CHILD HEALTH

MENTAL HEALTH

NEUROLOGY

MEN'S HEALTH I

Adrenoleukodystrophy in a young child

A case of the rare neurological condition, adrenoleukodystrophy, in a young patient

October 1, 2013

-

A six-year-old male presented to the emergency department (ED) with an eight-week history of clumsiness, falls, behavioural changes and global developmental regression. On examination he was alert and orientated but with poor attention and single-word answers. Neurological examination revealed subtle abnormalities. Subsequent neuroimaging and plasma very long-chain fatty acid (VLCFA) levels confirmed the diagnosis of adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD).

Background

ALD is a rare presentation of neurological deficit with an incidence ranging between 1/20,000-1/100,000.1 Time between onset and diagnosis is also delayed, particularly in probands.2

Case presentation

A six-year-old male patient of sallow complexion presented to the ED with an eight-week history of global developmental regression. His mother first noticed the patient having staring episodes which slowly progressed to declining content and character of speech, behavioural changes and attention deficit. There was also a history of urinary incontinence.

Neurological examination proved unremarkable with the exception of an unsteady gait, positive heel to toe walking and past pointing. Birth history was unremarkable; the patient was born at 39 weeks by elective Caesarean section as one male of dizygous male twins. His neonatal period and developmental milestones were completely normal.

With regard to family history, the mother reported that two of her father’s siblings died of motor neuron disease (MND), one female at 54 years old and one male at 69 years old.

Investigations

Audiology and visual assessment tests performed prior to admission were normal. Biochemical and haematological investigations were unremarkable.

Electroencephalography (EEG) revealed abnormal photoparoxysmal response to intermittent flash stimulation during waking and drowsy states only, though this was not associated with any clinical changes.

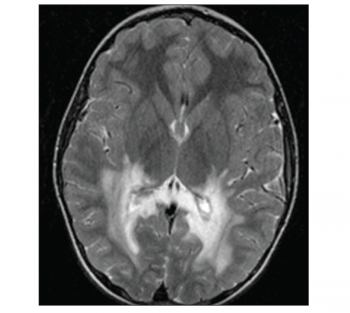

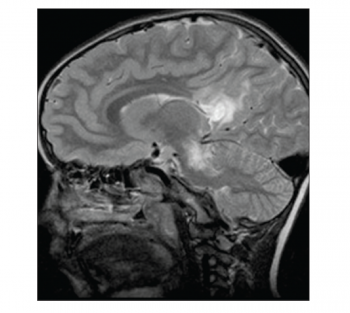

The remainder of the waking record showed no definite epileptiform features. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated extensive diffuse deep white matter high signal change extending inferiorly along the white matter tracts as far as the superior aspect of the pons and brain stem on axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and axial T2-weighted sequences.

Extensive high signal changes were seen in the posterior corpus callosum. These extensive changes were bilateral and symmetrical showing moderate peripheral rim enhancement post-gadolinium administration.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test was performed and confirmed adrenal insufficiency with cortisol level at 0 minutes: 282, at 30 minutes: 284 and at 60 minutes: 289.

Differential diagnosis

Early behavioural changes are described in 13% of patients diagnosed with ALD and hyperactivity in 6% often leading to the diagnosis of hyperactivity or attention deficit disorders in the early stage of the disease.3

Seizures are the presenting complaint in 7% of ALD patients often leading to the suspicion of epilepsy.1 In the later stages, the disease emulates encephalitis and brain tumours, other neurodegenerative disorders such as arylsulfatase deficiency (metachromatic leukodystrophy) and Krabbe disease (globoid cell leukodystrophy); subacute sclerosing encephalitis, multiple sclerosis, Lyme disease, and other dementing disorders including juvenile neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis (Batten disease) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Brain MRI studies and plasma VLCFA assay will lead to definitive diagnosis.4

Treatment

A definitive cure does not yet exist for ALD but three treatment options significantly improve prognosis if initiated in the early stage of the disease.

Dietary treatment with Lorenzo’s oil was shown to decrease plasma VLCFAs to undetectable levels at four weeks post-therapy but so far has been unsuccessful in preventing progression in neurologically symptomatic patients. However, asymptomatic patients may still benefit. Haematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) have proven therapeutic benefit in patients with mild cerebral impairment, where a suitable donor can be found.2

The third treatment option, adrenal replacement therapy, which was initiated in this case with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone, prevents life-threatening adrenal events but has not been shown to slow neurological progression.5

Figure 1. Axial T-weighted image showing bilateral extensive white matter lesion in the occipital lobe(click to enlarge)

Figure 1. Axial T-weighted image showing bilateral extensive white matter lesion in the occipital lobe(click to enlarge)

Figure 2. Sagittal T2-MRI image showing extensive white matter lesions affecting posterior lobe, pons and midbrain(click to enlarge)

Figure 2. Sagittal T2-MRI image showing extensive white matter lesions affecting posterior lobe, pons and midbrain(click to enlarge)