GENITO-URINARY MEDICINE

NEPHROLOGY

PHARMACOLOGY

Understanding urinary incontinence

With urinary incontinence it is important to devise treatment strategies in line with patient expectations and discuss surgical interventions if appropriate

January 8, 2015

-

The two functional roles of the bladder are storage and elimination of urine. Urinary incontinence (UI), the involuntary leakage of urine, remains undetected and undertreated worldwide despite its substantial impact on quality of life, including social, emotional and economic aspects.1

The two most common forms of incontinence are:

- Stress urinary incontinence (SUI), defined as any urine loss resulting from physical exertion such as jumping, running and coughing

- Urge urinary incontinence (UUI) related to overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) defined as urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with OAB-wet giving urinary incontinence, in the absence of urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology.2

While a specific aetiologic cause of urinary incontinence is often identifiable in younger patients, a multifactorial syndrome is more likely in older patients. In the older population, urinary incontinence may represent the intersection of neuro-urinary pathology, age-related factors, comorbid conditions, medications, and functional and cognitive impairments.

Ageing leads to many factors that predispose to urinary incontinence: detrusor overactivity, decreased bladder contractility, decreased flow rate, increased post void residual (PVR) volume, and change in diurnal fluid excretion. These factors do not necessarily result in urinary incontinence, and incontinence is not a part of ‘normal’ ageing.3

In the history it is important to:

- Elicit lower urinary tract symptoms such as frequency, urgency, nocturia and dysuria

- Check for risk factors such as obstetric history, vaginal deliveries or pelvic surgeries

- Attempt to differentiate stress from urge incontinence

- Rule out any reversible causes of urinary incontinence, any red flag symptoms and urinary tract infection (UTI).

A focused physical examination should be performed, tailored somewhat in each case, based on the specifics of the patient’s incontinence complaint and pertinent medical and surgical history.

The key components of the physical examination are similar for men and women, with a particular focus on the cardiovascular, neurologic, abdominal and pelvic/genital/digital rectal examinations. A cough stress test can be useful in visualising stress incontinence and urinalysis should be undertaken in all patients looking for signs of infection and haematuria.

If referred for specialist review, post-void residual urine volumes, uroflow tests and cystoscopy may be performed, and further imaging and urodynamics may be considered.

Prevalence/epidemiology

The precise prevalence of urinary incontinence is difficult to estimate as it is under-diagnosed and underreported. Most studies report some degree of UI in 25-45% of women.4 Age is the single largest risk factor for UI and reports of UI are as high as 84% in older people. Pregnancy, childbirth, diabetes and increased body mass index are associated with an increased risk of UI. Prevalence of UI in men is approximately half that in women, and surgery for prostate disease is associated with an increased risk.5

The prevalence of specific types of incontinence is difficult to estimate because of a wide variation in definitions. In general, about half of affected women have stress incontinence, with mixed stress and urge next most common, and urgency incontinence least common. These proportions change with age, with urgency incontinence becoming more common.1

Overactive bladder/urge urinary incontinence

The aetiology of OAB is unclear and indeed there may be multiple causes. It is often associated with overactivity of the detrusor muscle – a pattern of bladder muscle contraction observed during urodynamics.1

Initial treatment strategy should be conservative in the form of behavioural therapies. Fluid intake, weight loss, bladder retraining and physical activity advice should be given. A 25% decrease in fluid intake and its reduction during the hours before sleep promote significant improvement in urinary frequency, urgency and nocturia, and quality of life.3

Excessive caffeine intake is an independent risk factor for detrusor overactivity. Caffeine is present in coffee, black tea, cola soft drinks and chocolate. Carbonated drinks, citrus fruit, vinegar and alcohol are associated with increased urinary frequency and urgency. Avoiding excessive consumption of these elements is recommended.

Bladder training helps patients to regain control of the micturition reflex to eliminate the feeling of urgency and urge incontinence episodes. The initial interval between voiding is gradually increased so the patient reaches a comfortable interval of two to four hours between micturition episodes. Success rates are approximately 80% in the short term. Consequently, the Fifth International Consultation on Incontinence recommends bladder training as a firstline treatment for OAB.6

Pharmacological therapies

The lower urinary tract is controlled by neural input from autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and somatic (pudendal) nerves. Sympathetic nerves transmit information via alpha-adrenergic receptors in the urethra and beta-adrenergic receptors in the bladder, while parasympathetic and somatic nerves exert their effect via the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and activate nicotinic cholinergic receptors.7

If conservative measures alone are not effective, one should consider adding in pharmacological therapy. Anticholinergic drugs such as oxybutynin and tolterodine are the first choice in the pharmacological treatment of OAB and detrusor overactivity.7 The anticholinergics are effective in promoting improvement of symptoms and quality of life. Even with the emergence of more selective antimuscarinic drugs, new administration routes and formulations for single daily use, adherence to anticholinergic drugs remains low. This is mainly due to side-effects and/or poor clinical response. Dry mouth and constipation are the most common adverse effects, accounting for approximately 50% of the drop-out rate. Antimuscarinics are contraindicated in patients with urinary retention, gastric retention and uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma.2

More recently, beta-3 adrenergic agonists have been shown to be effective in the management of OAB and detrusor overactivity. They act by promoting relaxation of the detrusor muscle and increasing the bladder capacity without increasing the residual volume. The administration of 50-100mg mirabegron for 12 weeks significantly reduced the mean number of incontinence and voiding episodes in 24 hours. It has shown a more favourable side effect profile and comparable efficacy.2

Refractory OAB/UUI

Patients with persistent urgency incontinence symptoms despite an adequate trial of standard treatment (lifestyle changes, behavioural therapy and four to 12 weeks of pharmacotherapy) can be referred to a specialist, depending on the patient’s goals of care.

The specialist may consider the following: onabotulinumtoxin-A injections, neuromodulation and surgical interventions, such as augmentation cystoplasty, depending on availability of resources. Onabotulinumtoxin-A (injections into the detrusor muscle are conducted using a cystoscope) is recommended in refractory cases by the European Urological Association, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and the Fifth International Consultation on Incontinence.6 The risks of onabotulinumtoxin-A injection are urinary retention and an increase in UTIs.

Sacral nerve stimulation involves the placement of an electrode that passes a current through the S3 nerve root foramen and alters the neural signalling to the detrusor muscle so that urgency and frequency are reduced, after a test electrode for two weeks a permanent implant can be considered.

Augmentation cystoplasty is reserved for severe cases. This involves the grafting of an ileal patch into the bladder to increase capacity and decrease phasic contractions, but can result in retention, mucus production, stones and a potential risk of malignancy in the bladder after 10 years.

Stress UI

The diagnosis of stress urinary incontinence is made by a combination of history and urinary stress testing. Additional testing (PVR, cystoscopy, pad test) and urodynamic studies are useful when planning continence surgery.

The major cause of stress incontinence is urethral hypermobility due to impaired support from pelvic floor. A less common cause is an intrinsic sphincter deficiency, usually secondary to pelvic surgeries. In either case, urethral sphincter function is impaired, resulting in urine loss at lower than usual abdominal pressures.8

Initial management should start with lifestyle advice (weight loss, caffeine/fluid intake reduction, smoking cessation), physical therapies and scheduled voiding. Supervised pelvic floor muscle training or exercises should be offered as a first option for of SUI. Kegel exercises have been shown to improve the strength and tone of the muscles of the pelvic floor (ie. the levator ani and particularly the pubococcygeus) and benefit both men and women with stress or mixed type UI. Patients can perform pelvic floor muscle exercises by drawing in or lifting up the levator ani muscles, as if to control urination or defecation with minimal contraction of abdominal, buttock, or inner-thigh muscles.9 Vaginal cones and pessaries may be considered in treatment of SUI even without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse.2

Pharmacotherapy in SUI is not very common. In postmenopausal SUI topical oestrogen may be used as an adjunct to physical therapy and surgery. Initial conservative management should be attempted for eight to 12 weeks and thereafter the patient should be reassessed on success.4

When surgical intervention is being contemplated for SUI, NICE guidelines recommend urodynamic studies and multidisciplinary team discussion before proceeding to surgery. When urethral hypermobility is present, the surgical treatment options include retropubic suspension, bladder neck slings and synthetic midurethral sling (MUS). When intrinsic urethral deficiency is the primary cause, treatment options include periurethral or transurethral injection of bulking agents, bladder neck slings/retropubic MUS and artificial urinary sphincter (AUS).

Retropubic urethral slings are recommended as firstline surgical intervention for SUI. The options include transvaginal tape (TVT), transobturator tape (TOT) and now the single incision mini sling. The idea behind the transobturator procedure is that the placement of a tension free polypropylene tape reproduces the suburethral hammock like fascia as a support, preventing leakage. The most common intraoperative complications are bladder perforation (0.7-24%), haemorrhage and, more rarely, injuries to the obturator nerve, epigastric vessels and urethra. Postoperative complications include urinary retention, urinary tract infections, retropubic haematoma and, less commonly, vaginal wall erosion, de novo urinary urgency and vesicovaginal fistula.2

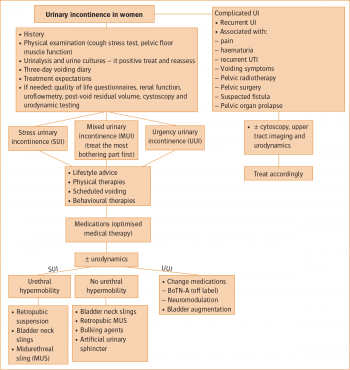

Figure 1: Management of urinary incontinence in women(click to enlarge)

Figure 1: Management of urinary incontinence in women(click to enlarge)

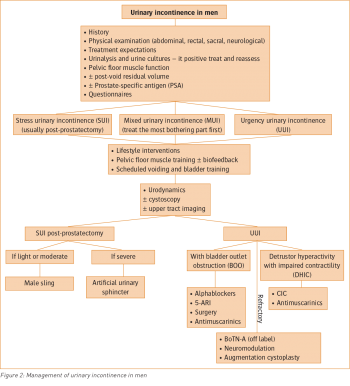

Figure 2: Management of urinary incontinence in men(click to enlarge)

Figure 2: Management of urinary incontinence in men(click to enlarge)