MENTAL HEALTH

Psychosis associated with prolactin-secreting pituitary macroadenoma

Treating and diagnosing patients with both psychosis and a pituitary adenoma presents a unique challenge for clinicians

March 1, 2012

-

A pituitary adenoma is prolactin-secreting tumour and is classified based on its size as a microprolactinoma (< 10mm diameter) or a macroprolactinoma (> 10mm diameter).1,4 Dopamine is the principal prolactin-inhibitory factor; hence dopamine agonists reduce the prolactin level and often will shrink a prolactin-secreting pituitary adenoma. Studies have confirmed that typical and atypical antipsychotics act as dopamine receptor blockers and consequently increase the prolactin level.8,9

Recent studies revealed aripiprazole, which is a partial dopamine agonist, has little or no effect on the prolactin level.8,12 These findings have various implications in diagnosing and managing patients with a prolactinoma, psychosis or combination of both conditions. Around 60% of male patients with prolactinomas have macroprolactinomas, and 90% of female counterparts present with microprolactinomas.4,11 This is likely because the presenting symptom for male patients is typically hypogonadism while female patients present with amenorrhoea, which will be evident much sooner.4,11 Pituitary macroadenoma space-occupying neurological symptoms are generally headaches and visual problems in the form of field defects.

The visual problems range from compression of the optic chiasm, causing bitemporal hemianopsia, to the compression of cranial nerves III, IV or VI causing ophthalmoplegia.4 Neuroimaging, especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is sensitive in diagnosing pituitary macroadenoma. However, since less than 3% of institutionalised psychiatric patients have intracranial tumours, debates remain between psychiatrists and neurologists about whether all patients with new-onset psychiatric symptoms should undergo routine neuroimaging.5

Case report

AZ is a 28-year-old, married, employed, Caucasian male who presents with new-onset psychosis. He suddenly quit his job and engaged in various uncompleted new projects. He denied any history of drug or alcohol abuse and had no significant family history of mental illness, except two uncles with alcohol-related disorders. His only medical history was a motor vehicle accident nine years prior; he was unconscious for few seconds but recovered without any sequelae.

He reported a two-year history of frontal headaches and a few months of low mood, insomnia, anhedonia, anorexia, anergia, intermittent confusion and poor concentration. On examination he was irritable, perplexed, with disorganised thoughts and pessimism about the future with suicidal thoughts but no specific plan. He had racing thoughts that were tangential and circumstantial, pressured speech, flight of ideas and a labile affect. He also had paranoid/persecutory delusions with second- and third-person auditory hallucinations with the voices running commentary on his actions. Collateral information from wife and sister confirmed bizarre behaviour for two weeks.

Once admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit he was started on risperidone and escitalopram, and his symptoms improved significantly, however he developed galactorrhoea and a severe headache after three weeks on these medications. An endocrinologist was consulted due to elevated prolactin 21.57 ng/ml (normal level: 2.1-17.7 ng/ml). The hyperprolactinaemia was attributed to the risperidone, which was subsequently discontinued. AZ was then started on aripiprazole and his prolactin level normalised to 0.71 ng/ml, exactly three months after initial level of 21.57 ng/ml.

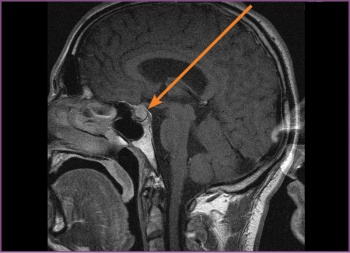

However, despite AZ’s normalised prolactin, his headaches persisted, hence an MRI of the brain, T1-weighted, was ordered. The MRI revealed a macroadenoma in the pituitary fossa, which extended into the suprasellar region compressing the chiasma, there was also dilatation of the third and lateral ventricles suggesting some degree of compression at the aqua duct (see Figure 1). AZ was discharged from the psychiatric unit on aripiprazole to follow up with the endocrinologist, who prescribed cabergoline 0.25mg twice weekly.

Figure 1: Pre-surgery, the first MRI, T1-weighted (sagittal) – the pituitary fossa shows a macroadenoma (11 mm)(click to enlarge)

Figure 1: Pre-surgery, the first MRI, T1-weighted (sagittal) – the pituitary fossa shows a macroadenoma (11 mm)(click to enlarge)

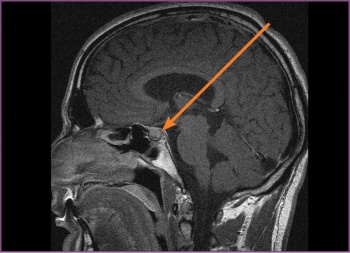

Figure 2: Second MRI T1-weighted (sagittal) – the pituitary fossa shows a macroadenoma. Pre-surgery, almost one year on cabergoline and no significant changes in the size of the macroadenoma(click to enlarge)

Figure 2: Second MRI T1-weighted (sagittal) – the pituitary fossa shows a macroadenoma. Pre-surgery, almost one year on cabergoline and no significant changes in the size of the macroadenoma(click to enlarge)