NEUROLOGY

Management of head injury

Focus on the management of head injuries

November 4, 2016

-

This clinical update on head injuries includes initial assessment and examination of people presenting with head injury. It also explains the concepts of ‘red flags’ and potential complications of head injuries.

Head injury is defined as any trauma to the head other than superficial injuries to the face.1 Most head injuries are caused by falls, sports-related incidents and motor vehicle collisions. Approximately 10,000 new head injuries occur in Ireland each year.2

The majority of people who attend emergency departments with head injury will have a minor injury, although approximately 20% of these will be admitted to hospital.3 The majority of people with a minor head injury will recover without specific or specialist intervention.1

However, trauma is the leading cause of death in people under the age of 45 years, and up to 50% of these deaths are as a result of a head injury.3 The majority of deaths from head injury are in people who present with a moderately or severely impaired consciousness level.1

Assessment

The assessment of a person with a head injury consists of taking a history and an examination, including a Glasgow Coma Scale score. When assessing a person who has a head injury you should ask how and when the head injury occurred. If possible you should ask about recent alcohol or drug intake, current anticoagulant medication, pre-injury level of consciousness and functioning.1,3 People who have dementia, for example, may have different levels of pre-injury cognitive functioning to those without dementia.

It is important to note that people who present with loss of consciousness, amnesia, vomiting, headache or neck pain are more likely to have a serious head injury. The following circumstances are more likely to cause serious head injury:

• Falls from a height of greater than one metre or five stairs

• High-speed motor vehicle collisions, either as a pedestrian, cyclist or vehicle occupant

• Rollover motor accidents or ejection from a motor vehicle

• Accidents involving motorised recreational vehicles or bicycle collision

• Diving accidents.

In children you should consider the possibility of non-accidental injury if:

• The child is not yet independently mobile (crawling, cruising, walking)

• The bruise is on any non-bony part of the face (including eyes or ears)

• The injury is to both sides of the face or head

• The bruises are at variance to the explanation given by the parents or carers

• Retinal haemorrhages or injury to the eye (in the absence of major confirmed accidental trauma or a known medical explanation) should also be considered a ‘red flag’ for non-accidental injury.5

Examination

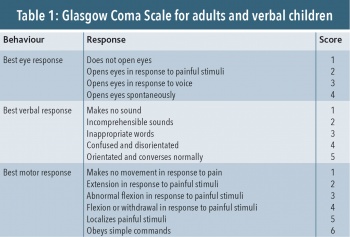

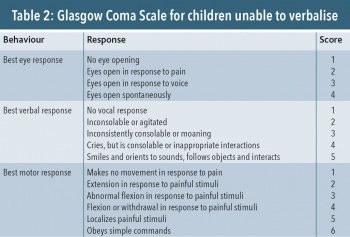

Examine the person to assess their level of consciousness, using the Glasgow Coma Score (see Tables 1 and 2). Look for signs of breathing difficulties or shock such as increased heart rate, low blood pressure or reduced capillary refill time.

Examine the patient for signs of visible trauma to the scalp, skull, head and neck. Check pupil size and that pupils are reacting normally to light. Look for any problems with vision or speech disturbance, understanding speech, reading or writing.

If the person has been standing check for any problems with balance or walking. Ask about and test for any numbness in the upper or lower limbs. Test reflexes and look for any loss of muscle power. If appropriate, assess the person’s neck for tenderness and movement ability. Safe examination of the neck should only be performed if the person was not involved in a high-energy injury, is comfortable in a sitting position, has been walking at any time since the injury, has no tenderness along the spine, or describes a problem with delayed onset neck pain.

Signs of very serious injury include:

• Clear fluid (possible cerebrospinal fluid) leaking from the ear(s) or nose

• Bruising around the eyes (with no associated damage around the eyes)

• Bleeding from one or both ears

• Blood behind the ear drum

• New deafness in one or both ears

• Bruising behind one or both ears.1

Glasgow Coma Scale

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)3 is used internationally in clinical practice to assess the depth and duration of impaired consciousness and coma.

It is used to assess the level of consciousness in all people who have received a head injury (including people who appear intoxicated). People are scored on three different aspects of behavioural response: eye opening, verbal and motor responses. Each area of assessment is evaluated independently of the other and graded, with the lowest possible score being 3 (deep coma or death) and the highest being 15 (fully awake).

For example, a person with a best score of 4 for eye response, 5 for verbal response, and 5 for motor response should be recorded as E4, V5, M5 and the total score of 14/15 given.

People with dementia, chronic neurological disorders or learning difficulties may have a pre-injury baseline GCS score of <15, which should be taken into account during clinical assessment.

The Glasgow Coma Scale score can be translated into severity of the head injury:

• Mild – score of 13-15

• Moderate – score of 9-12

• Severe – score of 8 or less.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)