ENDOCRINOLOGY

Severe dyslipidaemia in asymptomatic patient

An outline of the diagnosis and management of severe dyslipidaemia in an asymptomatic patient

September 1, 2015

-

A 35-year-old male attended an acute medical assessment unit (AMAU) complaining of polyuria, polydipsia for two weeks. He had no past medical history of note and was not on any regular medications. His father was diagnosed with diabetes at the age of 65 and had a history of hypertension. The patient is a non-smoker and does not drink alcohol.

On initial presentation his blood pressure was 156/99 and on recheck was 130/90. He has a high BMI of 33.97kg/m2 (weight 115kg, height 1.84m, waist circumference 1.30m). Otherwise his physical examination was unremarkable with no evidence of xanthoma or xanthelasma. His glucose reading on presentation was 15.1mmol/mol with ketone of 0.9mmol/L. pH on VBG was 7.315 with a HCO3- of 24.2mEq/L. CRP was 10mg/L (0 to 5) with Wcc of 11.6 x 10 ̂9/L (4 to 10). His chest x-ray was reported as normal. He was started on diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) protocol when he was in the AMAU. His repeat gas showed a pH of 7.354, HCO3- of 21mEq/L. He was started on metformin and glicazide MR. He was also reviewed by the dietitian and diabetes nurse specialist.

Interestingly, his cholesterol came back at 20.65mmol/L, triglyceride >64.2mmol/L and LDL 0.54mmol/L. His amylase level was normal at 38Iu/L (25 to 105). Retrospectively, on questioning the patient, there was no family history of sudden death, premature ischaemic heart disease or pancreatitis. His other bloods results include AntiGAD 3U/ml (0 to 10), HbA1c 105mmol/mol (11.8%), liver blood test normal and thyroid function test normal.

He was started on insulin infusion at initial rate of six units per hour which was then titrated up to 10 units per hour over a four days period. He was initially commenced on rosuvastatin when he was in AMAU after which, this was switched to gemfibrozil (Lopid) 600mg bd. His cholesterol was 7.14mmol/L, triglyceride 11.17mmol/L, and LDL 2.16mmol/L on discharge.

Diagnosis made on discharge was new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus (type 2 DM), secondary dyslipidaemia and metabolic syndrome (syndrome X).

He was followed up in the outpatients department five months later. Unfortunately he had gained weight in the interim. His weight in OPD was 126.2kg, compared to 115kg on admission. His BP was 150/70, urine dipstick showed a raised albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR). His cholesterol was 5.37mmol/L with triglyceride of 3.60mmol/mol. His HbA1C was 52mmol/mol (6.9%), which did show improvement from the previous reading of 105mmol/mol (11.8%).

His glycaemic control was still suboptimal. We added a GLP-1 agonist liraglutide (Victoza) to improve his glycaemic control. We added ramipril 2.5mg to his medication regime and requested a 24-hour urinary protein and 24-hour blood pressure monitor for him. The 24-hour urinary protein was 651mg/24hr (20 to 300). We also booked an ultrasound renal for him and the report came back as unremarkable. We emphasised the importance to lose weight at the first instance in light of the known comorbidities. We referred him to the lipid clinic at St James’s Hospital, Dublin for further follow up.

Discussion

Dyslipidaemia is a major risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Severe hypertriglyceridaemia increases risk of pancreatitis. Features of diabetic dyslipidaemia include:

- Plasma triglyceride concentration

- LDL

- HDL cholesterol.

These lipid changes are attributed to an increase in free fatty acid flux secondary to insulin resistance.1 The prevalence of severe hypertriglyceridaemia (triglycerides ≥ 2,000mg/dL) is 1.8 cases per 10,000. The prevalence of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) deficiency in patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia is approximately one case in one million. The prevalence of apolipoprotein C-II deficiency is lower compared to LPL deficiency. Prevalence of hypertriglyceridaemia is lower in African Americans than in whites.

Mild hypertriglyceridaemia (>200mg/dL) are more prevalent in male (approximately 18%) compared to female (4.2%). Triglyceride levels tend to increase in men until about 50 years of age and then may decline slightly, whereas females have a continuous increase with age. (LPL) and apoC-II deficiency are usually diagnosed in childhood. In the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS, 1997), females with type 2 DM had a markedly raised LDL compared with the non-diabetic women population. It also showed that plasma triglyceride level was high in patients with type 2 DM. HDL were markedly low in both diabetic gender compared to non-diabetics.2

According to WHO, about 230 million people have from type 2 DM worldwide, which is estimated to rise to 400 million by 2025. Around 40% of type 2 DM patients have dyslipidaemia, including hypertriglyceridaemia. About 19% of patients who have both hyperglycaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia suffer from coronary disease.

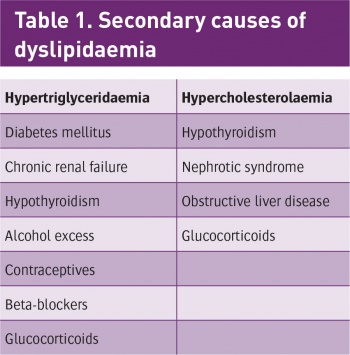

Hyperlipidaemia can be classified either as primary or secondary, according to the types of lipids being elevated. Primary hyperlipidaemia (familial) is usually due to genetic causes (such as a mutation in a receptor protein). Secondary hyperlipidaemia arises due to other underlying causes such as diabetes (see Table 1).

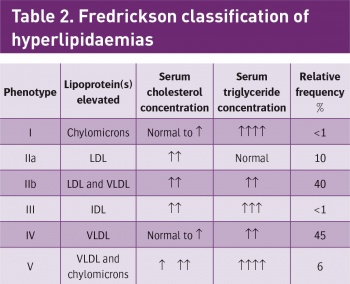

Hyperlipidaemias are also classified according to which types of lipids are elevated. This classification is according to the Fredrickson classification which is based on the pattern of lipoproteins on electrophoresis or ultracentrifugation (see Table 2).

Treatment for dyslipidaemia includes lifestyle changes (exercise, weight loss, dietary modification) and pharmacologic interventions. For diabetic dyslipidaemia, statins are the drug of choice. In patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia, especially triglyceride levels greater than 1,000mg/dL (11.29mmol/L), fibrate therapy and/or niacin and fish oil should be used. Intravenous insulin may be considered as another therapeutic option for hospitalised individuals.3

In addition to statins, interventional trials have shown that fibrates and nicotinic acid have therapeutic roles in prevention of cardiovascular disease related events.4,5 Treatment with gemfibrozil is associated with 22% reduction in CHD and 25% reduction in risk of stroke.6

It is important to remember drug interactions and side effects with lipid-lowering medications. The combination of statin and fibrate or nicotinic acid increases the risk of rhabdomyolysis. The use of macrolide antibiotics on patients taking statins will increase the risk of muscle toxicity. Hence, statins should be held while patients are on macrolide antibiotic. Bloating and constipation are potential side effects with bile acid sequestrants.

There are several studies that mention the use of intravenous insulin infusion to treat severe hypertriglyceridaemia as in our case report. The administration of continuous insulin in patients with type 2 DM with severe hypertriglyceridaemia is a simple and safe method of significantly reducing the immediate risk associated with this metabolic complication and should be considered in any type 2 DM patient presenting with severe hypertriglyceridaemia and hyperglycaemia.7

There was another study where patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia (triglyceride levels >1,000mg/dL) were treated with insulin therapy. Two and a half days after treatment, the serum triglyceride level remained lower than 400mg/dL. The conclusion of the study was insulin therapy for diabetic and non-diabetic patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia is an effective and safe treatment.8

- Metabolic syndrome (syndrome X) is diagnosed when there are three or more of the criteria below present:

- Raised fasting glucose

- Hypertension

- Low serum HDL

- Elevated serum triglyceride

- Abdominal obesity.

In conclusion, aggressive therapy of diabetic dyslipidaemia will reduce the risk of CHD in patients with diabetes. This includes a combination of lifestyle modification and pharmacological approach. The use of continuous intravenous insulin has been shown to be effective in some published studies to treat severe dyslipidaemia. Other risk factors such as hypertension, obesity and hyperglycaemia must be effectively managed concomitantly.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)