CHILD HEALTH

Therapeutic approaches to recurrent childhood headache

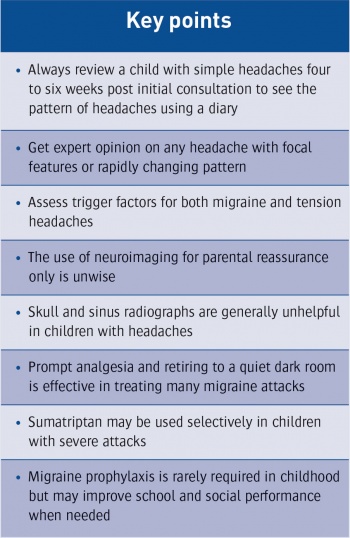

Childhood headaches can have many causes but it is always advisable to review a child with simple headaches four to six weeks after an initial consultation

October 5, 2015

-

Most recurrent headaches in children and adolescents are due to either migraine or tension headaches. As adult definitions of migraine do not always apply in children, there may be a continuum between migraine and tension headaches. In most cases potential underlying serious pathology can be ruled out by careful history taking and examination. Reassurance is very important and the doctor should concentrate on advice on lifestyle, the removal of possible trigger factors and simple analgesia. Investigations such as EEG and CT or MRI scanning are rarely indicated.

Points in the history

History taking is most important and both the child and the parent should be questioned to identify a number of important factors

Description of the headache episode

The physician requires a clear description of the nature of the headache, its localisation, its time course, its pattern (eg. diurnal variation, postural changes) and radiation (eg. to the eye) and if there are any associated features (aura, blurred vision, nausea, marked pallor, photophobia and vomiting).

Length of symptoms

The length of time the headaches have been present and any change in the severity and tempo of headaches are very important points in the history. Longstanding headaches that have not changed over the past 12 months are most unlikely to be associated with serious underlying pathology. In many respects a recent change or increase in the tempo or severity of headaches is the most important aspect of the history and should always arouse concern.

Timing of the headache

Ask whether the headaches tend to be in the evening or in early morning, just on school days or at weekends, and enquire as to how long they last.

School days lost

It is very important to know how much time off school the child has had due to headaches and how academic progress has been thereby affected, if at all. If many school days are being missed a report from the class teacher and enquiry into general progress and happiness at school is required. Ask also about the length of time spent on homework and the number of extracurricular activities taken by the child.

Precipitants of headaches

It may or may not be clear from the history whether particular foods, light, stress or intense exercise bring on headaches. Enquire also what the child does to relieve the headaches, how quickly they tend to take analgesics and whether they need to lie down to relieve the headache.

Remedies tried

Explore what remedies have been tried by the parents including use of analgesia, dietary changes, home remedies and preventive medications.

Family history

Ask about a family history of migraine, travel-sickness, vertigo and epilepsy.

Important examination findings

All children with headaches should have a complete physical examination concentrating on:

Measurement of head circumference (watch for macrocephaly)

Height and weight centiles (short stature in craniopharyngioma)

BP measurement (may be elevated if raised intracranial pressure)

Assessment for neuro-cutaneous stigmata (eg. café-au-lait spots of neurofibromatosis type 1)

Full cranial nerve assessment including extraocular movements, fundoscopy, looking for loss of venous pulsation, papilloedema, and optic atrophy

Assessment of visual acuity and visual fields

Look for head tilt (may be a presenting feature of a posterior fossa tumour)

Gait analysis (ataxia may be a feature of posterior fossa tumour).

Migraine and its variants

Migraine affects 3-10% of children and 20% may experience their first attack prior to five years of age. Incidence increases steadily with age, affecting boys and girls equally before puberty and girls more commonly thereafter.1,2,3

Migraine is characterised by episodes of head pain that is always throbbing and frequently unilateral frontal or temporal in position. Pallor is a prominent feature and the child may be described as being ‘ghostly pale’. Most children with significant migraine stop what they are doing and go to a darkened room, lie down and fall asleep. The headache is often gone on awakening. Headache due to migraine lasts more than three hours and less than 72 hours (status migranosus is greater than 72 hours in duration and needs emergency management).

Acute migraine is of relatively sudden onset, and can occur with or without a prodrome, also known as aura. In migraine without aura (or common migraine), attacks are associated with nausea, vomiting, or sensitivity to light sound or movement.

Up to 15% of patients suffer from migraine with aura (or classic migraine); in such patients migraine is preceded by transient focal neurologic symptoms, which are commonly visual (eg. scotoma, fortification spectra) and resolve with the onset of head pain. Derealisation phenomena such as macropsia-micropsia are experienced by some children, also known as ‘Alice in Wonderland syndrome’.4,5

Triggers

Triggers for migraine include stress, fasting, sleep deprivation and extremes of activity. Food triggers may sometimes be identified and it may be useful to keep a record of what is eaten just prior to a headache to see if a consistent pattern emerges. Common culprits include nuts, caffeine (including cola drinks), citrus fruits, spiced meats, monosodium glutamate, chocolate and blue cheese.6 Exercise, especially if associated with competitive sports, may precipitate migraine in some children. Oestrogens and androgens are likely to be responsible for the change in the incidence of migraine seen at or around puberty.

Treatment

Treatment in paediatric migraine includes an individually tailored regimen of both non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic measurements.

Non-pharmacologic modalities include lifestyle adjustments, thus regular sleep, regular meals, exercise, avoidance of peaks of stress and dietary triggers. Parents should be encouraged to keep a headache diary as this may indicate such factors as well as the frequency of episodes. Once parents are familiar with their child’s pattern of migraine they should be encouraged to treat with analgesics as early as possible. In fact, analgesia and rest in a quiet room, if initiated at the very first sign of headache, may be effective in aborting the episode.

Most children with migraine can be treated with simple analgesics such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Other symptomatic medications include the following.

Triptans

For example, sumatriptan and frovatriptan, are selective agonist of 5-hydroxytryptamine; three randomised controlled trials have demonstrated that nasal sumatriptan is both safe and effective in adolescents with a severe attack of migraine. It can also be administered orally and by subcutaneous injection. Drowsiness is a recognised common side effect. Disadvantages include high cost and contraindication in cardiovascular patients

Calcium channel blockers

For example, buclizine and flunarizine, are of proven benefit and relatively safe. Side effects include low blood pressure and tiredness

Opiates

As a rule opiates should be avoided because they seem to mask the pain without suppressing the pathophysiologic mechanism of the attack, often leading to addiction.

Ergot alkaloids

For example, methysergide, are very potent, but should be avoided in children under 12 years due to the possibility of vasospasm and should be administered only by specialists.

Anti-emetics

Domperidone and metaclopramide, and clonidine, have all been found to have some beneficial effect in small placebo controlled studies, but were not shown to reduce headache frequency or duration.

Herbal remedies

Things like feverfew, an easily grown daisy-like plant, have been shown to be effective in migraine treatment in adults.

Preventive therapy

If a child is getting very frequent migraine headaches (eg. more than two attacks a month) and thereby missing days of school, prophylaxis is indicated. Preventive therapy should also be considered if the patient is at risk of rebound headache or if the frequency and severity of attacks is increasing. The available options are the following:8,9,10

Beta-adrenergic-receptor antagonists – for example propranolol and metoprolol – there is a paucity of studies showing a beneficial effect, and in some patients they could potentially worsen symptoms; they should be avoided in patients with asthma

Calcium channel blockers (eg. buclazine, flunarizine)

Pizotifen has also been evaluated and, in two clinical trials, both had significant methodological flaws that considerably limited the interpretation of their results; side effects include drowsiness and weight gain

Amitriptyline (tricyclic antidepressant) used at a low dose at bed time has a proven benefit in adult patients; side effects include drowsiness

Topiramate (a new generation anti-epileptic agent) is a promising agent yet not fully studied in migraine; side effects include weight loss and confusion.

Migraine variants

When the neurological symptoms and signs associated with migraine appear after the headache onset (eg. Horner’s syndrome, hemifield deficits), this is referred to as transformation migraine12

In ophthalmoplegic migraine there is often ptosis and a divergent squint and occasionally this may last for more than 24 hours

Hemiplegic migraine is rare and often familial and the hemiplegia may outlast the headache, but rarely lasts more than six to 12 hours

Basilar migraine is characterised by dizziness and vertigo as predominant features; it is relatively short-lived and very occasionally there may be an associated bilateral transient visual loss.

Outcome of childhood migraine

There are very few long-term studies, but it appears that the outcome seems to be better in boys than in girls. Outcome seems to be worse if headaches start before the age of six years. Many children with migraine will follow family patterns and thus genetic factors appear important. Migraine does tend to decrease in frequency and severity with age, but this may not occur until early middle-age has been reached.

Tension headaches

Tension headaches are the other main cause of headache in childhood. Typically they are a response to stress. Tension headaches have a number of characteristics in that they tend to be bilateral, they vary in severity and have a pressing or tightening quality. Scalp pain needs to be elicited in the history, suggested by pain on brushing hair etc. The triggers for tension headaches may include school bullying, excessive extracurricular activities after school, marital discord, unemployment, death in the family or moving home. Suggested strategies to reduce tension headaches include:

Looking for and correcting the cause of stress

Avoiding frequent analgesia if possible

Encourage normal school attendance

Clearly explain the non-serious nature of tension headaches to the child

Relaxation exercises, physiotherapy and hypnosis may be helpful.

Differential diagnosis

Brain tumours

Although much feared, brain tumours are relatively infrequent occurrences in childhood with an incidence of three per 100,000. Children with brain tumours usually have symptoms other than headache only.7

Infratentorial tumours may present in the absence of headache, with difficulty in walking, confusion, hyperreflexia, cranial nerve palsies and head tilt. Supratentorial tumours presenting with a headache may also have diplopia, poor academic performance, seizures, focal hyperaesthesia of a limb or speech impairment.

It is traditionally understood that the headache of raised intracranial pressure awakens the child from sleep, is maximal in the morning and improves during the day. While such a history should always trigger concern, the lack of this pattern does not exclude raised intracranial pressure.

As stated above, an increased tempo and severity of headaches is most important and should arouse concern regarding the possibility of serious brain pathology. Children with brain tumours may present with a story of initial mild headaches increasing in a crescendo fashion to severe and frequent headaches. The reverse is also true in that headaches recurring over a period longer than six months in the absence of other neurological symptoms are rarely due to a brain tumour.

The one exception to this rule is a craniopharyngioma, in which there are usually other clues such as short stature, delayed puberty and visual field defects.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is the clinical syndrome of raised intracranial pressure, in the absence of space-occupying lesions or vascular lesions, without enlargement of the cerebral ventricles, for which no causative factor can be identified.13

It was previously known as benign intracranial hypertension, however, it is now recognised as a malignant phenomenon. It can rapidly lead to irreversible blindness. This may present with a severe frontal headache that interferes with normal daily activities. The headache may increase in intensity on bending over and is often more frequent in the morning. The patient may also complain of intermittent darkening of parts or the whole of their visual fields (transient visual obscuration). Neurological examination is abnormal including papilloedema and optic atrophy on fundoscopy, and at times a sixth nerve palsy. Neuroimaging is normal.

Diagnosis is based on history, exam and lumbar puncture with high opening pressure and formal visual field assessment. Associated factors are obesity, steroids withdrawal, hormonal contraceptive use, some antimicrobial agents, vitamin A, and also venous sinus stenosis.

Prompt referral to a tertiary centre is warranted. Treatment options include carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, loop diuretics, fenestration of the optic nerve, high volume lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunting.

Sinusitis

Ethmoid and frontal sinusitis may be associated with headache in older children. The headache is usually throbbing, dull and made worse when the child bends over or coughs. Percussion of the sinuses may elicit tenderness. Sinus radiographs and ENT referral may be organised.

Hydrocephalus and shunt blockage

In those children with known hydrocephalus who have a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt in-situ, shunt malfunction (mechanical or infection) needs to be considered especially if headaches are associated with vomiting, altered consciousness or signs of raised intracranial pressure.

Neuroimaging

In a previously healthy child with headache, criteria for requesting neuroimaging include:

An accompanying change in personality

Abnormal neurological or visual examination

Frequent or persistent vomiting

Crescendo pattern of headaches

Signs of raised intracranial pressure

Focal and generalised seizures.

Up to 30% of CT/MRI brain scans performed are for parental reassurance and, apart from resource and radiation exposure implications, it is important to stress to parents that early investigation and the finding of a normal CT/MRI scan may give a false sense of reassurance and potentially delay rescanning if the headache characteristics change.

Careful history taking and examination and follow-up with a headache diary is the key to the proper evaluation of headaches rather than resorting to neuroimaging.

It is important to stress to parents that CT brain scans are equivalent in radiation exposure to some 80 chest x-rays and therefore CT should not be performed for reassurance only.11