MENTAL HEALTH

The link between depression and diabetes – current research

A review of current research on the link between depressive disorders and diabetes, and why there are still unanswered questions about the causes, consequences and methods of management

March 16, 2016

-

Depression is highly prevalent worldwide, being associated with significant mortality and morbidity. According to WHO estimates, it is responsible for the greatest proportion of burden associated with non-fatal health outcomes and accounts for 12% of total years lived with disability.1 Major depression is the second leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost in women and the 10th leading cause of DALYs in men.2

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic debilitating disease with the highest mortality rates in countries with large populations such as China, India, the US and Russia.3 It is a highly prevalent disease that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality worldwide.

There is an appreciable interest in the psychological wellbeing of people with diabetes. Those with depressive disorders have an increased risk of developing diabetes.4 Despite the huge impact of the co-existence of depression and diabetes on an individual and its enormous importance as a public health problem, there are unanswered questions about the nature of the link, causes, consequences and possible ways of management of these two conditions.

Epidemiology of depression and diabetes

In people with diabetes, the prevalence of clinically relevant depressive disorders is up to one third.5,6,7 The prognosis of both diabetes and depression is worse when the two diseases are comorbid than when they occur separately.8,9 Rates of depression are particularly high in patients with type 2 diabetes with less evidence for type 1.7 There are regional and cultural differences in prevalence of comorbid depression with diabetes. Studies have suggested that levels of comorbid depression are higher in Hispanics than in people of African origin, which in turn are higher than in Caucasians.10,11,12,13,14

There is a variation in the prevalence rates of depression across Europe but it is consistently higher in people with diabetes compared to those without.15,16 Possible confounding factors in this variation may be a reflection of socioeconomic, environmental and cultural differences and variation in assessment methods. Clearly there may well be international variations in the rates of comorbid depression and diabetes, however these need to be clarified in future studies, with improved methodology to measure these variations. The frequency of recurrence and duration of episodes of depression tend to be higher in patients with diabetes.17,18,19

The risk factors for depression in diabetes20,21 can be divided into two:

Non-diabetes specific risk factors, including female gender, lack of social supports, low socioeconomic status and critical life events

Diabetes specific risk factors, including poor glycaemic control, late complications of diabetes, need for insulin in type 2 and hypoglycaemic episodes.

Depression is associated with poorer outcomes in diabetes control and evidence suggests that poor self-care in depression leads to poor glycaemic control, along with the increased use of health services.22,23 There is a threefold risk of mortality caused by depressive episodes in diabetes, which was demonstrated in a UK study.24 The Pathways study in the US showed a 1.67 and 2.3 fold increase in mortality.25 The US National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) compared people with diabetes and depression to people with diabetes without depression and non-diabetics, and showed a 2.5 fold increase in mortality over an eight year follow-up study. It has also been shown that people with depressive disorders have an increased risk of developing diabetes.4,26

Pathogenesis of depression-diabetes link

The psychological model

The psychological model has been the traditional explanation for the association between depression and diabetes in that the emotional and practical burden related to diabetes care leads to depression. In other words, the depression is caused by diabetes. This is however not supported by the literature.24,25 Also, at present there is very little evidence that only treating the depression will improve glycaemic control, although it does improve mood. There are arguments that the direction of association is reversed or

bidirectional.26,27Depression and insulin resistance

The diabetes spectrum ranges from insulin resistance to impaired glucose tolerance (frank diabetes) due to failure of secretion of insulin. Insulin resistance is defined as reduced sensitivity of receptors to the available insulin and it can be peripheral or central. Insulin resistance is a determinant in availability of free fatty acids in blood that are needed for tryptophan and serotonin concentration in the brain. Finnish, Dutch and Chinese studies showed a positive correlation between depression and insulin resistance.28,29,30 However, the major limitation to these studies was the utilisation of self-report depression which may have inadvertently classified symptoms of undiagnosed diabetes as depressive. A Japanese case-control study showed improvement in insulin resistance in depressed patients with antidepressant treatment.31

Depression and HPA axis

The stress response allows the body to deal with both environmental and psychological threats. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated by stress and this leads to a cascade of reactions that returns the body to a homeostatic state. First of all CRH (corticotropin releasing hormone) is released onto the pituitary receptors which leads to the secretion of corticotropin into plasma and ultimately results in cortisol secretion into the blood. This inhibits the gonadal, growth hormone and thyroid axes and at certain levels activates the inflammatory response. The HPA axis also activates the sympathetic nervous system, which increases catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), stimulates the immune response and increases cognitive functioning. The collective metabolic effects are gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis and insulin resistance.32 There is substantial evidence that cortisol and CRH are involved in depression as high levels of cortisol have been observed in depressed patients.33,34,35,36

Diabetes-depression link and the ANS

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems which function in opposition to each other to preserve the dynamic balance of the body’s vital functions. The sympathetic nervous system increases the heart rate, ventilation and causes dilatation of the bronchi. It releases adrenaline and noradrenaline. The parasympathetic system on the other hand slows the ventilatory rhythm and causes contraction of the bronchi using acetylcholine as its neurotransmitter. In stressful states, the HPA activates the SNS and causes the immediate anxiety response. Irregular sympathetic tone may result from excessive or persistent activation which in turn may lead to dysfunction in metabolic parameters.

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a measure of cardiac vagal tone and also serves as a sensitive indicator of how well the CNS controls the ANS. There is an established link between HRV and depression as decreased levels of HRV are known to be associated with depression.37,38,39 It has also been suggested that acute alterations in the cardiac autonomic tone may be responsible for the increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) events and mortality in patients with depression.40,41 However, it is yet to be clarified whether HRV can serve as a clinical predictor of worse depression. There may be a plausible link between depression and diabetes mediated through the ANS although very limited literature is available to support this.

Diabetes-depression link and innate inflammatory response

A biologically plausible hypothesis known as the ‘macrophage theory of depression’42 says that depression is associated with a cytokine-induced acute phase response. The latter is postulated in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and its associated clinical and biochemical features.43 The acute phase response leads to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines which are associated with pancreatic beta cells apoptosis, reduced insulin secretion and insulin resistance with onset of type 2 diabetes. There is growing evidence that stress and depression are associated with acute phase response.44

Genetics of the diabetes-depression link

There appears to be genetic traits in both type 2 diabetes and major depression which aggregate in families due to a complex interaction between the environment and genetic risk.45 To date, little research has been carried out to investigate the direct link between depression and diabetes. Due to the human genome sequencing project which has increased the understanding of patterns of sequence variation, it is now possible to carry out genome-wide surveys of common variant associations and to assess the combined genetic risk for common complex traits such as depression and diabetes.

Diabetes-depression link and birth weight

Since the unravelling of the foetal origins of adult disease in the early 1990s, there is some evidence to suggest a relationship between birth weight and type 2 diabetes later in life.46 There is some evidence, though weak, to suggest a link between low birth weight and depression in later life.47 It is however yet to be determined whether overweight babies have increased risk for depression.

Diabetes-depression link and early childhood adversity

While a systematic review was consistent for the adverse impact of the accumulation of negative socioeconomic status for CAD risk, same has not been found to be true for diabetes.48 An important factor for later life depression-diabetes comorbidity may be educational attainment in childhood.49 In a birth cohort study which was followed up to age 32 years, it was found that children who suffered maltreatment showed a significant and dose response increase in CRP levels by 80%, independent of health behaviours in adult life.50,51 Unfortunately, there are no studies to date which compare the risk factors for diabetes and depression over the life course in the same sample.

Diabetes-depression link and the role of antidepressants

Antidepressants have an important role in aiding the understanding of the pathogenesis of the depression-diabetes link. Anecdotal evidence and a small number of randomised controlled trials show that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have a hyperglycaemic effect, while selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), especially fluoxetine and sertraline, are anorectic, improve insulin sensitivity and reduce glucose levels. Partial evidence does exist that treatment of depression with antidepressants does improve insulin resistance and possibly weight loss.52,53,54 On the other hand, there is negative evidence from the US Diabetes Prevention Program for antidepressants.55 A small proportion of the sample self-reported use of antidepressants had a two to three-fold rise in diabetes risk in those randomised to placebo and to the lifestyle intervention. There was no observed increased risk in the metformin group with antidepressant.55. Antidepressants may also have an immunomodulating effect, which has been observed in animal models. This has a positive effect on glucose metabolism.56

Practical considerations

In a large meta-analysis conducted by Anderson et al, the prevalence of depression in people with diabetes was 11% while the prevalence of depression that was clinically relevant was 31%.57 Worldwide estimates of depression prevalence among people with diabetes vary by diabetes type and also in developed and developing countries.

There are many problems to be envisaged in dealing with patients with these two disorders. Some of these problems and their impact include the fact that depression and diabetes symptoms overlap, hence the patient and clinician may be unaware of depression and may primarily attribute the changed status to worsening diabetes self-care. Secondly, depression may be associated with onset or amplification of physical symptoms, in which case the patient may not sense that they are fully understood or supported by their clinician during healthcare visits when the physical or laboratory results do not correspond to subjective complaints. Thirdly, depression is commonly associated with difficulties with diabetes self-management and treatment adherence. The patient may feel resigned about their ability to make changes. For example, “I know what I’m supposed to do, but I keep doing the wrong things and I don’t know why”. The clinician on the other hand may feel discouraged about the ability of the patient to make the relevant changes in their care. Fourthly, individuals with depression may attempt to regulate emotions with food and substances, and the clinician is not able to understand the underlying depressive symptoms and the patient’s desperation to regulate emotional pain and may come across as judgmental.

Next is the problem of stressors that interfere with self-management strategies and worsen diabetes status which may also precipitate or exacerbate depression. These impact both on the patient and the clinician, who may attribute poor diabetes outcomes to a decrease in self-management because of a busy lifestyle but may not appreciate the insidious development of depression and its consequences. Next in line is the fact that depression may reduce the ability of affected individuals to trust others or to be satisfied with healthcare. Depression is commonly associated with changes in healthcare seeking patterns and following through with appointments. The patient may be reluctant to make appointments, show up for appointments, seek support or collaborate with healthcare providers during appointments. Another problem is that depression may be associated with poor blood glucose control irrespective of behavioural actions. This may lead to a decreased sense of control of illness and may influence the motivation of the patient to engage in further clinical treatment recommendations. Depression is also commonly associated with difficulty organising tasks, hence clinical instructions may need to be written, repeated and checked for comprehension while the patient is depressed. Also, depression leads to a more pessimistic view of the future. Thus, clinicians may need to help depressed patients to break down tasks into manageable action steps that may have shorter-term pay-off (for example, reduction of physical symptoms). Lastly, depression is commonly associated with anxiety. Clinicians therefore need to consider the presence of anxiety which heightens a patient’s uncertainty around decision-making and increases a general sense of dread about the likelihood of success.

Management guidelines

In a review, Gilbody et al58 found that screening for depression is effective only if aimed at finding patients with sufficient severity of depressive symptoms that warrant treatment and if the appropriate treatment is subsequently offered as a result of the outcome of the screening.

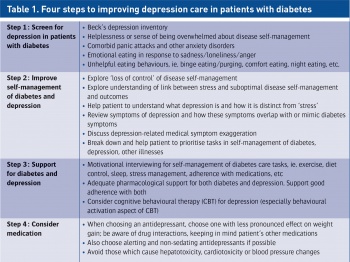

There are four steps in improving depression care in patients with diabetes (see Table 1).

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)