CARDIOLOGY AND VASCULAR

The ACS response time intervention trial

An individualised educational intervention has been shown to be effective in reducing pre-hospital delay time among patients who are readmitted with ACS symptoms

June 24, 2016

-

A multi-site parallel group randomised controlled clinical trial, entitled the ‘ACS Response Time Intervention Trial’1 tested the effect of an individualised educational intervention on patient pre-hospital delay time and behavioural responses to presumed symptoms of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Although time is of particular importance for those diagnosed with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), it is also important to rapidly diagnose the presence of non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina, not only to assign appropriate treatment but also to limit ischaemia.2,3

The time from ACS symptom onset until arrival at the emergency department (ED) is referred to as total pre-hospital delay time.4,5 Patient decision delay contributes most significantly to pre-hospital delay.6,7 Mass media campaigns have been predominantly used in an attempt to reduce patient pre-hospital delay time, the majority of which have been unsuccessful.8,9 In light of this, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) was developed to test whether an individualised educational intervention would be effective in reducing patient pre-hospital delay time in the presence of ACS symptoms.

Both groups received usual care from their healthcare provider, while those assigned to the intervention group also received the intervention. When a patient from either the control or intervention group was readmitted to an ED with ACS symptoms, data were again measured. In addition to pre-hospital delay time, the following reactions to symptoms were also measured:

- Time from symptom onset until the notification of another person that symptoms were present

- Whether the patient consulted a GP prior to attending the ED

- Whether prescribed nitrates were used

- Use of an ambulance as a mode of transport to the ED.

The primary and secondary hypotheses tested whether, on readmission to an ED, those assigned to the intervention group had reduced pre-hospital delay times and whether, in the presence of unresolved ACS symptoms, they conformed more readily to the recommended behaviours outlined in the intervention, compared to the control group. The study conformed to the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by each of the relevant institutional ethics committees.

Methods

The ACS Response Index10 was used to measure the primary and secondary trial outcomes. Group assignment was concealed until after baseline data were collected. Patients were randomised to the control or intervention groups according to their study numbers, which were allocated sequentially but group allocation was random.

The research nurse delivered a 30-40 minute education session to those assigned to the intervention group.

Sample

Patients were recruited from the coronary care units or cardiology wards across five tertiary Dublin hospitals and were generally enrolled to the study within two to four days of hospital admission. Clinical nurse managers and staff nurses acted as study gatekeepers. Study eligibility were: an ACS diagnosis (based on European Society of Cardiology Guidelines), being clinically stable at the time of enrolment, an ability to read, understand and communicate in English and access to a telephone.

Patients were excluded if they had any condition that prohibited them from understanding the intervention and/or decision-making process, such as a major or uncorrected hearing loss, a profound learning disability or any neurological disorder that impaired cognition. Those who lived in an institutional setting and those with serious complicating co-morbidities or untreated malignancies were also excluded from the trial.

Unlike previous research, patients were recruited with an ACS diagnosis and their pre-hospital delay times were measured on admission (baseline) and again on their first readmission to the ED with ACS symptoms.

The intervention

The educational intervention focused on pre-hospital delay time and the factors that influence it. The educational intervention was underpinned by Leventhal’s self-regulatory model of illness behaviour. This model advocates that the onset of symptoms triggers an individual to make behaviour adaptations. These adaptations occur in three stages, are processed both cognitively and emotionally, and are influenced by internal and environmental stimuli. Internal stimuli include sociodemographic factors such as age and gender. Environmental stimuli include messages from family or friends.

Using the intervention manual that was devised for the study, the education began with a simplified explanation about atherosclerosis and the mechanism by which a heart attack occurs. Participants were then gently but firmly reminded that their current ACS diagnosis rendered them more susceptible to a future ACS event than those without a history of ACS. The benefits of prompt hospitalisation in the presence of heart attack symptoms were highlighted, while the range and variability of symptoms were discussed in detail. Patients were made aware that the ‘Hollywood heart attack’ was only one of a range of manifestations of a heart attack or ACS symptoms. It was made clear that ACS symptoms are not individualised and that symptoms experienced on one occasion may differ on a subsequent occasion. They were instructed that the appropriate behaviour to take in the event of symptom occurrence was to stop and rest in the presence of symptoms, and if nitrates were prescribed, to use them. They should also inform another person about the symptoms and if symptoms persisted beyond 15 minutes, they were asked to call 999 or 112 for an ambulance without first summoning the advice of a GP.

In addressing emotional issues, advice was imparted about the role of emotions when ACS symptoms are present. It was acknowledged that emotional responses could interfere with symptom identification, acknowledgement and coping. The reasons for delay were discussed in the context of emotional responses. Participants were given pre-prepared scenarios to consider, as it was thought that the rehearsal of responses using role play would improve participants’ levels of perceived control on a subsequent occasion. The scenarios were selected to reflect each participant’s unique cardiac event experience. Participants were given a pre-printed wallet card with a summary of what to do in the presence of ACS symptoms. They also completed an action plan to take home as a reminder of what to do if symptoms recurred. The intervention was reinforced by telephone one month after the intervention was delivered and six months later, by post. Motivational interviewing techniques were used to promote the uptake of the intervention and to help participants reconcile elements of the intervention that they found challenging.

Results

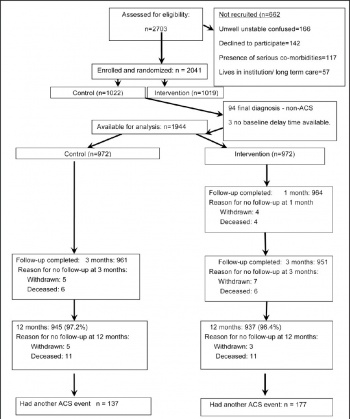

Of the 2,703 patients assessed for eligibility, 2,041 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled and randomised (Figure 1, CONSORT diagram). There were 1,944 patients with a definitive diagnosis of ACS and a documented pre-hospital delay time (Figure 1). Of these, 972 were randomised to the control group and 972 to the intervention group. A total of 24 patients withdrew from the study and 38 patients (2%) died. Of those who died, 17 (1.75%) were from the control group and 21 (2.2%) were from the intervention group. Median baseline pre-hospital delay time for the total sample was 4.04 hours (25th percentile 1.63 hours and 75th percentile 18.16 hours). There was no difference in pre-hospital delay time between the control (median 4.28 [25th percentile, 1.71 and 75th percentile, 17.37] and intervention median 3.96 [25th percentile, 1.53 and 75th percentile, 18.51]) (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.34) groups at baseline.

Sample cohort readmitted with ACS symptoms

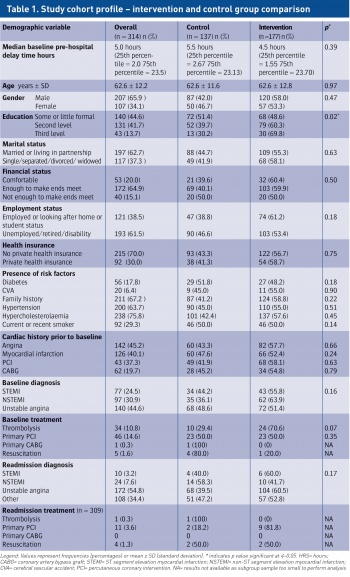

There were 314 (16.2%) patients readmitted to an ED with ACS symptoms. Of these, 137 (14.1%) were from the control group and 177 (18.2%) were from the intervention group (Figure 1). There was no significant difference between the two groups of patients who were readmitted with ACS symptoms with respect to baseline pre-hospital delay times (control median 5.5 hours [25th percentile, 2.67 and 75th percentile, 23.13] and intervention median 4.5 hours [25th percentile, 1.55 and 75th percentile, 23.70]) (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.39). The only significant difference between the two groups readmitted with ACS symptoms was the level of education attained (p = 0.02) (Table 1).

Impact of the educational intervention

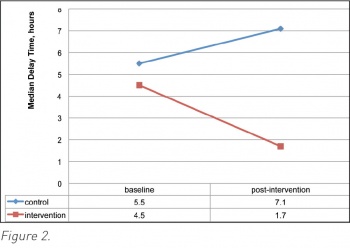

The two groups readmitted differed only with respect to education level (Table 1). Therefore, after controlling for education level, and using repeated measures ANOVA, we found that there was a significant post-intervention difference in pre-hospital delay times between the groups. Among the intervention group, the median pre-hospital delay time was reduced to 1.7 hours (25th percentile 1.1, 75th percentile 2.9) while the post-intervention median pre-hospital delay time for the control group readmitted increased to 7.1 hours (25th percentile 2.7, 75th percentile 16.7) (Figure 2). These post-intervention readmission pre-hospital delay times represent an increase of 1.6 hours in the control group and a reduction of 2.8 hours in the intervention group, with a difference of 5.4 hours between the groups. The change over time remained significantly different between the groups F (1,310) = 37.599, p = < 0.001. The primary study hypothesis was therefore accepted.

Impact of the intervention on pre-hospital behaviour

Using chi-square, we tested the impact of the intervention on the following behavioural responses to ACS symptoms:

Use of ambulance

Phoning or visiting a general practitioner for advice

Time to notification of someone else in response to symptom onset

Use of nitrate spray.

There was no significant difference in the use of ambulance (p = 0.51) or prescribed nitrates (p = 0.36) between the two groups. However, those assigned to the intervention group had a lower rate of consultation with a GP before attending the ED (p = 0.02). Furthermore, more people from the intervention group reported their symptoms to another individual within 30 minutes of onset (p = 0.01). The secondary hypothesis was not fully accepted.

Conclusion

This RCT was conducted over three years, comprised a large sample size and spanned five separate research sites. It was original in that baseline and post-intervention pre-hospital delay time data were collected and measured for the control and intervention groups. From a European perspective, this was the first RCT to target a reduction in patient pre-hospital delay time. Furthermore, it was the first reported RCT to be effective in this regard. This study should pave the way for change with respect to the content and delivery of usual pre-discharge education for patients with ACS.

Figure 1. Consort flow diagram(click to enlarge)

Figure 1. Consort flow diagram(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)