behavioural symptoms include restlessness, physical aggression, screaming, agitation, wandering, sexual disinhibition, hoarding, cursing and shadowing. Psychological symptoms include anxiety, depression, hallucinations and delusions.

Understanding agitation

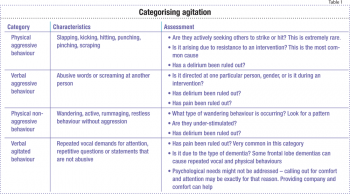

Some of the most common behavioural issues are that of agitation, wandering and aggression. In order to be able to assess, manage and treat agitation, it is of the utmost importance to investigate exactly what type of agitation is occurring and its description in detail. Agitation can be further categorised (see Table 1),7 so that when someone presents with BPSD and delirium has been ruled out from assessment, the exact type of agitation can be identified.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)